Chance and fortune: gaming in France

More than merely children’s toys, playing cards have a long and fascinating history. In printmaking, they represent some of the earliest examples of the media as they were first hand-made in Europe in the 15th century (see Printing 1450-1520). They were typically printed from woodcut on a large sheet, with a patterned backing glued to the verso, and would later be cut into individual cards. Additionally, they show the technical development of the art through the application of colour with stencil.

Surprisingly, they also convey a world of information about art and society, and are a record of social exchange. Their designs hold many messages and can often be traced to a specific time and location. Playing card games transcended social classes as they were played by aristocrats and peasants alike. They have the power to evoke strong emotions via the thrall of the game and the consequences of chance and fortune. As material objects, cards record insights about human interaction and moments in history: they could be exchanged, written on and their meanings transformed.

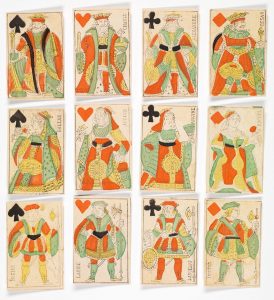

A set of 32 piquet cards has been added to the Baillieu Library Print Collection. Piquet is a trick-taking game rather like euchre which uses 32 cards instead of the regular 52 deck. The set of cards was acquired to provide students of printmaking studies a practical example of the use and application of colour with stencil, but they are also of interest to students of history and psychology.

France has an important role in the development of playing cards and their suits of trèfles (clovers or clubs), carreaux (tiles or diamonds), cœurs (hearts) and piques (pikes or spades) were adopted by many other nations. Originally these suits symbolised positions of the church, later they represented roles at the royal court.

Face cards were often associated with a particular person; the queen of spades for example, has long been viewed as Joan of Arc, and sometimes these court cards were named. In the game piquet, the face cards became known identities from history and literature. The rois (kings) were: David, Charles, Ceasar and Alexander, the dames (queens): Pallas, Judith, Rachel and Argine, and the valets (jacks): Hogier, LaHire, Hector and Lancelot. [1.]

In the 18th century the French Revolution saw the royal family beheaded, and likewise their portraits were removed and banned. The playing cards produced after the Revolution had to be stripped of allusions to the former monarchy. In 1808 Napoleon also decided to replace the court cards with a new design. He commissioned the painter Jacques-Louis David to design a deck in which the figures displayed neoclassical elegance. However, a similar design by the medallist Nicolas Marie Gatteaux was instead selected, and this corrected version included the names of each figure on the card. [2.]

In 1813 Gatteaux rethought the design and produced another deck, and this time the face cards returned to a more traditional Paris pattern which can be seen in the Baillieu’s deck of cards. Gatteaux’s design had a brief life before it too was replaced by the double-headed face cards, typically seen on playing cards today.

Kerrianne Stone (Curator, Prints)

References

[1.] Catherine Perry Hargrave, A history of playing cards and a bibliography of cards and gaming, New York Dover Publications 1966, pp.31-57

[2.] Prototype for a set of Imperial playing cards

Leave a Reply