Middle Eastern Manuscripts

The Grimwade Centre for Cultural Materials Conservation is happy to announced that four manuscripts from the University’s Middle Eastern Manuscript Collection are now on display in Arts West.

Introduction to the Middle Eastern Manuscript Collection

In 1959 Middle Eastern scholar Professor John Bowman (1916-2006) arrived at the University of Melbourne and began to expand the Department of Semitic Studies. He established two journals

Abr-Nahrain (now Ancient near Eastern Studies) and Milla waMilla: the Australian Bulletin of Comparative Religion and built a department of scholars from Australia, England, Finland, Iran, Pakistan and Syria. One of his most significant legacies however was the collection of Middle Eastern manuscripts, now held in the Rare Books in the University Library.

Professor Bowman’s work embedded in text and the collection comprised in Arabic and Persian, as well as Turkish, Urdu, Ethiopic, Syriac, Hebrew, Sanskirt, Pushtu, Prakit and Mongol scripts.

The texts include Islamic religious texts, including Qur’ans and commentary on the Qur’an, as well as significant poetic works, educational textbooks and writing on history, biography, astrology, mathematics, philosophy and weaponry.

The texts include Islamic religious texts, including Qur’ans and commentary on the Qur’an, as well as significant poetic works, educational textbooks and writing on history, biography, astrology, mathematics, philosophy and weaponry.

In 1975 Professor Bowman retired and the Department was subsumed in a university restructure. The extraordinary collection he amassed was moved across to the University Library, where it existed, safe but invisible for twenty years.

In 1995 Australian Research Centre funding, awarded to the University’s Conservation Centre, in partnership with the School of Physics, to undertake scientific analysis of specific manuscripts in the collection. This enabled Raman analysis of the most beautifully illustrated text. Specific pigments were analysed and translations of treatises on pigment and ink production were examined to determine the materials used to illustrate the pages.

The manuscripts are internationally significant. In 2007 scholars from around the world took part in the Symposium on the Care and Conservation of Middle Eastern Manuscripts at the University of Melbourne. Expert visiting scholars have come to investigate the materials and techniques and the writings of which the manuscripts are compromised. Currently four PhD students at the Grimwade Centre for Cultural Materials Conservation are working on John Bowman’s collection. Their work is showcased here.

Manuscripts in the #ArtsWest Display

MUL 86

Title: Ḥadīqah al-Ḥaqīqah

Author: Abu al-Majd Majdūd ibn Ādam Sanāʾī Ghaznawī (11th -12th century)

Date of transcription: 1540s (950s AH)

Place of transcription: Tabriz, Iran

Language: Persian

Scribe Ali Husayni Imad/Al-Hasani Imad (This name was added by a different hand on a rubbed area on the colophon.)

Calligraphic style: Nastaʿlīq

University of Melbourne collection MUL 86

This manuscript is a copy of some selected verses of a famous mystical poem called Ḥadīqah al-Ḥaqīqah (The Enclosed Garden of Truth) by Sanāʾī Ghaznawī. Sanāʾī was a famous mystic poet of the 16th century. He got influenced so deeply by a Sufi nicknamed Lāykhār (drinker of dregs) that left his career as a court poet and lived as a Sufi renouncing all attachments to this world. The rhymed couplet of Ḥadīqah is considered the first example of mystical poetry in Persian literature which had a great impact on proceeding poets such as Rumi. It consists of more than 10000 verses composed on subjects like God, Love, prophecy and reason (Bruijn 1983).

Referring to the colophon at the end of this manuscript, this copy was transcribed in 950s AH/ 1540s (at the time of the first Ṣafavīd king, Shah Ismāīl) in the capital city of Ṣafavīd daynasty (Dār al-Salṭanah), Tabriz. Some of the words of the colophon were corrupted and the name of the calligrapher was added by a different hand on a rubbed area trying to attribute the calligraphy to Al-ḥasanī ʿImād. This copy has been written in a superb Nasta’līq calligraphy of the 16th century showing respect for proportion, composition and refinements of written letters and words.

