NEW PROJECT | Buruli ulcer

Words and photo: Jason Axford

On 26 April at the Peter Doherty Institute, Federal Minister for Health, Greg Hunt, announced new NHMRC funding to investigate the mysterious and rather horrific disease commonly known as Buruli ulcer (BU) (formerly known as Bairnsdale ulcer).

The project is led by Prof. Tim Stinear in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity at the University of Melbourne. Over the next two years, a team of interdisciplinary experts will work on filling gaps in the science surrounding BU. PEARG are pleased to be one of the ten groups working together on the problem. We are tasked with understanding the role of mosquitoes in the transmission of this disease.

BU is a neglected tropical disease, with most cases occurring in rural sub-Saharan West African communities. It is named after a county of Uganda. BU starts out as a painless area of swelling, like a mosquito bite but without the itchiness, typically developing into a skin lesion months. The infection is treated with strong antibiotics once detected, however, serious ulcerations may require surgery, even whole limb amputation. In Australia, the disease rarely leads to amputation as we have ready access to modern medical facilities. The lesion is caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans which produces a necrotising, immunosuppressive cytotoxin called mycolactone. The genus Mycobacterium contains the etiological agents of tuberculosis and leprosy. Much like those awful diseases, BU is a slow-growing pathogen, making epidemiological investigations difficult as the delay between infection and diagnosis obscures how and when the patient came into contact with the bacteria.

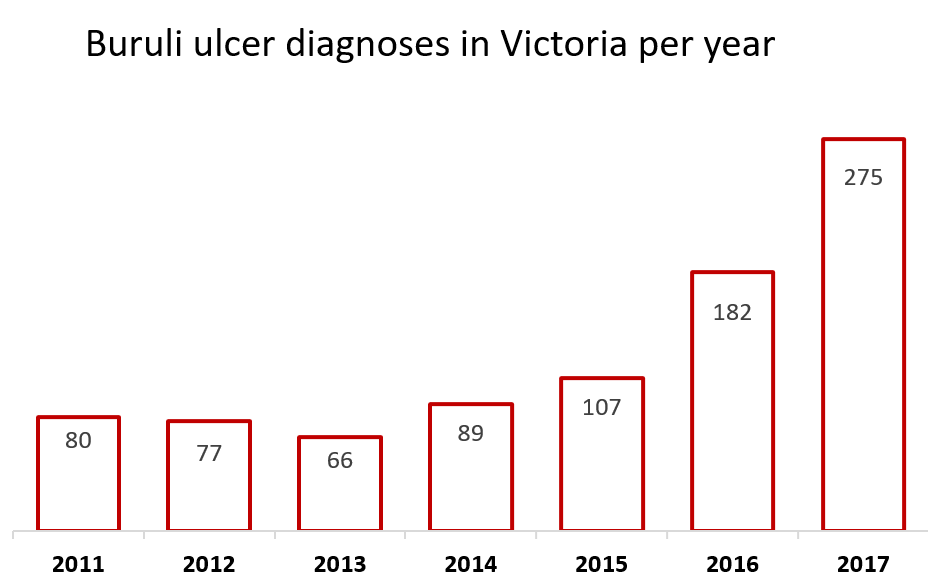

There is an urgent need to research due to an alarming surge in cases around the Bellarine and Mornington Peninsulas. In Victoria there has been an almost doubling of cases from year to year since 2015 and is expected to continue for decades. Controlling this disease will safeguard the health and wellbeing of people in these areas as well as protect the tourism industries relied upon by the local economies. Furthermore, generating spatial risk models will also benefit many African communities where epidemiological studies are too challenging to conduct due to a lack of reliable local data, expertise and funding.

Data source: Department of Health and Human Services

Data source: Department of Health and Human Services

Because BU cases are geographically associated with water bodies and most infections occur on the hands and feet, mosquitoes have been long suspected as vectors. Previous research supports the idea that skin trauma on contaminated surfaces, possibly via mosquito bite, mechanically introduces the pathogen. Our lab has generated pilot evidence supporting this hypothesis, however, further research is required1. Possums are natural reservoirs of M. ulcerans and a positive association exists between those carrying it and human cases of BU. Five mosquito species have been detected carrying M. ulcerans in Victoria, the most common of these along the Mornington Peninsula being Aedes notoscriptus (pictured in main title). A. notoscriptus feed on humans and other animals, including possums, making BU a zoonotic disease and mosquitoes the prime suspects moving the infection from possums to humans. It is notoriously difficult to rear A. notoscriptus in a laboratory environment, but we are up to the challenge of getting a locally-sourced colony going. Our background in Wolbachia research for controlling arboviral disease transmission is perfectly suited for studying this complex biotic interaction. We will perform the research necessary to inform control strategies being planned and implemented over the next two years and beyond.

Why BU is occurring in geographically restricted areas round Port Phillip is a mystery at this stage. Because the distribution of mosquitoes and possums is wider than BU cases, other environmental factors may be important. This new project will determine other factors at play to generate spatial risk mapping tools which can direct control strategies to break transmission cycles. The evidence we will generate feeds directly into these tools so that decisions can be made based on reliable, high quality science.

Control strategies will aim to reduce mosquito populations in a focused and directed manner. The removal of breeding sites in residential properties is one such measure that has been employed with other mosquito borne diseases. Reducing the incidence of M. ulcerans in possums is another possibility. More traditional control strategies such as fogging with aerosolised insecticides may have unintended consequences such as selecting for pesticide-resistant mosquitoes and collateral impacts on ecologically important insects. We may be able to eschew fogging if sufficient data are generated to drive alternative approaches in disrupting the BU transmission cycle.

The next two years will be an exciting adventure as we explore the unknowns of BU. Keep an eye out for our findings on this blog for updates. This research will have a direct impact on how health authorities go about tackling BU and we are optimistic that increased understanding of the problem will save a lot of people from suffering a terrible disease.

1Wallace, J. R., et al. (2017). “Mycobacterium ulcerans low infectious dose and mechanical transmission support insect bites and puncturing injuries in the spread of Buruli ulcer.” Plos Neglected Tropical Diseases 11(4).