The company of the Hanged Man

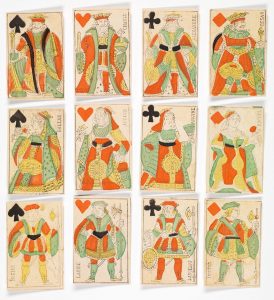

It is widely accepted that Tarot cards developed in Italy in the 15th century. They sprang out of the playing card tradition and the first engraved images, known as the Tarocci, were initially attributed to the Renaissance master Andrea Mantegna. However, the artists of these first tarot are unknown, and following their first appearance, further artists quickly began to create new versions of this appealing game.

Tarot imagery was a reflection of human experience, or a journey of the soul, and it is not until the 18th century that the cards became the tools for fortune-telling and occultism.

Included within the deck are the Major Arcana or trump cards, and these picture cards are the recognisable archetypes. After tarots became standardised, these 22 cards were numbered, so that number 12 becomes the Hanged Man. This is not an auspicious card to draw, for he represents betrayal and is a symbol for the traitor. He is depicted hanging by one foot from the gallows, as traitors in Renaissance Italy were likewise branded. [1.] This shady character, and his companion, have now infiltrated into the Baillieu Library Print Collection.

Like many printed cards, this is a hand-crafted woodcut and the colour has been applied with a brush and stencil, yet there is something about this subject that appears even more unsettling to the viewer. It is that this Hanged Man has been inverted; he is hanging the wrong way around. The Hanged Man is the subject of much speculation by occultists, and this inversion invites even more conjecture. Auguring aside, it is the chief clue which allows this card to be traced to the Belgian Tarot.

Before arriving in Belgium, the Tarot was introduced to the French at the conquest of Milan and Piedmont in 1499. This encounter produced the Tarot of Marseilles, a term which refers to tarots produced in Marseilles and which are recognisable by their standard pattern. The history and linage of a symbol may be complex, as in the case of the Belgian Hanged Man, which appears to derive from Jacques Viéville’s version of the Tarot of Marseilles; a pack with a dubious heritage. It is likely that Viéville (a pseudonym) copied this set from a sheet of printed cards, as the authorities would plane the images off woodblocks to prevent smuggling and tax evasion on the cards, and thus the images in this deck are in reverse. [2.] The rather obscure Belgian paper trader Pierre-Antoine Keusters would have seen this version when he produced a similar deck containing these two cards.

In the company of the Hanged Man is card number 13, or Death, a symbol which requires no explanation. This fearful card, again imaged backwards, has also entered the collection.

With an innocent beginning, the Tarot altered its imagery and its eerie meanings through the passage of time. With the arrival at the Belgian Tarot and its somewhat disreputable heritage, we find a pack of rouges, as much as a transfixing work of art.

Kerrianne Stone (Curator, Prints)

References

[1.] Ronald Decker, A wicked pack of cards: the origins of the occult tarot by Ronald Decker, Thierry Depaulis, and Michael Dummett, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996. p.45