An intellectual legacy

The University’s Baillieu Library is turning 60, and fast adapting to the digital world.

By Anders Furze (MJourn 2016)

Most people who have studied at Parkville have a Baillieu Library story. From one student meeting her future husband across a communal study table to the political firebrand etching graffiti onto the leg of a study carrel, this one building has both hosted and encouraged human curiosity for 60 years.

“It’s stood the test of time,” senior librarian Karen Kealy says of the Baillieu. “It’s adapted quite well to the changing needs of the community.”

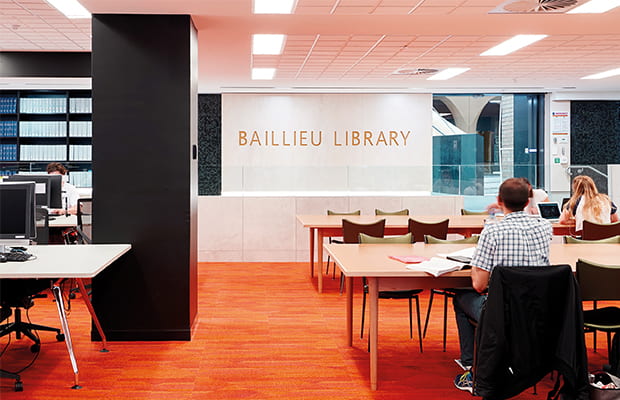

One small example of that adaptation can be found in the Robin Boyd-designed tables introduced into the building in 2015. Originally created as dining tables, the library sought permission from the Boyd Foundation to expand the original designs to provide enough space for laptops and books, with added power points placed discreetly underneath the tabletops.

“They’re beautiful pieces of furniture,” Kealy says of the tables and the accompanying Featherston Mitzi chairs, another mid-century design icon that has featured in the Baillieu since its foundation. “I often get approached by architects and designers asking if we’re ever going to sell them. And I say, ‘No, we’re just going to keep refurbishing them!’ ”

Prime Minister Robert Menzies opened the Baillieu Library in 1959. It was the University’s first permanent library and remains its biggest. Plans had been in the works for years, but World War II and a lack of money stalled progress, before a £105,000 donation from the Baillieu family changed everything.

“It was the first purpose-built library built after World War II,” says Kealy, who is Associate Director, Information Services and Library Spaces. “It was a pretty amazing thing to have achieved back in the 1950s.”

John F D Scarborough, who helped design parts of Scotch College and other university libraries, and who taught at the University, designed the building. Although elements have expanded and been refurbished, much of the original design remains.

“All the builders who come in, comment on the design,” Kealy says. “That original structure and design has enabled us to do those things quite well.”

The Baillieu might be a specialist arts and humanities library, but its prime position in the centre of the Parkville campus, and its large size, means it attracts students from all faculties. It’s easily the most popular of the University’s libraries, attracting about 100,000 visitors a year.

It’s not just students using it either. Alumni and members of the public are regularly welcomed into the building, and there’s even an alumni library membership available, which gives access to ejournals and book borrowing privileges.

“We get people coming in who might want to get stuck into the archives,” Kealy says. “We get lots of requests from families who might say, ‘My grandmother wrote a thesis, can I come in and have a look?’ ”

The Baillieu Library in 2019, where Robin Boyd-designed tables, which have been expanded to accommodate laptops and books, sit alongside reupholstered Featherston Mitzi chairs, another mid-century style icon.

All up, there are around 4 million volumes across the University’s collections, with the Baillieu housing the biggest print-based collection. But, in 2019, are people still borrowing books?

“Our loans figures have reduced over time,” Kealy admits. “But because of the nature of the collection, people are still borrowing, particularly our postgraduate students.”

Still, there’s no denying that times are changing. Some 85 per cent of the library’s annual materials budget is now spent on online resources, including ebooks, software and journal access.

But then, there has always been more to the library than books. Indeed, the sheer scale of what’s on offer is mind-boggling. There is study, research and IT support on hand, archives and even a gallery, expanded in 2014 thanks to a bequest from alumna Noel Shaw.

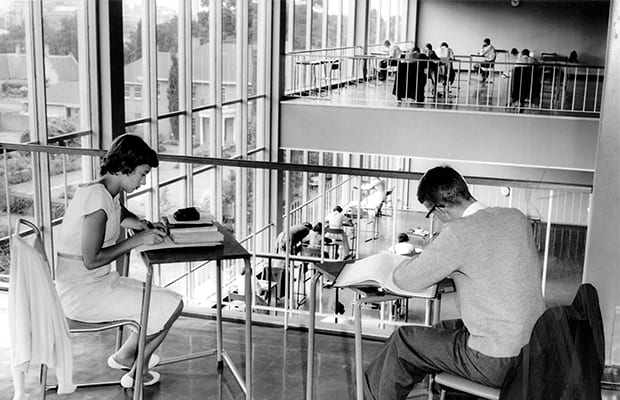

A report written for the 1959 University Gazette notes that, “During First Term practically every seat has been occupied for the greater part of the day.” It could have been written last week: space for students has been a perennial problem. The library has increased student seat numbers from 1340 in 2012, to 1878 last year.

Although students can access so many resources at home, many are still choosing to visit the Baillieu to access the internet, get advice on studying, take workshops and browse the collections. Taking their Featherston seats at their Boyd tables, they engage with each other, and the University’s intellectual legacy, in the process.

“The Baillieu is not just a study hall,” Kealy says. “We’re a library!”