Decoding the Everest of scripts

Five questions for Dr Brent Davis, Archaeologist

By Lani Thorpe

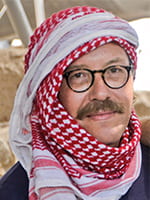

Dr Brent David is a lecturer in Archaeology and Ancient Egyptian in the Faculty of Arts’ School of Historical Land Philosophical Studies.

In the 1950s, great progress was made in the field of undeciphered scripts when English architect Michael Ventris deciphered the ancient Mycenaean Greek script Linear B. But its parent system, the Minoan script Linear A, remains famously undeciphered. Archaeologist Dr Brent Davis (PhD 2011) has devoted his career to its study, winning the Michael Ventris Award for Mycenaean Studies earlier this year in recognition of his work on undeciphered Aegean scripts.

Dr Brent Davis is a lecturer in Archaeology and Ancient Egyptian in the Faculty of Arts’ School of Historical and Philosophical Studies. His background is in both archaeology and linguistics, and his interests include the ancient cultures of the eastern Mediterranean and their languages and scripts.

1. What is an undeciphered script?

It’s a script we can’t read. Or, if we can read it, we can’t understand it. There are around 20–25 different undeciphered scripts around the world, some of them much more important than others. Decipherment of Linear A has always been one of the holy grails of archaeology, because the Minoan civilisation was so important, especially as a background for the Greek civilisation.

The Minoans were a Bronze Age civilisation that lived on Crete. They used Linear A on ritual objects and deposited them by the hundreds at Minoan outdoor shrines, so we have a lot of things like offering bowls with Linear A inscriptions around them. The sentences are very similar to each other but they’re never exactly alike, so by comparing them all to each other you can tell quite a lot about the language behind the script.

The Greeks, when they arrived on Crete in the Late Bronze Age, borrowed the writing system of the Minoans to write in Greek. We call this customised version of Linear A ‘Linear B’, and this script was deciphered in the 1950s by Michel Ventris. Because we know what sound values the various signs have in Linear B, we can actually pronounce Linear A words, but they’re gibberish, because they’re in a language we don’t recognise.

2. Why does deciphering Linear A matter?

As I tell my students all the time, archaeology is not about the stuff that you find, archaeology is about the people behind the stuff. That’s the only reason for digging it up – to try to understand more about them. And what better way of understanding a people than to be able to read their records in their own voice? Deciphering Linear A would be enlightening, as it would tell us things about the Minoans we might not have any other way of finding out. That’s the value of it, it’s a direct pathway into these ancient peoples’ brains. Awesome.

When the Greeks arrived on Crete, they absorbed a heck of a lot of Minoan culture and religion, so the Minoans have coloured Western civilisation. But we can’t read their records. It’s just like before we could read Egyptian hieroglyphs. People made guesses, but 95 per cent of them were wrong about what the Egyptians were trying to say with their writings. Once we could read hieroglyphs, then we could hear the Egyptians talking in their own language, in their own voices.

3. How does one get into the business of decipherment?

My father was a meteorologist, but he’d always dreamed of being a history teacher. It was never to be, but he had this wonderful set of bookshelves crammed with ancient history books, and even as a seven-year-old I’d look through them and just absolutely fell in love with archaeology.

I got my undergraduate degree in Linguistics at Stanford, and then for many years after that I worked in IT, helping to write the programmers’ manuals for the original Macintosh, back when Apple was just a small company. I continued in IT for a while, but I was unsatisfied. I’d just fallen into it, it wasn’t something I’d intended to do. What I loved was languages and archaeology, so eventually I decided just to quit, go back to school and do something I really loved. That’s when I came to the University of Melbourne to do my PhD, which I did on Linear A.

I had first read about Linear A when I was about 18, and thought, wouldn’t that be wonderful to study? Years later it turned out my PhD supervisor here in Melbourne was a specialist on the Minoans, so she greatly influenced my choices. The first great key to deciphering a script is to figure out which language it’s encoding. Until you know that, you’re kind of adrift. This is where the background in linguistics comes in. Being able to devise ways of looking at the script and comparing various sentences and intuiting things about the language behind the script – that’s very valuable stuff, because we’ll someday get a critical mass of those clues and we’ll hopefully be able to identify what the language is. That’s half the battle right there.

4. How niche is this line of work?

We specialists in undeciphered Aegean scripts are an international group of people, but a small one. I would say there are probably eight to 10 people around the world who are serious scholars of these scripts.

It’s a very close club and we all know each other very well.

One of the things that really marked Michael Ventris’s approach to the decipherment of Linear B was his willingness to share anything he found with everybody; he was completely open. That has become a great tradition now in Aegean scripts, and it’s definitely something we’re proud of. Anytime anyone discovers something new, they share it with everyone, because we need to work together on this, it’s not a one-person job.

We email each other a lot. I’m involved in a collaboration right now on Cretan Hieroglyphic, which was a precursor to Linear A, and someone else is working on a Cypriot script called Cypro-Minoan, which (like Linear B) was based on Linear A.

Those are the three main undeciphered Aegean scripts: Linear A, Cretan Hieroglyphic and Cypro-Minoan. I actually work on all of them, though all of us tend to specialise in one.

5. What are the chances of deciphering Linear A?

When Michael Ventris deciphered Linear B, he had texts that amounted to a total of about 20,000 signs. That’s only about three times the length of this article, if you were to type it out. It’s not a lot. But that’s kind of a critical mass – you have to have that much material in order to decipher a script without a bilingual. The Rosetta Stone is a great example of a bilingual: you’ve got Egyptian and Greek inscriptions, and they both say the same thing. You can read one of them, so you can intuit a lot about the other. We don’t have a bilingual for Linear A, and when you don’t have that, you need at least 20,000 signs of the script. Right now, we have about 8000 signs of Linear A, altogether.

But more is found every year. There has been one great Linear A archive in the past that’s responsible for the majority of the signs we have. So, if someone were to find another archive, the total number of signs could go up substantially. They’re excavating all the time in Crete; new Minoan palaces continue to be found, and palaces are where archives tend to be, so hope isn’t lost.

To decipher any script, you have to keep your mind open and you have to go over and over and over it. That’s how Ventris deciphered Linear B. He worked on it for ages, and then there came a day when he realised, this is Greek! Before that, he’d been absolutely certain it was Etruscan or some other ancient language. Once he’d correctly identified the language as Greek, though, his successful decipherment of the script was just a matter of time.