Research Report – Forensic audio in context: a study in perceptual phonetics

This is a post by Conor Clements who did his Honours thesis with me (Debbie Loakes) last year.

Over the course of 2020, I ran an experiment for my honours thesis on the topics of forensic transcription and the effects of priming and enhancing on perception of indistinct audio. My experiment followed on from an earlier one by Helen Fraser, so before reading about my research, you might like to have a look at this short article which explains Helen’s experiment – and also lets you listen to the audio for yourself before reading other people’s interpretation. One of the goals of this blog post is to explain the purpose of my study to the 182 people who participated in it. I am deeply appreciative of those who took part and hope some of them read this and are interested in the findings! I also want to share the results more widely, as they have some important implications.

Background

If you looked at Helen’s experiment, you may have just read that it was based on audio used in a true crime documentary. The audio was initially unintelligible, but the documentary claimed that ‘enhancing’ had revealed four incriminating phrases (we can call them the movie phrases). Helen’s experiment showed that when participants listened to the audio ‘cold’ (without any information) no one heard anything remotely like the movie phrases in either the original or the ‘enhanced’ version (the latter sounded less harsh on the ears, but was no more intelligible). In fact, hardly any participants heard any words at all, and no two heard the same words. This showed the movie’s ‘enhancing’ had not made the audio objectively more intelligible. Interestingly, however, when the movie phrases were suggested to the participants, some of them claimed to hear those exact phrases. This is an example of priming. If you are not familiar with the concept of priming, this short article by Kate Burridge is an excellent introduction to the topic. Helen’s more important finding, however, was that participants listening to the ‘enhanced’ version were more likely to be persuaded by the movie phrases than those listening to the original audio. That might be taken to mean that the enhancing was successful – except that we know from other sources that the movie phrases are not a reliable interpretation of the audio (in fact there is good evidence it is not speech at all). Helen concluded that while the movie’s ‘enhancing’ had not improved the objective intelligibility of the audio – it had improved the credibility of an unreliable transcript. That is pretty important when you consider that this audio is being used as evidence to show who (allegedly) committed a murder. So with that background, we can go on to look at my own experiment, which aimed to explore these effects a little further.

My experiment

My experiment used only the ‘enhanced’ audio from the movie. The aim was to explore what happened to participants’ perception of this audio when they were given various kinds of information about the audio. So in reading my results, it is very important to keep in mind that all the participants listened to the same audio throughout the whole experiment – and that audio was the ‘enhanced’ version from the movie (that the movie claimed made the movie phrases easy to hear).

Phonetic analysis

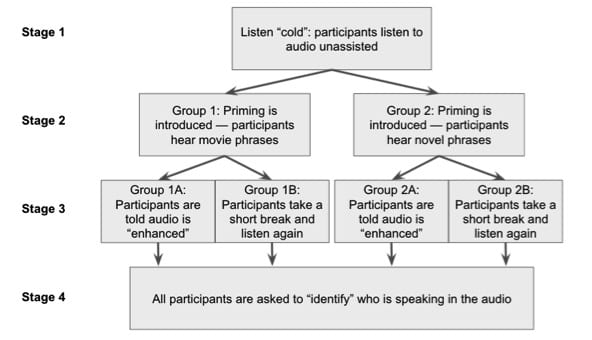

The first thing I did was a detailed phonetic analysis of the enhanced audio. This revealed that there aren’t really any identifiable segments (individual ‘sounds’) in it—that is, it doesn’t really resemble speech much at all. Then I built the audio into an experiment with four stages. Stages of the experiment This flowchart shows the path taken by participants through the experiment.

In Stage 1, all the participants listened ‘cold’ – with no information about what they were hearing. You now know they were listening to the ‘enhanced’ audio, but they were not told this during the experiment. In Stage 2, participants were divided into two groups. Group 1 were asked to consider the suggestion that the audio contained the movie phrases. Group 2 were asked to consider the suggestion that the audio contained four novel phrases that I made up for the experiment.

In Stage 3, Groups 1 and 2 were further divided. Groups 1A and 2A were told they were now being presented with an enhanced version of the audio. This was a little bit of deception – in fact they were listening to the same audio they had been listening to all along (the ‘enhanced’ version from the movie, and from Helen’s experiment). Groups 1B and 2B were not given any new information, but were simply asked to listen again to see if this helped them hear the audio better.Finally in Stage 4, all groups were asked to identify the ‘speakers’ of each of the four phrases as male, female or child (a deliberately leading request, as of course there weren’t any speakers). With that broad overview of the experiment, let’s look at my results.

