Is your voice really your voice? Let’s ask AI Debbie

Advances in artificial intelligence (AI) have been extremely rapid, and this has become especially evident in 2023. In this blog post, we address the the matter of text-to-speech. Think deepfakes (in this case generated audio) and spoofing (here, identity crime using voices) – but also there are more innocuous uses for the generation of speech, such as for a variety of accessibility reasons.

Here are some examples of what kinds of things can be done with text-to-speech. This example document is written for Descript, which is a commercial company, and we will be focusing on the AI functions in Descript in this post (this post focuses on functions in the free version).

AI in the Hub

Artificial intelligence is of particular interest for us in the Research Hub for Language in Forensic Evidence. We have been focusing on some of the most recent developments in AI because of the implications for forensics, and for some of the broader theoretical and ethical issues that can arise in this space as well. For example, we have looked at:

The role of automatic speech recognition (speech-to-text) in forensic transcription, for example see:

- this guest blog by Will Somers and this follow up about ‘Humans vs Machines’

- a blog post about our research presentation at Monash University

- a paper by Loakes 2022 – this is currently in the process of being updated, focusing on the newer generation of systems

Enhancing forensic audio for example:

- a presentation by Helen Fraser

- this Conversation piece

- an earlier paper by Helen on the issue titled Enhancing’ forensic audio: what if all that really gets enhanced is the credibility of a misleading transcript

In this blog post, we look at one technique for generating voices, consider how it works, and we also have a think about the implications. This blog post merely touches on the surface of what is available.

Testing out Descript’s voice generation feature

Helen mentioned to me that Descript has a whole host of AI features, which would be interesting to look at for the Hub. As mentioned, we had been trying out the transcription (speech-to-text) functions, but a recent update has included text-to-speech functions as well.

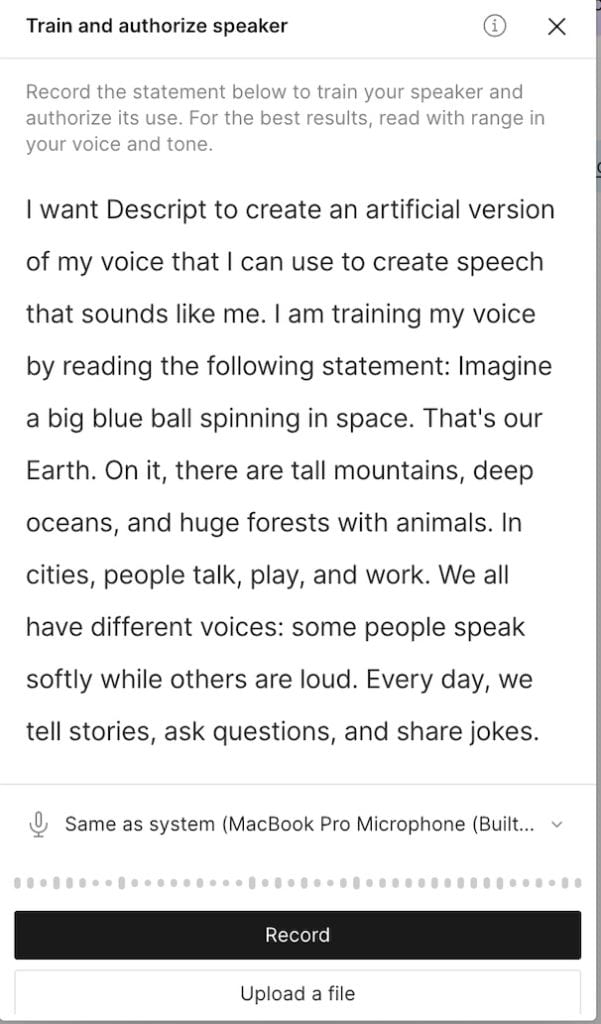

Descript asks for a test sample of speech. I did this, effectively making an “AI Debbie” voice. I needed to say a very specific set of phrases, as shown below:

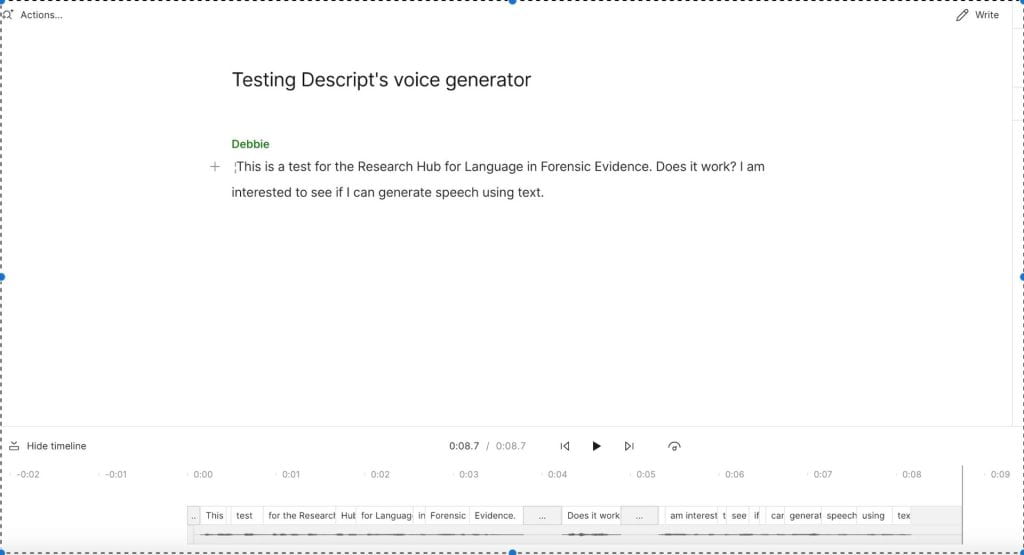

Making an AI Debbie was very quick. If you want to try this too, you can try following the steps I used. Essentially, once this “new speaker” was available from a dropdown list (which also includes stock AI speakers), I selected “+new ” then I selected “audio project”. I gave the project a name, then I typed the text you can see below. I made sure to choose “Debbie” as the speaker.

