A tool for celebration: Monash Archive Monash University (MAMU)

As part of practical conservation treatment and assessment subjects, students would like to share their work. There is a wide variety of approaches and artefacts being worked on.

This blog post expands upon the poster “Piasan rapa’i: A tool for celebration” presented by Rosie Cook at the 2016 International Conference and Cultural Event (ICCE) of Aceh in conjunction with the Music Archive at Monash University (MAMU):

The GCCMC had the opportunity to assess the condition of an Achenese rapa’i drum from the Music Archive at Monash University (MAMU), and to recommend how best to care for it. This project was an interesting opportunity to design an appropriate treatment that considers both the physical and intangible properties of a world culture musical instrument.

Drum before treatment, top and bottom view

Description

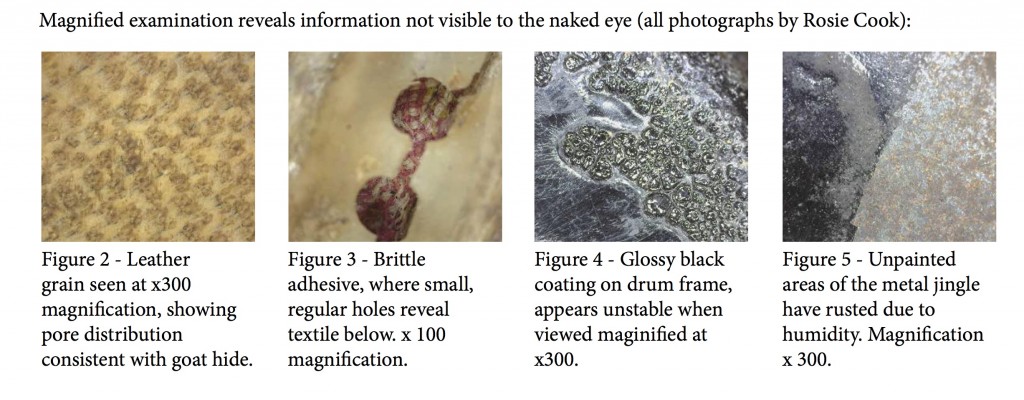

A large frame drum, 42cm in diameter and 10cm high, with a frame is made from a slice of hollowed out tree trunk, and is covered with a skin drumhead. Rapa’i drum frames are traditionally made from the wood of the jackfruit tree (Kartomi 2012), although it was not possible to confirm if this was the case, and the dark wood has a glossy coating. The drumhead is possibly rawhide as it does not appear to have been treated, and the grain is consistent with goat hide, a frequently used material for rapa’i (Kartomi 2012). A single hole in the side of the frame contains a pin securing two metal jingles and an loop of plastic cord, likely to have been used for hanging the drum when not in use. Inside the frame is a loop of rattan, known as a ratoh, which is used for tensioning the drumhead prior to playing (Kartomi 2012).

Condition

The drumhead is slack and appears to have lost some of its flexibility. Adhesive securing the rawhide to the edge of the frame has cracked and sheared away. The varnish on the frame is slightly powdery and shows signs of separating. The metal jingles are slightly rusty.

Ethical considerations of the treatment

This drum belongs to the rapa’i family of musical instruments, played by male musicians in both secular and religious performances in Aceh, where it is considered ‘a symbol of Acehnese unity and cultural identity’ (Kartomi 2012, p.318). Additionally, Acenese musical instruments are conceived and maintained with respect for the spirit of their original materials as well as of the finished instrument (Kartomi 2012). Consequently in order to respect its intangible values, consideration was given to the following ethical issues:

Is handling and treatment of this object by a female, non-Achenese/Muslim conservator appropriate and acceptable?

- Consultation with MAMU – no objection raised

- Literature suggests that women are generally not considered suited to play the rapa’i drums due to the physical strength required and the gendered division of roles and behavioural expectations (Kartomi 2012). However ‘the prophet reportedly allowed them to play frame drums’ (Kartomi 2012, p.319) and Acehnese culture celebrates many female heroes (Smith 1997)

- Respectful handling and reversible, non-invasive and sensitive treatment pursued

Can the drumhead be adequately re-tensioned and tuned according to the musician/maker’s original standards and intent (Odell and Karp 2005)?

- Research describes the process for tautening and tuning the drumheads using fire or moisture depending on atmospheric conditions (Kartomi 2012)

- In traditional practice, a rapa’i drum is ‘mystically potent object’ and its making requires ‘rare spiritual and practical skills’ (Kartomi 2012, p. 324)

- Information and skills are not available to the conservator to achieve this result; additionally the fragility of materials may result in damage to the instrument

- Re-tensioning and tuning of instrument was not pursued

Should the drum be re-tensioned if it is not going to be played?