Results

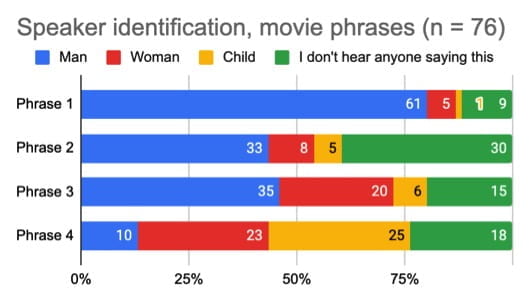

At Stage 1 (listen cold), only 6.6% of participants (10 people) were able to form any opinion about any words they might have heard. And for those who wrote down words they thought they heard, none of them wrote the same thing. This confirms Helen’s finding that the ‘enhanced’ movie audio was actually unintelligible. At Stage 2 (phrases suggested), the movie phrases had a strong priming effect. This was especially true for the movie phrases, where, for example, three of the phrases were ‘heard’ by a majority of the participants—67% reported hearing “We’re not speaking to you”, 70% reported hearing “Help me Jesus”, and 58% reported hearing “What did you find?”. Recall that these phrases are not accurate – and participants did not hear them until they were suggested. The novel phrases also had a priming effect, but this was not as strong as that of the movie phrases. This may be because in devising the novel phrases I paid too much attention to using segments (individual sounds) similar to those in the movie phrases, and not enough to the prosody of the movie phrases (their overall rhythm and melody). This is a good lesson – making up plausible but wrong interpretations of indistinct audio can be quite hard! Stage 3 also had interesting but complex results. Remember that half the participants were told they were being given an enhanced version of the audio (when really they were just listening to the same audio again). This false information caused an increase in acceptance of the suggested (inaccurate) phrases. The other half of the participants were simply asked to listen again (without being told they were listening to new audio, or being given any new information). This caused an even bigger increase in acceptance of the suggested (inaccurate) phrases. This is important as it shows that repeated listening can serve to entrench an inaccurate perception. Rather than improving their hearing it can actually give listeners more confidence in inaccurate hearing. It also indicates that some of the claimed effect of enhancing indistinct audio might come simply from repeated listening. Finally in Stage 4 (where participants were asked to categorise the ‘speakers’ of the phrases as male, female or child), participants who were given the movie phrases were more likely to identify ‘voices’ as belonging to a male, female or child, compared with those who were primed with the novel phrases (see the two figures below). When we recall that there actually were no speakers, this shows how easily people can be misled in their perceptions of forensic audio once they have been persuaded that it contains meaningful words.

One particularly interesting finding was that participants who possessed some form of training in linguistics were no less susceptible to the effects of priming than those who lacked training, and were in fact on average more confident in accepting the inaccurate transcription when it was suggested. This parallels a finding about people who have training in an interrogation method in the U.S called the Reid Technique (Harris, 2012). It has been shown that those who have received this training are no more accurate in their judgements of whether suspects were lying but can be “more self-confident and more articulate about the reasons for their often erroneous judgments” (Kassin & Fong, 1999: 512). This indicates that forensic transcription is a specialist branch of linguistic science, and gaining proficiency requires training beyond just education in linguistics or phonetics. What can we take away from these findings? It is clear that both of the (inaccurate) transcripts used in this study had a priming effect on the participants’ perception of the audio, although the movie phrases were particularly powerful. The findings also confirm that while priming may vary in its effectiveness (i.e. listeners cannot be primed with just anything), it almost always results in listeners reporting that they suddenly hear words where they previously could not. This study adds to the growing body of literature which shows: a) the need for people to understand the effects of priming, especially how priming interacts with ‘enhancing’; and b) the necessity for reforms to be conducted so that the risk of injustice arising from primed perceptions of forensic audio can be removed entirely (one of the goals of the Hub).

References

Burridge, K. (2017). The dark side of mondegreens: how a simple mishearing can lead to wrongful conviction. The Conversation.

Fraser, H. (2018). Forensic transcription: how confident false beliefs about language and speech threaten the right to a fair trial in Australia. Australian Journal of Linguistics, 38(4), 586-606. https://doi.org/10.1080/07268602.2018.1510760

Fraser, H. (2019). Don’t believe your ears: ‘enhancing’ forensic audio can mislead juries in criminal trials. The Conversation.

Fraser, H. (2020). ‘Enhancing’ forensic audio: what if all that really gets enhanced is the credibility of a misleading transcript? Australian Journal of Forensic Sciences, 52(4), 465-476. https://doi.org/10.1080/00450618.2018.1561948

Fraser, H., Stevenson, B. & Marks, T. (2011). Interpretation of a crisis call: persistence of a primed perception of a disputed utterance. International Journal of Speech, Language and the Law, 18(2), 261-292. https://doi.org/10.1558/ijsll.v18i2.261

Harris, D. A. (2012). Science and traditional police investigative methods: a lot we thought we knew was wrong. In D. A. Harris (eds.), Failed Evidence: Why Law Enforcement Resists Science NYU Press. 18-58.

Kassin, S.M and C.T Fong (1999) “I’m innocent”!: Effects of training on judgements of truth and deception in the interrogation room. Law and Human Behaviour 23 (5): 499-516.

Innes, B. (2011). R v David Bain: a unique case in New Zealand and linguistic history. International Journal of Speech, Language and the Law, 18(1), 145-155. https://doi.org/10.1558/ijsll.v18i1.145