Nastaʿlīq is one of the 10 famous styles of calligraphy, Kufic, Naskh, Muḥaqaq, Thuluth, Tawqī’, Riqā’, Ghubār, Ta’līq, Nastaʿlīq and later on Shikastah which were developed in Islamic civilization. Nastaʿlīq was born in the 14th century in Iran. It is said to have been invented by Mīr ʿAlī Tabrīzī (d. 1446-47 AD). In Iran, after the 15th century, most writings were prepared in this style. Nastaʿlīq reached its zenith in the Ṣafavīd period and that was when the great calligraphers like Sultān ʿAlī Mashhadī (d. 1520 AD) and Mīr ʿImād Ḥasanī (killed 1615 AD) came to power (Yūsofī 1990). Many of famous calligraphers produced calligraphy treatises in which they described characteristics of a superb calligraphy work and the way of mastering it. According to the famous calligraphy treatise, Ādāb al-Mashq (the habitudes of calligraphy) by Bābā Shāh Iṣfahānī (d. 1588AD) mastering calligraphy needs three necessary considerations: refinement of the soul, continuous practise, and choosing a master (Māyil Haravī 1993).

Choosing a master was regarded as an important factor to the degree that learning calligraphy without having a master was considered a useless try. The master taught his pupil not only the delicacies of producing a superb calligraphy but also the mystic way of living. This mentee-mentor relationship usually continued until their death (Qayoumi, 2008). This process gave birth to many Sufi master calligraphers such as Shāh Maḥmūd Nayshābūrī who were not attracted to material life.

The trend toward self-refinement was the common trend between Sufi poets and calligraphers. Islamic manuscripts are products of this unity where you can find their text and calligraphy go hand in hand producing a masterpiece. This is the case with the existing copy of Ḥadīghah (MUL 86) where we can see mystical verses written in a superb Nastaʿlīq calligraphy producing a valuable work of art and literature.

References

Bruijn, Jd 1983, Of piety and poetry : the interaction of religion and literature in the life and works of Ḥakīm Sanā’ī of Ghazna, Brill.

Māyil Haravī, N 1993, Kitābʹārāyī dar tamaddun-i Islāmī : majmūʻah-i rasāʾil dar zamīnah-ʾi khvūshnivīsī, murakkabʹsāzī, kāghaẕgarī, taẕhīb va tajlīd : bih inz̤imām-i farhang-i vāzhigān-i niẓām-i kitābʹārāyī / taḥqīq va taʾlīf-i Najīb Māyil Haravī, Mashhad : Muʾassasah-ʹi Chāp va Intishārāt-i Āstān-i Quds-i Raz̤avī, 1372 [1993].

Qayoumi, M 2008, ‘Ādāb Nāmah hāyi Mashq dar Maqām-i Manābiʿ-i Hunar-i Iran’, Gulistān-I Hunar, vol. 3, no. 4, p. 40.

Yūsofī, GH 1990, ‘Calligraphy’, Encyclopaedia Iranica, vol. IV, no. 7, pp. 680-704, viewed 2 June 2016, < http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/calligraphy>

Written by Leila Alhagh, PhD candidate.

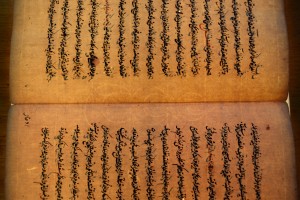

MUL 33

Title: Multaqā al-ʾAbḥur (The meeting point of the oceans of knowledge)

Author: ʾIbrāhīm ibn Muḥammad ibn ʾIbrahīm Ḥalabī Ḥanafī (d. 955AH-1548AD)

Date of transcription: 23 Ramadan 1048 (Friday 28 January 1639)

Date of the creation of the book: Tuesday, 13th of Rajab 923 AH (1 August 1517)

Scribe: Unknown

University of Melbourne collection MUL 33

‘Ibrāhīm ibn Muḥammad ibn ‘Ibrahīm Ḥalabī Ḥanafī was one of the greatest Sunni scholars who studied Islamic Jurisprudence (Fiqh) and Hadith in the city of Al-Sham (the region bordering the eastern Mediterranean Sea, which is now Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Israel, Jordan, Cyprus and the Turkish Hatay Province) and Egypt and later became a famous khatīb (A person who delivers the sermons during Friday and ‘Eid prayers) of the Sulṭān Muḥammad Fātiḥ mosque in Istanbul, Turkey.

Multaqā al-Abḥur is one of his famous works which is on the Fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence) of the Hanafi school and has been published in turkey and Egypt so many times. He was died in year 956 AH (1549AD) when he was 90 years old (Tabrizi 1990).

The date of death of the author of this manuscript was written by the scribe in last sentences of the book (page 27R-right hand side, right margin). The recording date of death is 955AH-1548AD.