- Research indicates the rattan hoop stored inside the drum frame is the ratoh, used to tauten the drumhead to tune it immediately prior to playing, and is afterwards removed to allow the skin to rest (Kartomi 2012, p. 324-325)

- Treatment was focused on an aesthetically appealing result without causing any changes to the object, in the event that at a later date it is possible for future custodians – preferably a rapa’i musician/maker with the appropriate skills – to re-tension the drumhead using traditional methods and materials (Appelbaum 2007, p. 70)

Treatment

Step 1 – Dry cleaning

- Gentle dry cleaning with a soft brush and vacuum is only method suitable given the slightly friable coating on the frame of the drum, and the extreme vulnerability to water of the untreated hide (Barclay 2005; Barclay and Hellwig 2005)

Step 2 – De-watering of metal jingle

- Jingle composition was not identified beyond the presence of a reddish corrosion product on the strongly magnetic metal. Literature suggests copper (Kartomi 2012, p. 331) however colour of metal and corrosion products does not support this

- Use of ethanol not recommended due to black paint marks on the surface of the jingle discs which could be solubilised during cleaning process (Ashley-Smith 1987); micro-crystalline wax coating used instead to seal and protect surface from further corrosion (Cassar and Barclay 2005)

- Renaissance Wax applied with gloved finger to each of the sides of the two jingles (four sides total). After initial application, buffed with soft cloth and then repeated for a second application

- Circular insert made of Remay placed between the two metal discs to encourage air circulation and prevent micro-climate which could foster further corrosion (Rivers and Umney 2003)

Step 3 – Creation of custom support to re-tension skin

- Re-tensioning skin through humidification is inappropriate as untreated skin is very susceptible to moisture (Barclay and Hellwig 2005)

- Design of support system that will improve visual appearance of drum skin without requiring treatment (Barclay 2005)

- Circular insert made of polyethylene foam cut to dimension of drum skin inner surface distributes the pressure of a circular custom pillow designed to fit inside drum

- Weight of drum is now slightly supported by the skin of the drum resting on hidden inner cushion, which assists in smoothing out surface and reducing buckled appearance. Cushion can also be adjusted to allow drum to be displayed at an angle if desirable

Drum after treatment, without insert (left) and with insert (right).

Recommendations

- Custom-made support will allow the drum to be displayed with slightly tensioned skin, however it is not recommended to leave on support whilst in storage as effect of gravity may cause further deformation (Barclay 2005)

- Handle with care and avoid using abrasive material to dust frame as coating is friable (Barclay 2005)

- Given composite nature of the drum including metal components, ideal environment must be dry enough so that corrosion does not take place, but not so dry that the wood cracks or warps. Relative humidity (RH) of around 35% will stabilise most corrosion products without damaging the wood; the hide of the drumhead is very susceptible to moisture and must be stored below 50% RH (Barclay and Hellwig 2005)

References

Appelbaum, B 2007, Conservation Methodology, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

Ashley-Smith, J (ed) 1987, Science for conservators Vol 2: Cleaning, The Conservation Unit Museums and Galleries Commission, London.

Barclay, RL 2005, ‘General care of musical instrument collections’, in Barclay, R, ed. The care of historic musical instruments, CIMCIM, electronic edition, <http://network.icom.museum/cimcim/resources/the-care-of-historic-musical-instruments-full-text/>, accessed 30 March 2016.

Barclay, RL and Hellwig, F 2005, ‘Materials’, in Barclay, R, ed. The care of historic musical instruments, CIMCIM, electronic edition, <http://network.icom.museum/cimcim/resources/the-care-of-historic-musical-instruments-full-text/>, accessed 30 March 2016.

Barclay, RL and Karp, C 2005, ‘Basic conservation treatments’, in Barclay, R, ed. The care of historic musical instruments, CIMCIM, electronic edition, <http://network.icom.museum/cimcim/resources/the-care-of-historic-musical-instruments-full-text/>, accessed 30 March 2016.

Cassar, M and Barclay, RL 2005, ‘Instruments in their environment’, in Barclay, R, ed. The care of historic musical instruments, CIMCIM, electronic edition, <http://network.icom.museum/cimcim/resources/the-care-of-historic-musical-instruments-full-text/>, accessed 30 March 2016.

Kartomi, M 2012, Musical journeys in Sumatra, University of Illinois Press, Urbana, Chicago and Springfield.

Odell, JS and Karp, C 2005, ‘Ethics and the use of instruments’, in Barclay, R, ed. The care of historic musical instruments, CIMCIM, electronic edition, <http://network.icom.museum/cimcim/resources/the-care-of-historic-musical-instruments-full-text/>, accessed 30 March 2016.

Rivers, S and Umney, N 2003, Conservation of furniture, Butterworth‐Heinemann, Oxford.

Smith, HS 1997, Aceh art and culture, Oxford University Press, Kuala Lumpur.