The Essay: Signs of hope on the road to Paris

Don Henry

BY PROFESSOR DON HENRY, PUBLIC POLICY FELLOW AT THE MELBOURNE SUSTAINABLE SOCIETY INSTITUTE

In November last year the leaders of the United States and China made what may well be a truly historic statement. Releasing the US-China Joint Announcement on Climate Change, President Barack Obama and President Xi Jinping committed to work together, and with other countries, to “adopt a protocol, another legal instrument or an agreed outcome with legal force” at the United Nations Climate Conference in Paris later this year.

The announcement went on: “They are committed to reaching an ambitious 2015 agreement that reflects the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, in light of different national circumstances.”

Whether or not the leaders of the world’s largest economies, and the two largest greenhouse gas-emitting nations, provided the leadership needed for a new global agreement to limit global warming will largely depend on negotiations in Paris in the first two weeks of December.

What are these negotiations about? What are some of the key elements under discussion? And what are the prospects of success?

In May the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change finalised a Synthesis Report of their latest findings for all governments. Written by more than 800 scientists from 80 countries, and based on an assessment of over 30,000 scientific papers, the report tells policymakers what the scientific community knows about the scientific basis of climate change, its impacts and future risks, and options for adaptation and mitigation.

The key findings are:

■ Human influence on the climate system is clear;

■ The more we disrupt our climate, the more we risk severe, pervasive and irreversible impacts; and

■ We have the means to limit climate change and build a more prosperous, sustainable future.

It is one thing for governments to accept the urgency of reducing greenhouse emissions, but the challenge has been in getting them to agree on a way forward. The Paris negotiations are occurring under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, first adopted in 1992.

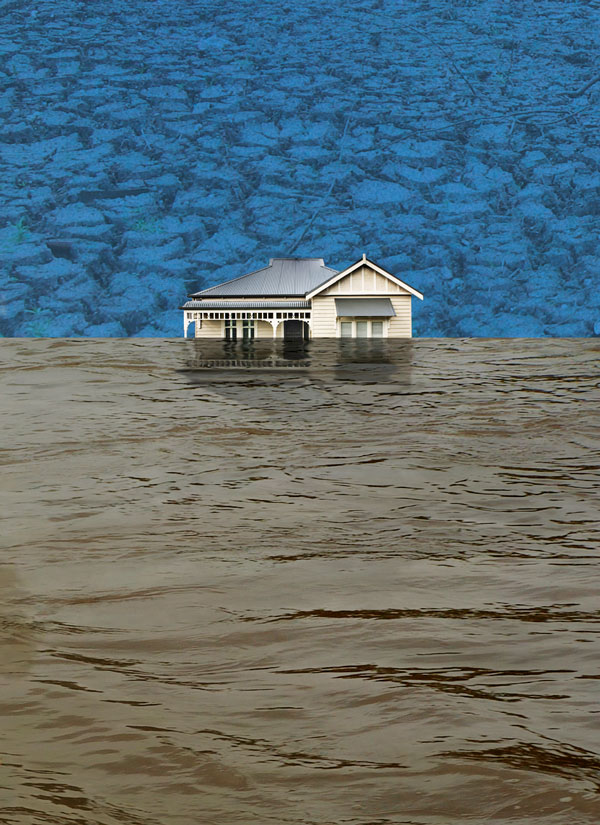

Illustration: Judy Green

Of course, many countries now have policies to limit emissions and to stimulate renewable energy. However, because emissions from any one country affect the climate of us all, global action is required. Two years of intense negotiations have delivered a draft text for the Paris negotiations. Each country is now putting forward indicative commitments of their proposed emission reductions and actions.

Significantly, November’s US-China announcement included targets. The US intends to achieve an economy-wide emission reduction of 26 to 28 per cent below its 2005 level by 2025. It agreed to make “best efforts” to reduce its emissions by 28 per cent. China expects its CO2 emissions to peak about 2030 and undertook to make “best efforts” to peak earlier. It intends to increase the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to about 20 per cent by 2030. In the announcement both sides intend to continue to work to “increase ambition over time”. Overall, governments have now agreed to the goal of keeping warming below an additional 2 degrees on pre-industrial temperatures to try to avoid the most dangerous impacts of climate change.

