Louise Lateau en Extase

By Alexandra Taylor

From the get-go this painting demanded rigorous, round-the-clock TLC. Equally as fascinating as the treatment was the narrative behind the work.

Part One: Treating Louise Lateau en Extase

Consolidation Sandwich

The condition of the work, according to Managing Conservation in Museums, was deemed to be in unacceptable. Upon seeing the painting for the first time, we determined that the following issues required some careful consideration.

- Active/inactive mould outbreaks across verso and recto

- Stretcher bars showed signs of bora infestation

- Severe abrasion to canvas recto had left paint friable and in need of consolidation

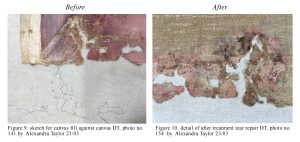

- Two major tears required repair and infilling/inpainting to retain areas of great significance: subject’s face and stigmatic hands

- Canvas loss at bottom edge needed a canvas fill

- There was significant paint loss across the entire recto

- Discolouration across 1/3 painting surface

- What looked to be a previous tear repair with wax resin needed to be removed

- Overall surface spotting/staining/dirt

The most immediate threats (mould and bora outbreaks) were eliminated quickly and sufficiently. During this, we were taken aback by the paint loss. Fortunately, we’d prepared for this and had lens tissue pockets in place around the most friable areas. However, the entire recto surface was very fragmentary and further damage seemed inevitable unless consolidation could take place.

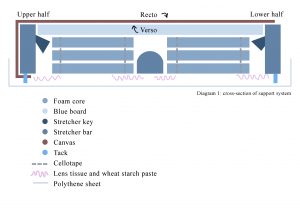

Before we could begin, it was necessary for the surface to be made planar. A custom-designed support system had to be inserted beneath the primary support. Our “sandwich” was created from a single layer of blue board with Mylar insert set up against the canvas verso and three layers of recycled foam core cut to shape around jutting keys, held together with cellotape. All material tailored to the exact height of the bars (200mm) fit within the stretcher frame. Japanese tissue bridges adhered from the stretcher bars to the makeshift support held everything in place. Once the wheat starch had set and the support seemed firm, we were able to flip Louise over so that the recto faced upwards, as indicated in the diagram below (note: not to scale).

Once the canvas was planar consolidation could begin. 5g Aquazol 200 resin in 22.5g deionised water and 22.5g isopropanol was prepared. In order for the application to be precise (leaving as little shiny residue on the paint surface as possible) we each chose to work with dental tools under the Grimwade Centre’s Möller-Wedel Stereo Microscope. 10% Aquazol 200 was wicked cleanly beneath the flaking paint, proving to have strong penetrative and adhesive qualities suitable for consolidation.

In the most friable areas the surface tension was reduced by applying 1:1 water to isopropanol. In this instance, a brush soaked the solution up whilst the dental tool took aim. The brush, hairs heavy with the mixture, was placed against the stem of the dental tool enabling the consolidant to dribble down the stem and into the shattered paint. Heat was sometimes applied with a hot spatula (40ºC) through silicone release film in order to plasticise both the Aquazol 200 and the paint layer. Different techniques had to be implemented in the most challenging area around the proper left arm, as demonstrated in the video below.

Video 1: consolidation DT, video no. 1 by Alexandra Taylor 09/03

Part Two: Filling Louise Lateau en Extase

Louise Now Filling Fine After Canvas Insert

As indicated in the diagram from Part 2 DT (see Image 3 and Diagram 1), very little canvas along the bottom remained tacked to the stretcher edge. Most of the canvas had fallen away, leaving a weak, open weave prone to further fraying and disintegration. We decided that a canvas fill was necessary to keep what remained intact.

The canvas chosen for fill had to not only mimic the weft and warp ratio of the original, but an equal total grams per square metre had to be met. We were specifically looking for a canvas of 270gsm, and Kim successfully managed to track down the only local store to stock it! Chapman and Bailey at 350 Johnston St, Abbotsford, housed the linen we needed, with an equal weft/weave count of 32 x 32 per 20mm2 and identical body to suit. Once the canvas had been wet out, re-stretched and dried, the filling process could then take place.

The shape of the original canvas was traced onto the new and the negative was cut out. Care had to be taken as the bottom edge needed to remain one piece of linen – one dud slip of the scissors was all it took to send us back to the drawing board. The pressure was on! Spot inserts for losses off the edge also had to be cut to shape, the smallest being roughly 2mm wide. When all sections were pieced together, 25g of pre-prepared Polyamide thread was used to adhere canvas together, as demonstrated in the video below. Heat was applied with a spatula set at 85ºC through silicone release film. This plasticised the adhesive and, once cool, resulted in a smooth adhesion.

