Inside Sarajevo’s Tunnel of Hope

I’ve spent the past month in Bosnia, researching how the war of 1992-1995 is remembered in public places such as museums and memorials. While in many locations throughout the country it remains difficult to remember the war, including the experiences of children, in Sarajevo there are many museums addressing the recent past. One of the more popular tourist attractions is the Tunnel of Hope, on the outskirts of Sarajevo. This museum marks the place where many people began their journeys out of Sarajevo to new countries.

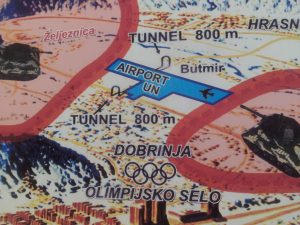

When war broke out in Sarajevo in April 1992, it was not long before the city was surrounded in nearly all directions. This map offers a stark illustration of the situation:

Only two months after the siege started, the commercial food market was totally depleted with people relying on cooking wild plants such as dandelions and nettles. Statistics provided by UNICEF to the UNHCR in June 1992 show that 80% of the population had only infrequent access to water and 20% had no access at all to water or electricity. These conditions only worsened throughout the siege and until its end in 1995, as the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia summarised, “there was no safe place in Sarajevo; one could be killed or injured anywhere and anytime”.

In 1993, the situation was so dire that the army resorted to building a tunnel, which became known as the Tunnel of Hope (or Tunnel of Life). Construction of the tunnel began on 28 January 1993, with groups of volunteers digging from two neighbourhoods: Dobrinja and Butmir. The two groups first touched hands on 30 July 1993, somewhere under Sarajevo airport, which was at that time controlled by the United Nations.

Throughout the remaining months of the siege, the tunnel allowed humanitarian supplies and army personnel in to Sarajevo. For many civilians the tunnel was the place that marked their departure from Sarajevo and their move towards other countries as refugees. It’s highly likely that some of the people who came to Australia from Sarajevo as refugees, particularly in the final years of the war, would have come through this tunnel.

Edis and Bajro Kolar, under whose house the Butmir entrance to the tunnel was built, estimate the daily average of people going through the tunnel at 4,000. This figure would include a very high percentage of military personnel and people delivering aid, so it’s not known exactly how many civilians left Sarajevo, and then Bosnia, through this tunnel. However, for those who did leave this way there’s no question that it was a last resort.

Video footage at the museum shows how uncomfortable the walk through the tunnel was. It was 800 metres long and around 1.5 metres high, so most people had to stoop. It was also prone to flooding, which was risky given the electrical wires running along the tunnel, and the lack of air circulation was another big problem. Today only a small section of the tunnel is available to tourists, due to safety concerns about the rest of the tunnel.

The museum, like the tunnel itself, has the continued support of the Kolar family whose house concealed the Butmir entrance to the tunnel. In the museum’s video footage, you can watch one of the Kolars handing people cups of water as they emerged from the tunnel. While the museum highlights the contribution of the Kolar family, visitors are not told of the Kolars’ motivations for enabling the tunnel. Why that house, out of the many in Butmir? Why that family? The Serbian army knew of the tunnel, but couldn’t find its entrances, so instead shelled the general area. You can still see the damage on the house, which is now the front of the museum.

This relatively small museum seems to capture so many aspects of the siege in one place: the struggle to get food and humanitarian supplies to the city; the desperation of civilians trying to leave; the UN in the middle, watching from Sarajevo airport. For those trying to understand the anguish of the siege and the determination of those who lived through it, the Tunnel of Hope provides a good starting point.

Recent Comments