Body of evidence

BY LIZ PORTER

Beyond comprehension: Tourists take in the scene at Kuta Beach in 2002. Picture: Getty Images

October, 2002: Clad in a heavy plastic apron and gumboots, Dr Pamela Craig is part of an Australian Federal Police forensic team working in the mortuary of Denpasar’s Sanglah Hospital. The forensic odontologist is examining, charting and X-raying the teeth of victims of the terrorist bombing of two Kuta Beach nightclubs, an atrocity that killed 202 people.

It is hot and exhausting work, but less emotionally draining than the alternative: working in the hospital’s “reconciliation room”. There she would be matching these charts and X-rays with the dental records of Australians missing since the bomb blasts. She would be looking at the victims’ photographs and personal details – and thinking of their families.

The non-expert might assume that working in the mortuary is the most confronting aspect of her work, especially when victims’ bodies are decomposing or bear the signs of violent death. But clinical examination allows Craig (BDSc 1966, MDSc 1973, GDipForenOdon 1991) to focus on the abstract details of anatomy. Her expertise in this area is important because body parts are all that remain of some victims. It is their photographs and personal belongings, the trappings of their individual humanity, that she finds most confronting.

Thirteen years on, the details of her final case in that 10-day tour of duty in Bali stay with her. The only examinable part of this victim was a small part of his upper jawbone.

“There was almost nothing to go on, except a knowledge of anatomy,” recalls Craig, still an honorary lecturer in oral anatomy and radiology at the Melbourne Dental School.

Studying an X-ray of the victim’s maxilla, the front part of his upper jawbone, she noticed the roots of the teeth were growing outwards, in a V-shape, with a wide gap in between – suggesting a tooth had once been there.

Trawling through the dental records of the missing, she came across a 21-year-old man from Perth who, at the age of nine, had an extra tooth extracted from between his two central incisors. But first she had to wait for the dental records to be flown in from Perth. When the X-rays arrived on Craig’s last day, they confirmed that the victim was that man.

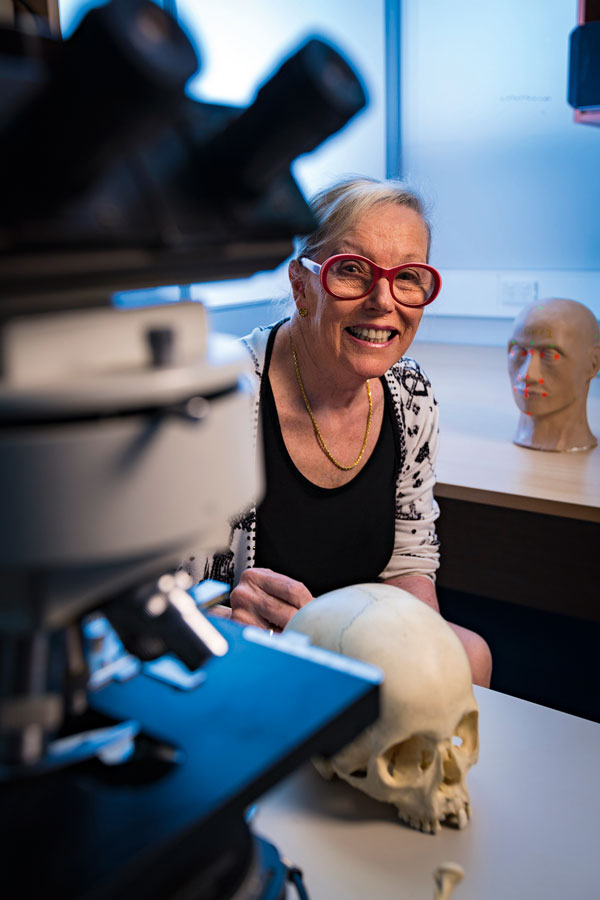

Dr Pamela Craig has worked on enough cases to make several seasons of a CSI-style TV series. Picture: Chris Hopkins

Craig has worked on enough cases to make several seasons of a CSI-style TV series, including one horrific Queensland murder in which a man with protruding teeth was accused of strangling and murdering 17-month-old Deidre Kennedy, whose body was found with bite marks.

Talking about that case remains a painful experience for Craig. While the details of the crime were horrific enough, she then faced an aggressive defence barrister while giving evidence in court – the kind of experience that persuades some forensic scientists to add a law degree to their qualifications.