Video 2: canvas fill tear repair DT, video no. 2 by Alexandra Taylor 23/03

Background: Investigating Louise Lateau en Extase

The Ecstatic Visions and Bleeding Skin of a Belgian Hysterical Woman

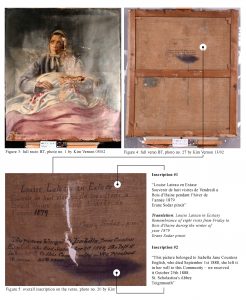

Louise Lateau en Extase by Franz (François) Sodar is the relic of an age where Victorian science clashed vociferously with spirituality. Lateau’s character came to symbolise “the marvellous”, exciting the sympathy of bystanders and igniting current debate around the laws of nature and religion.

According to the British Medical Journal (1871, p. 479) Lateau was ‘subject to much hardship in early life’, raised on a ‘plus que frugal’ diet with little to no education. Lateau was forced into taking charge of a crippled old woman from the tender age of eight and, during the 1866 cholera epidemic, spent her time nursing and burying its victims. Devout Lateau then, having impressed divine favour, supernaturally began to receive the stigmatic marks corresponding to those left on Christ’s body by the Crucifixion. The prominent Belgian physician Dr Lefebvre, Professor of General Pathology and Therapeutics at the University of Louvain, refined all aspects of the phenomenon that befell Lateau in his investigative study Life of Louise Lateau; her life, her ecstasies and her stigmata.

According to Lefebvre, the first sign appeared on the 24th of April 1868 as a large gushing cut on Lateau’s side. She sought the advice of a priest, ‘the director of her conscience’, who kindly reassured her and then ‘advised her not to speak of it’ (Lefebvre 1873, pp. 17, 24). Lateau suffered in silence until, on the 8th of May, other stigmatic marks materialised flowing ‘in quantity’ from her hands and feet (Lefebvre 1873, p. 24). Lefebvre (1873, p. 24) notes that the haemorrhages recurred ‘generally about noon’ every Friday and, despite wrapping the victim’s hands in leather gloves, nothing could be done to stop the bleeding. Lefebvre (British Medical Journal 1871, p. 479) confirmed how “otherworldly” these oozing wounds appeared under a microscope, ‘most had a triangular form, as if made by the bites of microscopic leeches’.

From the 17th of July onwards, the bleeding was accompanied by fits of ecstasy during which Lateau claimed to have distinct visions of the whole scene of the Crucifixion. This regular spectacle soon attracted the interest of other physicians and ecclesiastical authorities, as well as members of the general public who would flock en masse to assemble in front of the cottage. This crowd would have included our painter, Franz (François) Sodar, who painted Louise Lateau en Extase from the memories he had from his visit on the winter of 1879.

Although many people like Sodar and Lefebvre were convinced by this holy phenomenon, the British Medical Journal published an article in 1871 (just three years after the arrival of Lateau’s first holy lesion) that rallied against divine intervention, drawing upon the studies of Dr Henry Lee as proof of fraud. Instead of fastening a piece of easily perforated leather to Louise’s hands as Lefebvre had done, Dr Lee secured mittens of lead held together with a steady starch bandage. When the wrappings were removed upon his next visit, fresh wounds were revealed. Dr Lee held the lead to light and found it peppered with tiny holes ‘large enough to emit a needle’ (British Medical Journal 1871, p. 479). Thus, on the 13th of May 1868 Louise was discharged as an imposter. Following this, the British Medical Journal (1871, p. 479) sarcastically purposes ‘here we must irreverently suggest that [Lefebvre’s] microscopic leeches were probably needle-points’.

The British Medical Journal concludes its column with the following passage in reference to the twelve-year-old Welsh fasting girl Sarah Jacobs. As desperate as Lateau for fame and fortune, and with the encouragement of her parents, Jacobs starved herself to death in 1869.

‘Have we not lately displayed our love of the marvellous in the attention bestowed upon the Welsh fasting girl? And was not the investigation which resulted in her death by starvation, rendered most unnecessary by the conviction entertained by an ignorant and unreasoning multitude that the possibility of a human being living for several months without food or drink was a legitimate subject for inquiry? And now we are asked to believe that the ecstatic visions and bleeding skin of this Belgian hysterical woman there is something opposed to or above the ordinary laws of nature. We protest against such a conclusion, as calculated to bring disgrace upon science and discredit upon theology.’ (1871, pp. 479-480)

Acknowledgements

Firstly, I would to thank Ian Gourlay for his trust and support in deciding to share Louise Latau en Extase with The Grimwade Centre for Cultural Materials Conservation. I would also like to express immense appreciation for my treatment partner Kim Vernon, whose intuition and expansive material knowledge drove this project forwards. Finally I would like to acknowledge our supervisor Dr Nicole Tse for her immeasurable guidance throughout our conservation treatment.

References

- British Medical Journal 1871, ‘Ecstasy and Stigmatism’ in The British Medical Journal, Vol. 1, No. 540, May 6th 1871

- Keene, S. 1996, Managing Conservation in Museums, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford

- Lefebvre, F. 1873, Life of Louise Lateau; her life, her ecstasies and her stigmata, (Eds. Spencer Northcote J), London, Burns and Oates