The Sky is the Limit…ation

by Madeleine Ewing

Part I: First Impressions Last

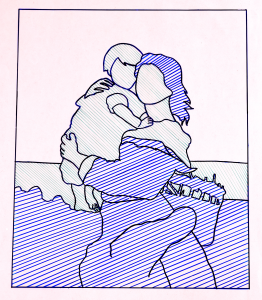

Welcome to the online conservation treatment diary for the portrait Untitled (Woman and Child). The aim of this blog is to provide an accessible platform through which each stage of the conservation process may be documented and reflected upon. Content will include pre-treatment, during-treatment and post-treatment updates in order to capture real-time problem solving and progress.

So, let’s get started!

Very little is known about the history of Untitled (Woman and Child). It’s currently part of the private teaching collection at the Grimwade Centre for Cultural Materials Conservation and was acquired as an academic donation. The painting has been treated by student conservators at least twice before myself and its condition is fair overall. Other than the losses along three separate tear repairs, the paint layer is stable and the strainer is structurally sound.

However, part of being a good conservator is accepting that looks can be deceiving – every object has hidden truths we must uncover through close scrutiny and scientific examination. Even so, first impressions are important and the objectives for my treatment pathway were clear from the outset. My primary focus will be to restore aesthetic integrity and legibility through the removal of the heavily discoloured varnish layer. The varnish has yellowed significantly and has completely changed the colour of the sky from a bright blue to a blotchy, muddy tobacco-yellow. This can be seen in the above detail where the rebate edge in the top-left corner shows the original blue sky.

After reading through the treatment report from a previous student, I was intimidated by the length and detail of the solubility testing section. Dozens of solutions, including some from Chris Stavroudis’ Modular Cleaning Program (MCP), failed to remove the discoloured varnish. I am lucky enough, however, to have a supervisor who recently conducted further tests on Untitled (Woman and Child) with some success. The painting appears to have two separate coatings – an overlying synthetic resin and an underlying natural resin. My cleaning program will therefore be carried out in two phases, addressing each layer separately. A series of free-solvent mixtures as well as Richard Wolbers’ solvent gels and emulsions will all be tested to find the most appropriate cleaning agent for each material.

The restoration of artist intent is a primary concern for conservators, and the prospect of being able to complete the treatment of a painting that has proved to be so challenging is an exciting one. There are, however, many ethical considerations bound up in the process of cleaning. At one level, it requires the permanent removal of original material. Some view the surface layer, deteriorated or otherwise, as a material accumulation of an object’s age and lifespan – its complete removal would result in the obliteration of the object’s lived history. There is no doubt a conflict between historical integrity and legibility at play here. In this case, I believe the extent to which the discoloured obscures the underlying paint layer justifies its removal and I look forward to finding a safe way of restoring the artist’s original intent in the coming weeks.

Part II: Solubility Issues

As student conservators, we’re always told to expect the unexpected. Having a contingency plan is often the key to success. As we will see, the treatment program so far has certainly proved this to be true.

After a series of chemical spot tests, the synthetic varnish layer appeared to have solubility parameters similar to that of Paraloid® B72 – an acrylic resin commonly used as a protective coating in painting conservation from the mid-late twentieth century. The most effective cleaning agent for safe removal was xylene in free-solvent form and at full concentration. This made me apprehensive at first. Xylene is a highly volatile and toxic solvent, so extra precautions were taken to ensure health and safety measures were met. Nitrile gloves and a filtering facepiece respirator were worn at all times. All treatment at this stage was also carried out in the fumehood to minimise petrochemical exposure.

Removal of the synthetic layer can be seen through increased fluorescence in the above images. The process was more time consuming than I expected. The amount of mechanical removal required with cotton swabs was also surprising. There was a ‘scratchy’ feeling to the surface underneath that is typical of high molecular weight copolymers like Paraloid® B72. As I was working in the fumehood, the painting had to be viewed in natural light at regular intervals to observe an increase in matte-appearance and confirm effective removal. Unfortunately, the xylene appears to have penetrated through the canvas and partially solubilised the BEVA® 371 film tear repair patches on the back of the painting.

Finding the right cleaning agent for the discoloured varnish has become quite disheartening. We are currently five weeks (over halfway) into our allocated treatment time and I’m yet to find an appropriate solution for the sky and ocean areas. Free-solvent mixtures, Wolbers solvent gels, emulsion gels and ‘Pickering’ emulsion gels have all been tested – but to no avail.

However, as seen above, I have had some success in cleaning the figures and foreground. I’ve created an emulsion using one of Richard Wolbers’ aqueous stock solutions with xanthan gum and benzyl alcohol. The gel was applied to the surface with a white-fibred synthetic brush for three minutes before being wiped away with a dry cotton swab. The recipe is as follows:

Stock Solution ‘F’

100ml (deionised water)

0.5g Disodium EDTA (chelator)

0.5g Boric acid

Adjusted to pH of 8.0 with 1M NaOH solution

Diluted to conductivity of 1000µS/cm

Emulsion Gel

50g of 2% w/v xanthan gum in deionised water

25ml of Solution ‘F’ (above)

10% benzyl alcohol

There are many benefits of using a gelled solution like this. For one, increasing the viscosity also increases the working time. It also restricts the physical penetration of solvent gels into painted surfaces. As gels require smaller amounts of solvent, they are much safer for both the conservator and the environment – an added bonus.

