One Step Forward, Two Steps Back: The Scenic Route of Decision-Making Process

“Every decision is a moment of madness”*

In his abridged version of ‘Die RiBverklebung’, the author-conservator Winfried Heiber (2003) quoted that very passage at the beginning of his introduction. The simple sentence embodies the ethical deliberation, technical reasoning, and institutional negotiation a conservator makes. A decision-making marathon one has to grow quite the muscle for. Such was the case for this painting, Untitled (Lady with Flowers) by Unknown and part of the Bendigo Art Gallery Collection.

There are countless conservation cautionary tales where a decision may lead to a disastrous outcome. More often than not, these decisions were not borne out of ill-intent, but perhaps from systematic limited access to appropriate resources and knowledge. This is where professional guidelines and ethical discourse of the profession came into play.

And what better example of an ethical pickle to be meditated on other than that of aesthetic treatment? The following sections will explore the layers of deliberations and mitigation strategies made in the treatment of one seemingly unassuming painting.

Step 1: Preliminary Investigation and an Attempt to Know What to Do

The painting in question is an untitled portrait of a lady, softly gazing to the viewer, holding a flower bouquet. Very little is known about this painting ever since it was donated to the Bendigo Art Gallery in 2010. Although the work was not signed or dated, the date of production can be narrowed down to the 19th-century based on its technique, aesthetic, material choice, and ageing characteristics. Another piece of breadcrumb was by examining the painting’s anatomy, wherein the case of this painting was its original tacking margin where square iron nails indicative of the era found to be (still) intact.

The painted subject is assumed to be the Irish-born dancer Lola Montez (1821-1861) which known for her infamous ‘spider’ dance and whose political counsel to King Ludwig I bring about the Bavarian revolution (Wright 2009). This portrait may be linked to the time Lola spent in the goldfields of Ballarat, Bendigo, or Castlemaine where her shows were considered to be a ‘ribald release from diggings life’ (Gilmour 2010). Nevertheless, further investigation needed to be done to verify the hypothesis.

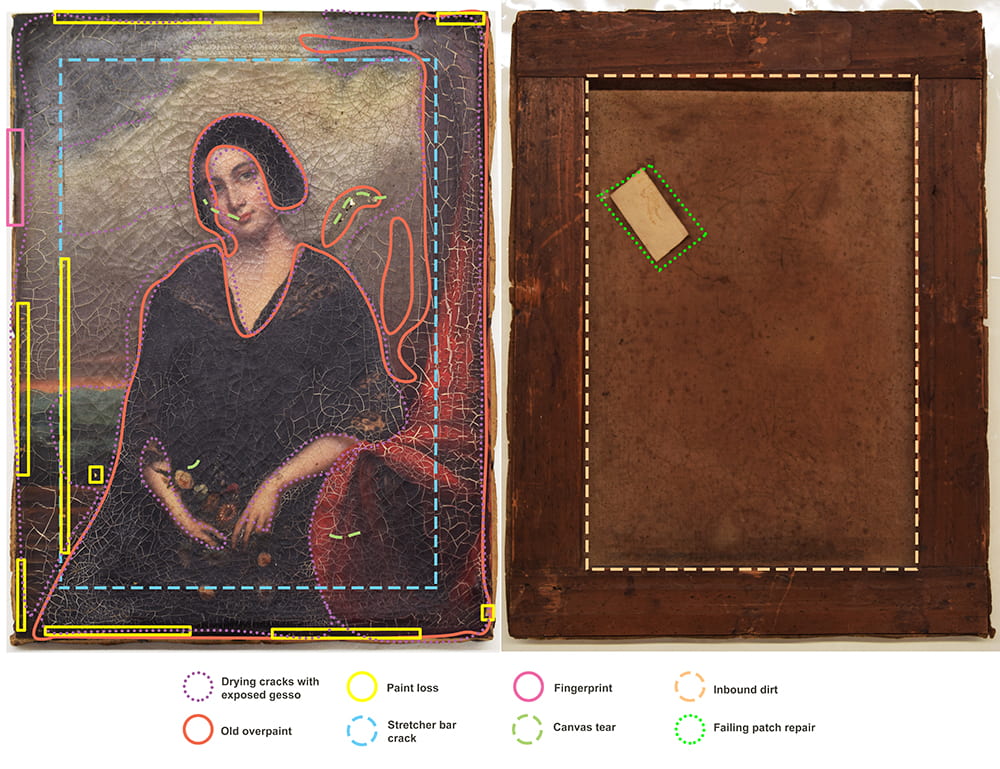

The painting was in poor condition with damages that greatly disrupts its structural and aesthetic integrity (Keene 1991). Other than suffering from a number of canvas tears, loss of tension, inbound dirt and discolouration, the picture plane was overtaken by an extensive network of drying cracks. Unlike cracks (or craquelure) caused by ageing or mechanical impact, drying crack, as the name suggests, occurs due to chemical processes and/or physical influences when it is drying; restricted only to the paint layer (Nicolaus 1999, p. 167). The artist’s technique and material choice largely influence the formation of this type of crack. A telltale sign of drying cracks is that they tend to reach as far as the ground layer, thereby visually disrupts the overall composition of the painting and exposing the painting’s inner layers to the immediate environment (Nicolaus 1999, p. 167).

