There’s a Chair in There – Determining Age through Materials and Typology

by Jessie Gray

The ladder back chair, an artefact from the Grainger museum, came with very little information about its history and materials. The 1909-1914 date given to the object relates to its acquisition by Rose Grainger, correlating to the period when she was living in London. The chair’s label may have offered more information but unfortunately it is scratched and not completely legible.

Conservation specialist Robin Hodgson examined the chair and assessed it as being made in England, due to the use of English oak in the manufacturing of the frame. She also gave a rough manufacture date of 1830’s, citing typology and material use. With further research, I was able to compile material and typological evidence that supported her view.

Typology

Typology

The chair is made in the Chippendale style, as evident in the curved cabriole style front legs and straight Marlborough back legs. It is likely that the piece’s dark finish was intended to emulate mahogany, a fashionable but expensive furniture material (New 1981, p. 60).

Research into English furniture typology has revealed that these features could indicate two broad dates of manufacture. The first from 1750 to 1830, which corresponds with the Chippendale era to the start of the Gothic Revivalist period (Cloag , p. 82, 95). The second possible period could be in the Antique Revivalism period, from the 1870’s to 1910 (Rivers & Umney 2003, p. 21).

However, the pad-foot design on the cabriole legs are more typical of the previous Queen Anne furniture, rather than the claw and ball design that featured heavily on Chippendale furniture. This blending of Chippendale and Queen Anne stylistic elements suggests an earlier manufacturing date.

Varnish

Varnish

Shellac varnish, which fluoresces a bright orange, was the most common English furniture varnish in the 17th century (Rivers & Umney 2003, p. 19).

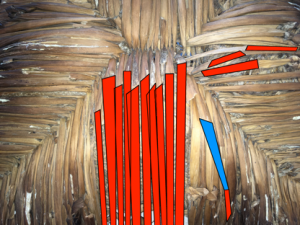

Woven seat material

The materials and technique of seat weaving is also suggestive of an earlier manufacturing date. This style of seating is hand-woven from rush, which is identifiable from its underside, where its natural form is visible (Baker 1979, p. 25). With the invention of the power loom in the 1850’s, rush woven seats became less common in favour of cane, suggesting an earlier date (Rivers & Umney 2003, p. 31).

Nails

The red corrosion suggests the nail is iron, and the rectangular shape of the nail is suggestive of iron nail typology ranging from 1805-1891. In addition, white corrosion product on the nail shows that the object was tin plated, another clue that suggests the chair was made before the mid 1850’s (Rivers & Umney 2003, p. 31).

Despite all this proof, material identification and typological evidence cannot give an exact date, but can only narrow it down to 1805-1830, the earlier of the two possible manufacturing dates.

The Tear in the Chair: Making Repairs

The most involved and time consuming stage in the treatment of Ladder Back Chair was the making and attaching of repairs.

The first step was to plan the repairs. As there was not enough space to attach them to the railing, I wasn’t able to repair every broken piece of rush. However, I decided to repair the top level of rush, as these would hold the rush below them in position.

The next stage in the repair process was the testing of adhesives and repair designs. Starch paste was chosen to adhere a layer of paper onto the chair railing, to which the Plextol® B500 repairs would be attached. Starch paste, as opposed to Plextol®, was also chosen to adhere paper tabs to the rush, as its adhesion is strong but not so strong as to pose a danger to the original material. Plextol’s® strong adhesive strength was used for structural repairs to the chair, and different concentrations of Plextol® were tested, along with designs for the repairs.

Once the testing stage was complete, the repairs needed to be made. The repairs were to be made from toned Japanese paper impregnated with starch paste to give them strength and similar physical properties to the rush.

The repairs were dried under weight on a curved base to simulate their final position on the rush.

When adhering the paper to the railing, some innovation was required to achieve an even pressure. This was done by laying bamboo skewers across the paper and placing small sandbag weights onto the skewers.

The repairs were adhered and weighted during the drying process. To protect the rush around the repairs, a layer of remay was placed on either side, followed by blotter on either side of the remay.

The paper repairs were being anchored to linen threads, which acted as a stabilization method to prevent the seat filling from falling through the hole left by the rush loss. This gave the repairs more structural integrity. Adjustments had to be made to the repair design when they were placed, as it was found that the thread was preventing the repair from lifting up to reach the rush.