However, each pigment has unique properties and can interact with the same solvent in different ways. This was observed during treatment in areas containing reds and browns. These areas were much more sensitive, so both the solvent concentration and gel application times were adjusted accordingly. In the overlay below, green areas were cleaned with a xanthan emulsion gel containing 10% benzyl alcohol for three minutes, whereas blue areas were cleaned with the same gel base containing 2% benzyl alcohol for one-and-a-half minutes.

Neither of these solutions – or any others tested – was successful in removing the discoloured layer from the sky and ocean areas. Higher concentrations of benzyl alcohol in gel form posed serious risk to the underlying paint, where a significant amount of pigment transfer was observed during chemical spot tests. This prompted further scientific examination and investigation. Microscopic analysis into the surface topography of these areas can be seen below.

These protrusions are characteristic of metal soap aggregation – a degradation process caused by the interaction between lead or zinc based pigments and free-fatty acids in an oil-binding medium. XRF and FTIR-ATR analysis confirmed the presence of lead and saponification, respectively. When metal soaps form on the surface of a painting, they can crystallise and form dark crusts that cannot be removed with solvents. This may explain why the discoloured layer on Untitled (Woman and Child) has been unresponsive to cleaning agents tested throughout this treatment.

Due to time constraints, I have ultimately decided to cease solubility testing and move on to the structural reinforcement stage. This was a hard decision to make as removing the discoloured varnish was my primary objective, the effects of which are most noticeable in areas left unclean. Conservators of portrait paintings in the past have been condemned for the cardinal sin of over-cleaning faces and neglecting other areas. Although, I think it would be unethical to continue testing at this stage due to the extremely thin nature of the paint layer. Further materials characterisation using polished cross sections and GC-MS are needed to remove the discoloured layer in a safer and more accurately informed way. These are well outside the time constraints of this treatment, but could be an interesting research project for a future student conservator.

Part III: Final Thoughts

My treatment program continued with structurally reinforcing the primary support through strip lining. I’ll admit that removing a canvas from its original frame after nearly two hundred years was a daunting task. Even though the copper tacks were very small and corroded, they were removed quite easily.

Once the canvas was strip lined with BEVA® 371 film, new linen and reattached to the strainer, I began the final stages of aesthetic integration. I decided to fill areas of loss along the tear repairs with gesso. While we have access to more modern acrylic fillers, I felt that gesso would be the most compatible with original materials and sourced a traditional recipe of rabbit-skin glue and chalk whiting.

Once the fills were levelled and toned, the painting was revarnished for protection and proper colour saturation. A 20% solution of Laropal® A 81 in white spirits was chosen for its low molecular weight, aesthetic properties and safe reversibility. The brush-applied varnish, however, completely penetrated the paint and ground layers, again solubilizing the BEVA® 371 tear repair patches on the reverse of the painting. While these are easily replaced, it makes clear the thin nature of the paint and primary support, as well as the porous nature of the ground. Further unnecessary exposure to chemical solvents would be increasingly dangerous. I think this justifies my decision to stop solubility testing in unclean areas before further scientific investigation was conducted.

I am happy overall with the retouching. I initially used raw pigments with the same Laropal® A 81 resin as the binder and achieved satisfactory colour matching (above, second from left). The glossy appearance (above, third from left) of the inpainted areas upon drying was less agreeable and very distracting. This may be due to the fact that the initial brush-applied varnish seeped through the painting as opposed to settling on the surface. I decided to remove my inpainting and try again with watercolours (above, right). While these areas have a slightly more matte appearance, I think they are far less visually disrupting.

Like many conservation treatments, Untitled (Woman and Child) was more difficult than I had first thought. While weeks of solubility testing did become a little tedious, it was a great opportunity to research further into different types of aqueous phases, solvent gels and emulsions used for cleaning painted surfaces. While I’m still disappointed to leave the work only partially cleaned, I am confident that with further research into the effects of saponification in the sky and ocean sections, the painting may one day be returned to its former glory and proper colour saturation.

References

Listed below are some useful references for further reading into the main material and ethical concerns raised in this treatment:

- Bomford, D. 2012, ‘Picture Cleaning: Positivism and Metaphysics’ in J. Stoner and R. Rushfield (eds), Conservation of Easel Paintings, Routledge, London, pp. 481-491

- Digney-Peer S., Thomas K., Perry R., Townsend J. and Gritt, S. 2012, ‘The Imitative Retouching of Easel Paintings’ in J. Stoner and R. Rushfield (eds), Conservation of Easel Paintings, Routlegde, London, pp. 607-634

- Hedley, G. 1993, ‘On Humanism: Aesthetics and the Cleaning of Paintings’, in C. Villers (ed.), Measured Opinions: Collected Papers on the Conservation of Paintings, United Kingdom Institute for Conservation, London, pp. 172-178

- Keune, K. and Boon, J.J. 2007, ‘Analytical Imaging Studies of Cross-Sections of Paintings Affected by Lead Soap Aggregate Formation’, Studies in Conservation, vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 161-176.

- Phenix, A. and Wolbers, R. 2012, ‘Removal of Varnish: Organic Solvents as Cleaning Agents’ in J. Stoner and R. Rushfield (eds), Conservation of Easel Paintings, Routledge, London, pp. 524-554

- Wolbers, R. 2000, Cleaning Painted Surfaces: Aqueous Methods, Archetype Publications, London