Medical fields

Sports medicine has come a long way from the days of the gnarled trainer with a slimy, wet towel and a few choice words of encouragement. By Peter Hanlon.

Kangaroos star forward Ben Brown is treated for concussion during an AFL match in 2017. PICTURE: FAIRFAX/AAP/JULIAN SMITH

Peter Brukner chuckles at the memory of the sports medicine landscape in the early days of his 47-year association with University Blues, when he was playing in the 1970s.

Now, Dr Brukner runs the Blues’ medical department of two doctors, four physiotherapists and eight physio students, who augment their studies working as trainers. Then, it was rather more primitive.

“We had a St John’s Ambulance guy, and if you got hurt and saw him running towards you, you got up straight away and pretended you were all right,” recalls Brukner OAM (MB BS 1977, Ormond College). “When you had a cramp he had this rope he used to put around your calf … God, he did some weird things.”

As in all aspects of the game, amateur football’s maturity when it comes to sports medicine is merely a reflection of life at the top. Sport and science have never been more entwined as the appetite to improve prevention, treatment and recovery becomes ever more ravenous. When Brukner and colleague Karim Khan (BMedSc 1982, MB BS 1984, PhD 1998, Ormond College) collaborated in 1993 to write Clinical Sports Medicine, which came to be regarded as the field’s bible, each chapter was appended with two or three references. “In the latest edition,” Brukner says, “every chapter has 200 to 300 references.”

The boom in research and knowledge has spawned an industry. Brukner’s first job at AFL level was as

Melbourne’s club doctor in the late 1980s. He’d do a full day’s work at his Olympic Park clinic, head down Punt Road to the Junction Oval and treat footballers who’d arrive for training from their day jobs or university studies. “It was Tuesday and Thursday nights from 5 to 8pm, then Saturday at two o’clock.”

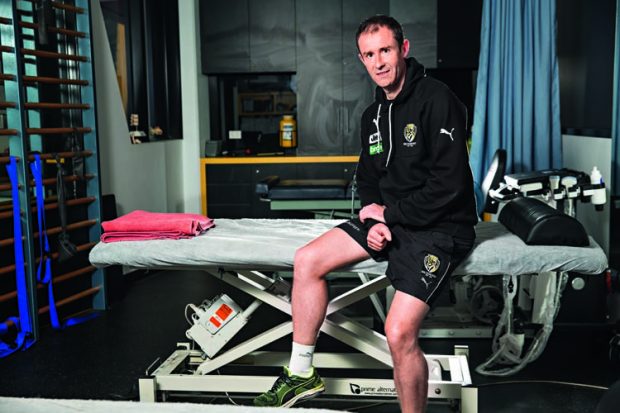

Doctors, physiotherapists, dieticians, massage therapists and sports scientists have become a team within every elite sports team. Richmond Football Club physio Anthony Schache (BPhysio 1994, PhD 2003) started with the Tigers in 2000, and rates the cohesion among the club’s medical and high performance professionals – and, crucially, their intersection with the football department – among the most enjoyable aspects of the job. He agrees with Brukner that prevention has been the area of the biggest advancements.

“When I started at Richmond the mentality was do everything we can to get as many players on the track for the next training session,” Schache says. “There was no, ‘How about we back off , try to manage this guy’s condition and work through a plan to build his load up and get him back playing pain-free?’ You’d do whatever Band-Aid stuff you could to get him out there, and worry about the next session when you got to it.”

Exercises specifically geared towards prevention have become the bedrock of individual programs. Hayden Morris, who was schooled by the “godfather” of knee surgery, John Bartlett, would love to see every child at Auskick or netball’s NetSetGo learning an exercise routine aimed at reducing the prospect of injury. But as someone who performs around 250 anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions every year, he acknowledges that ruptured knees are simply a fact of sporting life.

“Australians play a lot of sports, and we play dangerous sports,” says Morris (MB BS 1983). “We play Australian

Rules football, netball, soccer, basketball, rugby, we ski. These are all very high risk.”

Knees are the Everest of sporting injuries. Treatment a few decades ago involved major, open surgery that left tram track scars and stiffness, and often led to arthritis. “A lot of those people are coming back to see me now and having knee replacements,” Morris adds.