Once the repairs had all been adhered, the final step in the treatment was aesthetic integration with the original material through inpainting. Acrylic paint was used to avoid solubilising the starch paste with water-based pigments. As the rush had a variety of colours, the initial colour match was performed to match the lightest colour in the rush. Once this was achieved, darker pigments could be added to vary the colour as needed. Each repair was painted with a variant of the base mix, and once the paint had dried, a light wash of darker pigment was painted over each of them to give a coherent appearance and to tone down the brightness of the paint. The final step was to add in some detailing with a darker paint to imitate the patterns on the rush.

The paper on the railing was left unpainted as it was a difficult location to apply paint to, and it wouldn’t be seen when the chair was upright.

Overall, this treatment was very effective. It was a lengthy and involved process, but has fulfilled the structural and cosmetic aims of the treatment to a high degree.

Beware the Chair: Preparation for transport, storage and display

The final step in the treatment process was to secure the chair for transportation, storage and display, and offer further recommendations to the custodians to ensure the long term safety of the object.

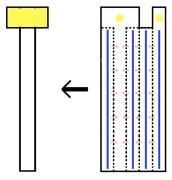

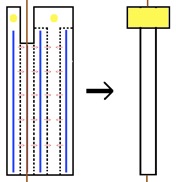

To prevent the loose rush cords on the top of the seat from moving around during transport, small stabilizing platforms were made from library board. These were designed to have a flat piece of library board about 1.5cm wide, to which smaller, U-shaped pieces of library board were adhered. These U-shaped pieces will cradle the rush cord, holding them in place and preventing distortion and friction.

When forming the U-shape, a brief survey of materials available in the lab showed that two dental picks had the exact circumference of the rush, making them the perfect tools to mould the library board around. However, it was found that they needed to be held in place and weighted down while they dried. To do this, bamboo skewers were placed on each of the supports and the skewers were weighted on either side with sandbags.

When finished, these were slid in underneath the loose rush and worked to hold them in place.

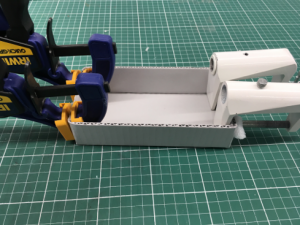

The next step was to make a box to house pieces of rush that were lost during treatment. The fragility of the rush meant that with the changes in physical positioning that were required for treatment, pieces of rush fell away before they could be consolidated. These were collected in a ziplock bag during treatment, but needed to be rehoused so that they could be safely transported and stored with the object to avoid disassociation.

The box was made to be as large as needed to hold the rush, to prevent it from taking up too much storage space. Space was left for a foam bed to be placed at the bottom. A label was then created to allow for easy identification of the material and the object it belongs to.

In preparation for storage and display, two sheets of Mylar were made to fit between the rush seat and the textile pillow. The first sheet is larger, offering greater protection from physical wear and intended for storage. The second is smaller, cut so that it is visually hidden beneath the pillow, and intended for display. The Mylar will also help prevent dust from settling into the rush cords.

The object was then secured for transport. Original transport materials were reused to avoid waste.

The last step in this treatment process was to formulate recommendations for the storage and display of the object. Being an object made from plant materials, there are particular environmental conditions that should be met, including keeping a stable RH and keeping the object in dry space with good air circulation.

One important factor that has to be considered, particularly relevant to furniture, is the threat posed by visitors. Often being unaware of the fragility of historical materials, visitors have been known to use furniture in museums and historic houses, leading to damage. Passive methods of indicating a chair is not to be used, such as placing a dried flower on the seat or a decorative rope over the armrests, could be considered. Place the chair behind a barrier or in a case, while less passive, are also viable options. These recommendations are communicated to the custodian in the official treatment report.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Grimwade Centre for Cultural Materials Conservation’s lecturers for providing support and advice on my treatment decisions. I would also like to thank The Grainger Museum for their trust and support.

References

Baker, C 1979, Chair Caning & Seat Weaving, Storey Publishing, Massachusetts.

Cloag, J 1934, English Furniture, AC Black, London.

New, S 1981, ‘The Use of Stain by Furniture Makers 1660-1850’, Furniture History, 17, pp. 51-60.

Rivers, S & Umney, N 2003, Conservation of Furniture, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.