Other cases have been less confronting. In 2007 she was consulted by a Singaporean businessman concerned about the authenticity of a tooth, supposedly one of the Buddha’s molars, just installed as the centrepiece of a new and expensive Buddha Tooth Relic Temple. This time nobody argued with her expert opinion: the tooth belonged to a cow or a water buffalo.

As a research partner to forensic Egytpologist Dr Janet Davey, Craig has also worked on some of the oldest “cold cases” imaginable. In one, she examined scans of the teeth of a child mummy from Egypt’s Graeco-Roman period. She concluded that the child had died as the result of septicaemia after an orthodontic procedure in which teeth were removed from an overcrowded mouth.

She has also spent more than 20 years as a part-time consultant in insurance and worker’s compensation cases.

Yet this impressive career in forensics was never part of Craig’s life plan. In fact, she believes if she had graduated in an atmosphere of equal opportunity she would have become an oral surgeon.

Enrolling in dentistry in 1962, she heard comments such as “it’s a scandal, training a girl’’… “she’s taking the place of a man” … “she’ll never work (as a dentist)”. Worse followed when she enrolled for postgraduate study.

“Nobody would give me a place in the graduate surgery program because I was a woman,” she says. “The only thing I was offered was paediatric dentistry because that was ‘suitable for women’.”

Then in 1974, while a registrar, she was offered a place in the PhD program. When she divulged that she was pregnant, the offer was withdrawn.

“It was the most rotten time,” says Craig. Forced to build a new life, she started part-time in a clinical practice in Camberwell, continuing there until 2005 when her wrist “wore out” and needed reconstruction.

By 1989 she was a mother of two, busy combining the Camberwell work with sessional university teaching, but hankering for an intellectual challenge.

Then she heard news that would change her life. University of London forensic specialist Dr John Clement was joining the Melbourne Dental School and starting a forensic odontology diploma. “He was barely off the plane when I was on the phone to him,” recalls Craig.

By 1993 she was a permanent part-time lecturer in anatomy and radiology and, along with fellow forensic odontologist Tony Hill (GDipForenOdon 1991) who died in 2013, working as a consultant to the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine.

It is Craig’s work in the highly specialised area of disaster victim identification that has made her reputation as one of Australia’s top forensic scientists. On Boxing Day 2004, when news broke that a tsunami had devastated coastal areas of South East Asia from Thailand to Sri Lanka, she was among the first to be called by the Australian Federal Police. She subsequently served four stints with the Thai-based multinational team of forensic scientists.

In 2009 Craig worked on identifying victims of a different kind of disaster: Victoria’s Black Saturday bushfires. Fortunately for the identification effort, most victims had been to the dentist and none of the local dental surgeries had been burnt out. This identification process offered its own unique difficulties, including “comingled” skeletal remains, with some people dying huddled together with their pet animals.

The process of identifying victims will always be harrowing for the forensic specialists involved, says Craig. But, as she discovered in her first case, in 1991, there is a satisfaction in being able to offer relatives an end to the terrible uncertainty about the fate of a loved one.

In that case, involving a jawbone found on Cape Woolamai beach, Craig worked with Tony Hill to establish that it belonged to a local youth who had been washed out to sea while surfing nearly a decade earlier. No dental X-rays were available. The scientists had only a school photo, in which the boy wore a blue-checked shirt, to guide them.

Using the checks as a scale, they were able to enlarge the photo to life size. They then superimposed a photo of the jaw bone, lining it up with the chin cleft, teeth

and bite line, as seen in the photo. The forensic scientists never met the boy’s family. But they received a message of thanks from them, via the police. “It gave them closure,” says Craig. “After that they were able to have a funeral.”

While outsiders often dwell on the confronting nature of forensic work, Craig points to the positives. Death, for example, holds fewer fears for her.

“Having seen so much death I have a more practical attitude toward it than most people, in that I accept it as an inevitability at the end of life,” she says. She also believes her work has given her an increased appreciation of the sheer delight of human existence.

“I know that one has a very tenuous hold on this mortal coil and it takes very little to push us over. It makes me think that life is very precious. So I am more careful and safety conscious perhaps than I should be.”

Craig also talks of the need to keep an emotional distance from her work.

“You have to build a wall and become dissociated from it, “ she says. “But it gets you in the end.” Yet, if there is another mass disaster in coming years, she will get the call. And she will go.