Information about this manuscript can also be gained through investigation of the papers and other materials components. Within MUL 33 a three crescent watermark known as tre lune (pictured below) is commonly found. The watermark process embeds a faint design into the handmade sheet at the time of manufacture. The term watermark if misleading as the mark or design is embedded into the sheet for manipulating wire on the paper marking screen not through a water process. The paper pulp than settles on the screen around the wire deign causing areas of less pulp. Once dry, the watermark can be seen by holding the sheet up to the light because the areas of less pulp allow light to be transmitted (Turner 1998, p. 32). According to Bloom (2001, p.6) the Italian paper makers were the first to introduced this technique in the late thirteenth century.

There are several variations on the crescent watermark design and it is believed to have originated in Italy in the early sixteenth century.

References

Bloom, J 2001, Paper before Print: The History and Impact of Paper in the Islamic World, Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

Tabrizi, MH 1990, Reyhanat al-Adab, Tehran: Khayam Publication, 1369 [1990].

Turner, S 1998, The Book of Fine Paper, Thames and Hudson, London.

Written by Sophie Lewincamp and Leila Alhagh, PhD candidates.

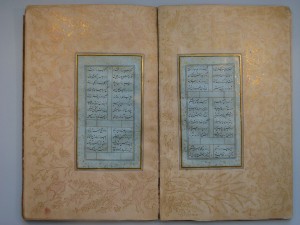

MUL80

Title: Complete Collection of Poetry

Author: Muhammad ībn Yūsūf Ahlī Shīrāzī (Mawlānā Āhlī Shīrāzī) 1454-1545 Shiraz, Iran

Date of transcription: Probably 16th century

Scribe: Unknown

Place of transcription: Iran (Persia)

Language: Farsi (Persian)

Calligraphic style: Nastaliq

University of Melbourne MUL 80

This manuscript is the complete poems of Muhammad ībn Yūsūf Ahlī Shīrāzī also known as Mawlānā Āhlī Shīrāzī, a Sufi (Mystic) poet who lived during the 15th-16th C in Shiraz, Iran which corresponds to the Safawid dynasty of Persia (Emdad 1998). His style of poetry includes ḡazals, qaṣīdas and robāʿīs (Thackston 2014). The poems are written in beautiful Nastaliq script, the most celebrated calligraphic style of Persia (current day Iran and Afghanistan).

Calligraphy is considered a form of Islamic art which is a term often heard in the Middle-East. According to Zekrgoo (2007, pp.5-13), Islamic art is divided in to sacred art, and non-sacred art. The first refers to any form of art that developed through expressions of devotion and respect for the one divine being, i.e. god, while the latter might have manifested from a sacred source but it is not necessarily considered sacred.

For example, a verse of the holy Qur’an which is written in certain calligraphic styles is sacred since it is religious/holy text, whereas a couplet of poetry in the same style is not. However, since the Arabic script was created in accordance to the divine order for the literacy of mankind, any form of art that involves this script, such as Persian calligraphy, is considered Islamic (Zekrgoo 2012);

Poetry was and still is a big part of Persian and Middle-Eastern culture; it is practiced daily and it is integrated within the language. Of course one thing that goes hand in hand with poetry is calligraphy. Due to its importance, great value has been given to the type of ink used for calligraphy and master calligraphers experimented with various materials to create the best inks. Information regarding these inks are passed down through their treatises in the form of recipes, a considerable amount of which are in the form of poetry; partly due to its cultural importance but also due to the rhymes acting as mnemonics to help memorise recipes.

As the calligraphic styles evolved over decades and centuries, so did the inks. Zekrgoo (2014) has been investigating recipes on Persian inks and re-creating such inks. Based on his research, he has divided Persian inks in to the following:

- Carbon ink: A mixture of lamp black (soot) as the colourant and gum Arabic as the binder

- Iron-gall ink: A chemical reaction between vitriol (metal sulphates) and extract of gall nuts (containing gallic acid) resulting in the colorant and addition of gum Arabic as the binder

- Persian ink: A mixture of the ingredients of the 2 inks mentioned in set proportions; 1 part lamp black, 1 part vitriol, 2 parts gall nuts, 4 parts gum Arabic

- Peacock ink: The most celebrated ink amongst calligraphers, this ink uses the 4 main ingredients with said proportions seen in Persian ink, with the addition of many secondary ingredients such as indigo, woad, saffron, henna, myrtle, aloe, etc. giving the ink different shades of colour and different characteristics

- Starch ink: At times, burnt starch was used as the main ingredient. In addition to it being used as the main colourant, due to its sticky nature, the burnt starch mixed with hot water was also used as a binder

Written by Sadra Zekrgoo, PhD candidate.

References

Emdad, H 1998, Simay-e sha’eran-e farsi dar hezar sal, Ma Publishing House, Tehran.