After assessing the original material, its current condition, and primary issue, a treatment pathway then designed in the aim to reinstate both mechanical and visual cohesion of the work thereby restoring its cultural, historical, and educational values. Structural repairs were to be devised as the first phase to ready the painting for any aesthetic treatment; this includes dry cleaning, paint consolidation, wet cleaning, humidification and flattening, and tear repairs. An area of old retouching was identified and cleaned accordingly. The methods and materials used were deliberated carefully and chosen based on compatibility to the original surface, ageing properties, sustainability, and reversibility – the concepts which will be explored further down the line.

Step 2: Tailoring Bespoke Approach

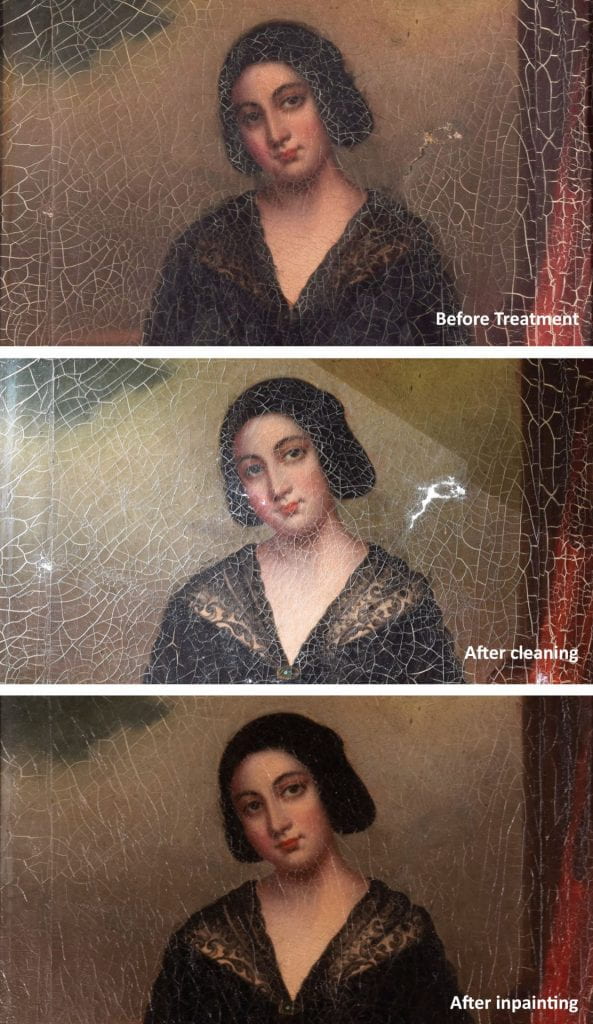

The painting is now ready to enter the second phase of the treatment – addressing aesthetic issues. The main approach in handling surface cracks is to do a visual compensation involving painting over areas of damages. The spectrum of visual compensation ranges from minimalist approach, where the aesthetic damages will often be left as is, to fully invasive methods such as overpainting the original material (Nadolny 2012, pp. 374-378). The right approach should be weighted on a case-per-case basis with sufficient reasoning. An objective strategy was devised not to eliminate the evidence of age but merely reducing its visual impact and with no attempt to misrepresent the artist’s intent (Digney-peer et al. 2013, p.608).

In the case of this painting, approaching the issue by reconstructive inpainting restricted in areas of loss was deemed appropriate as it is able to answer to the said objective. But we are only half-way through the deliberation. According to Jileen Nadolny (2012, pp. 575-576) reconstructive inpainting, in itself, can be differentiated into multiple types:

- Fully mimetic: to perfectly imitate the losses to the original where the repairs will only be discernible to highly trained professional, if at all.

- Mimetic with exceptions: to fully imitate with the exception of a slight detail (different gloss, varied topography, etc.) that enables it to be invincible from normal viewing distance, but marginally discernible in closer proximity.

- Differentiated mimetic retouching: same as above, but made to be clearly distinguishable at close range by how the inpainting is applied differently from the original (hatched lines, dots, etc.). Can be perceived as distracting if not executed mindfully.

- Suggestive differentiated retouching: to give a general indication of a complete image by using colours and shapes but without including any detail. If not done with care, the repair may, in turn, cause visual interference to the original.

It is important to acknowledge that all of these options, still, unavoidably introduces potential ethical issues revolving unwarranted visual alteration, the conservator’s subjective interpretation and incompatible material reaction (Digney-peer et al. 2012, p.608-634). However, each risk can be mitigated by having a well-defined treatment aim and expectations. In consideration of the established goal, the retouching will follow ‘mimetic with exceptions’ principle (Nadolny 2013, pp.575-576). By having the repair contained, controlled, and minutely discernible from the original, the risks should be able to be minimised.