Some of the outstanding issues in the negotiations include what additional actions to reduce emissions can be encouraged if the sum of the national commitments does not adequately close the gap on what is needed to keep warming below that 2-degree goal. The important role that cities and state governments around the world can play in addition to the efforts of national governments is another focus of discussion to assist with this challenge. There is also considerable debate about whether there should be a goal for decarbonising economies around the world. A recent meeting in Germany of the major industrialised countries that form the G7 built momentum for this. At the conclusion, German Chancellor Angela Merkel said the meeting had agreed on the goal to “decarbonise the global economy in the course of this century”.

Experience in Germany, California, and more recently in China, shows that economic prosperity can be decoupled from growth in emissions and pollution. In essence, cleaner and more efficient economies can continue to deliver growing economic benefits while cutting emissions.

Another key element of the Paris negotiations is how to ensure sufficient funding is available to help vulnerable countries adapt to some of the damaging impacts already locked into climate systems. The effects of increasing storm intensity because of warming oceans and sea level rise associated with this are already being felt in many tropical island nations, including Australia’s Pacific Island neighbours, the Philippines, Indonesia, and south-east Asia.

Related to this is the need to scale up and encourage private-sector investment in cleaner technologies. A recent commitment by the Indian Prime Minister to substantially boost his country’s renewable energy is most encouraging, but highlights the need for a rapid increase in private-sector investment.

With the costs of renewable energy dropping rapidly – in particular solar and wind – a transformation of energy systems in many parts of the world is now occurring. Globally the level of investment in new renewable energy projects has now exceeded investments in new fossil fuel projects in energy generation. So what is the relevance of the Paris negotiations to Australia and the Asia-Pacific region? People across the region, including in Australia, support action on climate change and cutting emissions. Policy settings vary across governments, but in most countries in the region there is an increasingly rapid uptake of renewable energy and a mix of policies is being put in place to start the job of cutting emissions.

For example, in Australia more than one in seven households has rooftop solar panels. Bangladesh has the highest rate of solar installation in the region, while China and more recently India are dramatically scaling up manufacturing and use of renewable energy. China is on track to introduce legal restrictions on emissions and an emissions trading scheme next year.

The position that Australia takes into the Paris negotiations is significant. At preliminary negotiations in Bonn in June, China pointed out to the assembled nations that Australia had received more questions than any other country on its commitment to cut emissions.

Interestingly, international negotiations are now demonstrating that there are two strong drivers of change. One is the need to reduce emissions because of the damaging impact on climate; the other is the opportunity to develop new pathways to economic prosperity and well-being based on highly efficient and cleaner economies.

The continuing work of universities around the world, including the University of Melbourne, is important to the Paris outcomes and their implementation. The disciplines of climate science, engineering and technological development, the social sciences with their understandings

of human behaviour, political science and international affairs, climate policies, law and international governance, economics and business, are all informing decision-making and action.

What are the prospects of success at Paris? Because the negotiations follow the United Nations consensus approach they can be fraught. Finding common ground among so many countries and competing interests is always difficult.

But the leadership of the US and China is highly significant and has built momentum for an agreement at Paris. In their joint announcement, the leaders said the intent of their countries was to build the impetus for a successful agreement.

“The United States and China hope that by announcing these targets now, they can inject momentum into the global climate negotiations and inspire other countries to join in coming forward with ambitious actions as soon as possible,” they said.

Apart from any agreement, the current focus on climate change action around the world is creating the opportunity for the development and deployment of innovative technologies, continued public education, the advancement of science, and implementation of new policies, all of which are delivering significant advances for societies everywhere.

The key question remains, can our agreements and actions globally and nationally meet the great challenge of the urgency of emission reductions and the development of cleaner economies that our scientific community is so clearly pointing us towards?

A substantial portion of the greenhouse gases being emitted are long-lived in the atmosphere. Action today to bring down emissions is urgent. We have seen many years of very slow progress on global action to tackle climate change.

The compelling nature of the science and the great opportunities for economic prosperity and jobs growth through new cleaner economies should encourage every nation to strive for success at Paris.

Professor Don Henry is a Public Policy Fellow for Environmentalism at the Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute. He was formerly Chief Executive Officer of the Australian Conservation Foundation.