Thackston, W 2014, Ahli Sirazi, Encyclopædia Iranica, I/6, pp. 637-638

Zekrgoo, A. H. 2007, ‘Islamic manuscripts: differentiating the sacred, religious & non-religious’, International Symposium on the Care and Conservation of Middle Eastern Manuscripts, Melbourne, pp. 26-30.

Zekrgoo, S 2012, Methods of Creating Traditional Persian Ink: A Historical and Analytical Overview, Master’s Thesis. Northumbria University, Newcastle Upon Tyne, United Kingdom.

Zekrgoo, S 2014, ‘Methods of Creating, Testing and Identifying Traditional Black Persian Inks‘, Restaurator, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 133–158.

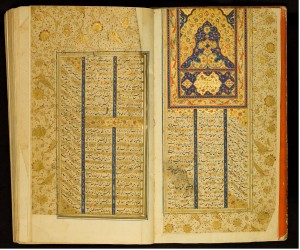

MUL59

Author: Abu Muhammad Muslih al Din bin Abdallah Shirazi (Sa’di)

Title: Gulistan (The Rose Garden) گلستان

Scribe: Ahmed Ali

Date of transcription: 1836

Place of transcription: India

Language: Farsi (Persian)

Calligraphic style: Nasta’liq

The manuscript is a complete book of Gulistan written by Sa’di, the famous 13th century Persian poet. Ahmad Ali transcribed the text in 1036 H.A (1836) for Charles Marriot Caldecott. This is made apparent by the scribe’s signature on the concluding page written in Farsi. Although little is known about Caldecott, he commissioned Gulistan during a period in which Orientalist studies proved to be very influential. Persian poetry and literature also had a profound influence on important German literature, including the works of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Sa’di was prolific writer and poet and his writings have been a major influence on subsequent literary works in the Persian speaking world and beyond. This beautifully written and ornate copy of the Gulistan in Nast’aliq style calligraphy is one such example of the popular movement of literature from East to West.

Gulistan is a collection of morality tales and personal reflections presented in a mixture of prose and verse. The stories deal with the dilemmas faced by humankind. Despite the dedication of his works to powerful rulers, his intended audience is known to be those in the sidelines of power; he had a strong empathy for the vulnerable and weak who were hoping to survive the harsh conditions of that time.

The following is an English translation of a renowned poem from Gulistan:

Human beings are members of a whole,

In creation of one essence and soul.

If one member is afflicted with pain,

Other members uneasy will remain.

If you have no sympathy for human pain,

The name of human you cannot retain.

(Gulistan, Chapter One translated by M. Aryanpour)

Written by Nur Shkembi and Sophie Lewincamp.

Sizing material

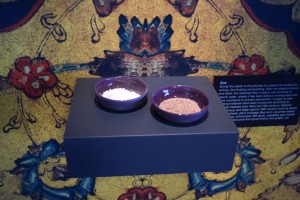

Image: starch powder and fleawort

Sizing the paper is the process to prepare the surface suitable for writing, illuminating and painting. After the sheet is formed and dried, the cellulose fiber in paper can continue to absorb water, unless it has been sized or impregnated with some substance to prevent penetration. A large number of sizing materials have been introduced according to historical treatises from Taimurid (15th century), Safawid (16th century) and Qajar period (19th century) such as starch (rice and wheat), plant mucilage (fleawort, cucumber seeds, marshmallow), animal glue (fish glue), vegetable glue (serish, gum-arabic), fruit juice and syrup (melon and grape), etc.

Written by Dr Mandana Barkeshli

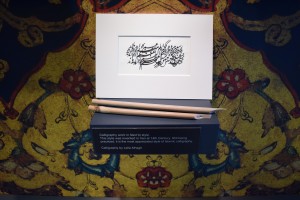

Calligraphic sample

Image: Calligraphy work in Nast’ῑq style, Sῑyᾱh Mashq by Leila Alhagh

This style was invented in Iran at 14thCentury. Still being practiced, it is the most appreciated style of Islamic calligraphy.

Sῑyᾱh Mashqis a genre of Nasta‘lῑq calligraphy which is based on rhythm and repetition. It was originally used as a practice method for calligraphers to warm up their hands before they started to write the actual calligraphy work. In the second half of 19th century, it became an independent genre of calligraphy executed for the sake of composition and style.

Translation: Arrived the glad tidings that grief’s time shall not remain:

Like that (joyous time) remained not; like this shall not remain.

Ghazal 179, Hafiz