Step 3: Material Choice

The next point to consider revolves around material behaviour. The choice of retouching materials should consider stability, ease of removal, and compatibility with the original surface (Digney-peer et al. 2012, p.613). The process of aesthetic repairs, such as inpainting involves the introduction of non-original materials. To lessen the risk of material disruption, an isolating varnish can be applied prior to the inpainting to provide physical protection between the original surface from the restoration material and saturates the surface to facilitate precise colour matching (Digney-peer et al. 2012 p.613).

After looking into the characteristics of potential resins, the conservation-grade commercial ketone resin MS2A is chosen because of its excellent ageing properties, ability to dissolve in low-polar solvents, and compatible refractive index with the painting (van der Goltz et al. 2012b, pp.646-647; Horie 2010, pp. 183-188). Teas solubility chart was used to determine the most appropriate solvent to be used as the resin’s carrier.

As for the inpainting, resin-based paint will be made by mixing loose pigments with 20% w/v MS2A so that all surface retouching, including the isolating varnish, can be easily removed in one sitting in future restoration.

Step 4: The Repair

With the logic and reasoning behind the steps straightened out, it is time to get down to business. First, the isolating varnish:

The varnish was applied with a brush to provide better penetration and evenness (van der Goltz et al. 2012, pp.636-637; Rivers & Umney 2003, p.598). The ‘Union Jack’ technique ensures better varnish distribution from the middle to the edges of the painting. The painting then placed inside a fume cupboard to help the varnish to off-gas and remained there overnight to dry.

And as the sun blesses the laboratory with its soul-warming natural light, the inpainting commences:

Detailed inpainting was done primarily in the focal point of the composition, that is the figure and the flower bouquet. The extent of inpainting was titrated to be less detailed further outwards from the subject. This approach created a more focused sense of completeness without eliminating evidence of age.

Step 5: Rinse and Repeat

After a total of approximately 10 hours of interweaving madness (read: examination, literature research, discussion, material testing, soul searching and morning meditations) the inpainting was finished and the treatment moved on to its final stages of rehousing and documentation.

As said before, the process of figuring out the most appropriate approach will depend on each given case. The entirety of this restoration was comprised of 22 steps where each of them involves the same, if not more, amount of careful deliberations. By the end of the day, ensuring the continuation of values contained within an object while operating within professional guideline must become the primary objective of any treatment.

So, I would answer to both Kierkegaard and Chesire cat – “No, we’re not mad. We’re just consciously taking the scenic route”.

_

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude for Dr Nicole Tse for her supervision and guidance; Dr Jonathan Kemp for his professional opinions in times of confusion; the Senior Registrar of Bendigo Art Gallery, Sarah Brown, for her insights on the painting; and fellow students at the Grimwade Centre for Cultural Materials Conservation for being my constant companion – in and off the laboratory.

* Soren Kierkegaard (Derrida)

References

Australian Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Material (AICCM) 2002, Code of Ethics and Code of Practice, Australian Institute for Conservation of Cultural Materials, Australia.

Digney-peer, S, Thomas, K, Perry, R, Townsend, J & Gritt, S 2012, ‘The imitative retouching of easel paintings’, in JH Stoner & R Rushfield (eds), Conservation of Easel Paintings, Taylor and Francis, London and New York, pp.607-634.

Fuster-Lopez, L 2012, ‘Filling’, in JH Stoner & R Rushfield (eds.), Conservation of Easel Paintings, Taylor and Francis, London and New York, pp.585-606.

Gilmour, J 2010, ‘You beauty’, Portrait magazine, viewed on 26 March 2020, <http://www.portrait.gov.au/magazines/37/you-beauty/>.

Heiber, W 2003, The Thread-by-Thread Tear Mending Method, Courtauld Institute, London.

Horie, CV 2010, Materials for Conservation: Organic consolidats, adhesives, and coatings, Butterworth Heinemann, Oxford.

Keene, S 1991, ‘Audits of Care: A framework for collections condition surveys’ in Storage: Preprint for UKIC conference Restoration ‘91, UKIC, London, pp. 6-16.

Nadolny, J 2012, ‘History of visual compensation for paintings’, in JH Stoner & R Rushfield (eds.), Conservation of Easel Paintings, Taylor and Francis, London and New York, pp. 573-585.

Nicolaus, K 1999, The Restoration of Paintings, Kӧnemann, Cologne.

Rivers, S & Umney, N 2003, Conservation of Furniture, Routledge, United States.

Wright, C ‘A Lover and a Fighter: the Trouble with Lola Montez’, Overland, accessed March 26, 2020, from <https://www.academia.edu/39687558/A_Lover_and_a_Fighter_the_Trouble_with_Lola_Montez>.

von der Goltz, M, Proctor RG, Whitten, J, Mayer, L, Myers, G, Hoenigswald, A & Swicklik, M 2012, ‘Varnishing as part of the conservation treatment of easel paintings’, in JH Stoner & R Rushfield (eds.), Conservation of Easel Paintings, Taylor and Francis, London and New York, pp. 635-657.