Not long after typing, this utterance was created using the AI version of my voice. I had to wait for only about a minute for the audio to generate. You can listen to this generated speech in the file below. Please note that the free version of Descript only comes with 1001 words in the vocabulary, so it replaces some words with “jibber” and “jabber”.

I think this is a very good attempt. Of all the files in this blog post, I think this is the best one. I wonder if other people think this sounds like me? This is how real Debbie would say the same thing:

I also did a second test, with some different vocabulary and phrasing, just to see what would happen. This is what I typed:

It is past midnight and I am very tired, but it so interesting generating speech. I wonder if Descript knows words like “sociophonetics”, “laryngoscope” and “pinot noir”? Or will the system replace these words with “jibber” and “jabber”?

You can hear the AI Debbie version of this in the sound file below.

I think this one is definitely not as good as the first attempt, perhaps due to the length (a longer utterance than the previous one) or because of the words I chose. One funny thing I was not expecting is that the word midnight was replaced with applesauce! AI Debbie version has some obvious differences from how I would normally say certain words – for example you can hear that I say laryngoscope differently, and I would use a different intonation pattern for a question (i.e. on “pinot noir”). You can hear the real me saying the sentence with these words below:

After doing this activity, I decided to record myself saying something, then I used the auto-transcribe function in Descript, then I fed that transcript back to AI Debbie (I was asking Descript to regenerate my speech).

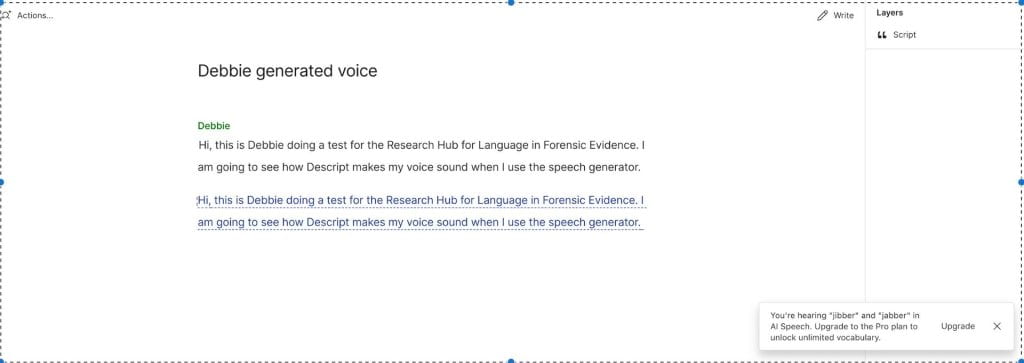

Here is a screenshot of what it looked like when I worked on it, so you can see what the words are. You can also see the warning about jibber and jabber on the bottom right-hand side of the image.

And now you can have a listen to the two files back-to-back, in the file below! The real me is first, and then you will hear AI Debbie.

Something to listen out for is the obvious differences in prosody. For example you will hear that real Debbie has a wider pitch range overall. Interestingly, the AI model has copied the creakiness I was using at the end of my utterances (you can hear this in other utterances in this post as well). Another thing is that I spoke more slowly than I normally would, because once I pressed record I had to think about how to phrase what I wanted to say. Real Debbie’s utterance is about 12.1 seconds, while AI Debbie was quicker at about 9.7 seconds. One thing that is surprising is that the AI version also models the intake of air (the “in breath”) in between the phrase forensic evidence and I am going to – I think it must be learning from any new speech I include!

Focusing on some of the detail in AI Debbie’s voice

There are some things about the AI voice which do not seem completely authentic for my voice. One example is the Australian English /i:/ vowel (my real one has more of an “onglide”), but still I feel it sounds similar to recordings I have heard of myself.

To compare how AI and real Debbie say speech, you can listen to the two versions of the phrase but it is so interesting generating speech – the vowels are definitely not the same! In this file, AI Debbie speaks first.

You could probably also hear some differences in pitch (or “melody”) as well as stress (“emphasis”).

Thinking more about pitch and focusing now on the phrase Hi, this is Debbie doing a test for the Research Hub for Language in Forensic Evicence, we can hear that real Debbie had a low pitch on the greeting hi, while AI Debbie used a high pitch. Real Debbie also used a high-rising tune on evidence, while AI Debbie had a falling pitch. You can hear this in the following file (real Debbie is first):

Across these two utterances, the pitch is doing completely opposite things going from low to high for real Debbie, and high to low for AI Debbie! I presume the system is modelled to start utterances with a high pitch which falls towards the end when it is a statement. It is completely typical for Australian English to have high-rising tunes for both statements and questions (read this abstract for further information).

Thinking about some forensic implications

The forensic implications for being able to generate voices are obvious. If you would like to think about this a little more, you can read this article in the Guardian where attention has been drawn to issues of security surrounding AI generated voices. This article focuses on Australian organisations that use voice technology as part of the process of verifying people’s identity.

Finally, if you found this post about generating speech interesting, don’t forget to have a look at other Hub work on AI, such as our blog posts about automatic speech recognition by Will Somers, and a presentation by Lauren Harrington, Debbie Loakes and Helen Fraser, as well as the issues surrounding enhancing forensic audio in a presentation by Helen Fraser.

References

Fletcher, J. and J. Harrington (2001) High-Rising Terminals and Fall-Rise Tunes in Australian English Phonetica 58 (4) 215-229.