Event Summary – SocioPhonAus3

This week, the Hub travelled to Brisbane for the SocioPhonAus3 conference, held on July 11 and 12. This was hosted by Griffith University, at the Ship Inn on Southbank. A very nice venue, as you can see from our feature image. The small picture below also shows where we had our breaks and meals – very refreshing to be able to spend break times (and evening meals) outside, compared to the recent Hub symposium held in Melbourne where we needed to be inside away from the cold Melbourne air!

Gerry Docherty organised this event, which ran over two days and consisted of a number of talks on the first day, as well as talks and discussion time on the second day. You can see the full programme here.

I gave the keynote on the first day, talking about social and regional variation in Australian Englishes (Aboriginal English and mainstream Australian English). I began by giving some definition of sociophonetics to set the scene. Citing the title of a paper by Paul Foulkes (2010) I pointed out it has been said to have “[a] long past, but a short history”. Sociophonetics draws on some very early traditions in linguistics, but the field itself has only had the name since around the 1970s. I recommend reading the Foulkes paper on this to learn more (open access). I also talked about how sociophonetic research is all about “[t]he integration of the techniques, principles and theoretical frameworks of phonetics with those of sociolinguistics” (Foulkes & Hay, 2015:292), and involves the social patterning of speech variants.

I also spoke about what I love about the field – in particular :

From a perception point of view, I love how people can listen to the same stimuli but classify them differently depending on their experiences. Also interesting – the judgements people bring can shape (or cloud) how they listen.

From a production point of view, I love how people can consciously (or inadvertently) signal things about themselves/ about their group membership(s), via fine-grained phonetic detail, and that listeners can also read these cues.

I went on to give some examples of sociophonetic studies run in Germany by Jannedy & Weirich (2014) and Weirich, Jannedy & Schüppenhauer (2020) which get at the heart of this (both papers are open access). I then spoke specifically about three studies I have been doing on Australian Englishes, in the area of perception of vowels, as well as two studies on speech production (voice quality, and consonant production). These studies are all due to be published soon and we will post updates when that happens, linking in with relevance to forensics.

Speaking of forensics, on the second day of the conference Helen gave a Hub talk called Forensic Transcription: Raising new questions for sociophonetic research. She introduced the work of the Hub to the group, made connections between forensics and sociophonetics, and talked about the research we have been doing in the Hub to develop more reliable ways of transcribing indistinct forensic audio. In the talk, and the conference more generally, Helen pointed out the necessity of sharing with the wider community what is possible when it comes to the perception and transcription of audio, and what is not possible. Debunking myths is vital when it come to forensics, because misinformation can have serious conequences for justice.

There were many other interesting talks at the conference as well (evident via the programme link provided above). A snapshot of examples are talks by:

- Gia Hurring from Canterbury NZ who talked about vowel variation in the Gloriavale Christian community (her Masters thesis is available here);

- Felicity Cox from Macquarie about her work modelling the dynamic features of diphthongs over 50 years (she dazzled us with some nice animations!);

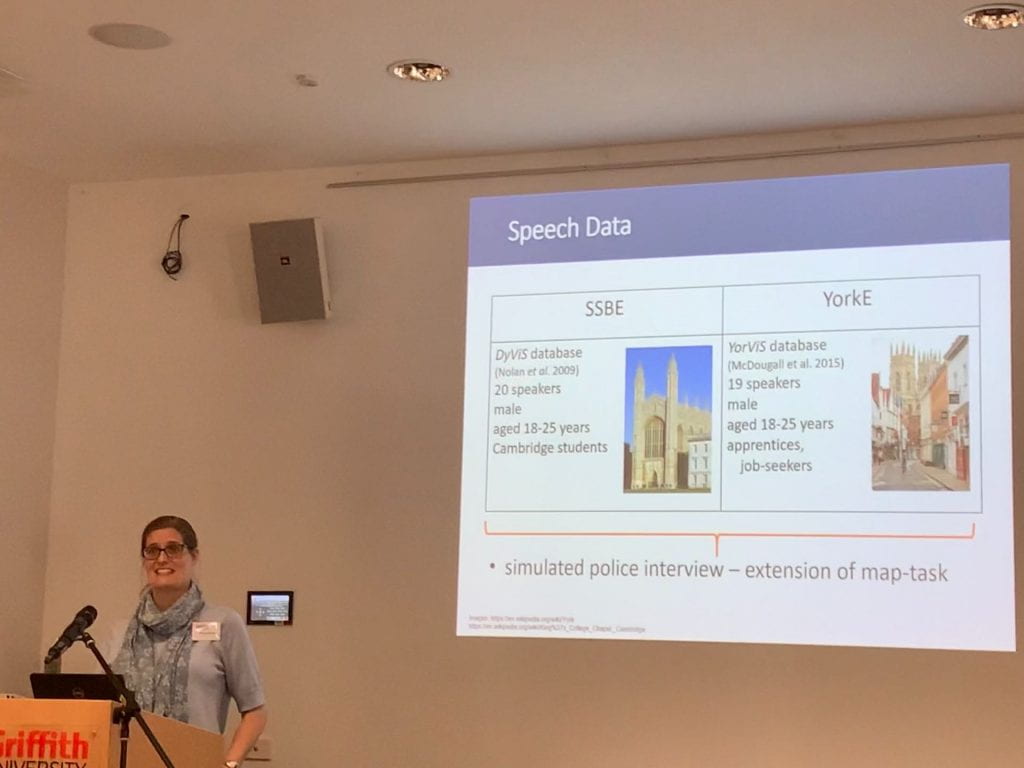

- Kirsty McDougall from Cambridge (as well as Martin Duckworth) who talked about disfluencies across different accents, looking at Standard Southern British English, York English, and Australian English. She found some very interesting differences between what the British groups did compared to the Australians, but cautioned that she still needs to tease apart some potentially confounding factors. McDougall and Duckworth (2018) have published previously on the topic of disfluencies and forensics (note this paper is not open access).

We hope to continue making connections with sociophonetics, and sociophonetics colleagues, for the work we are doing in the Research Hub for Language in Forensic Evidence. For those wanting to know more, you could also read the recent paper by Hughes and Wormald (2020) called Sharing innovative methods, data and knowledge across sociophonetics and forensic speech science. The author version of this work is available here.

In all, SocioPhonAus3 was a real delight, giving us the opportunity to share our work and consider future possibilities.

References

Foulkes, P. (2010). Exploring social-indexical knowledge: A long past but a short history. Laboratory Phonology, 1(1), 5–39.

Foulkes, P. and J. Hay. (2015). The emergence of sociophonetic structure. In Brian Mac-Whinney & William O’Grady (eds.), The handbook of language emergence, 292–313. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hughes, V. and J. Wormald. Sharing innovative methods, data and knowledge across sociophonetics and forensic speech science. Linguistics Vanguard, 6, no. s1, pp. 20180062.

Jannedy, S. and M. Weirich (2014). Sound change in an urban setting: Category instability of the palatal fricative in Berlin. Laboratory Phonology, 5, 91–122.

McDougall, K. and M. Duckworth (2018). Individual Patterns of Disfluency Across Speaking Styles: A Forensic Phonetic Investigation of Standard Southern British English. International Journal of Speech, Language and the Law 25.2: 205-230.

Weirich, M., Stefanie Jannedy and G. Schüppenhauer (2020). The social meaning of contextualized sibilant alternations in Berlin German. Frontiers in Psychology, 11: 1-18 (Article 566174).