A tale of two Luciles and two composers: Grétry père et fille

Early print editions of French music of the 17th and 18th centuries, especially opera, are a collection-strength of Rare Music at The University of Melbourne. One of the composers best represented is André-Ernest-Modeste Grétry (1741–1813; born Liège, Belgium) who was supremely successful in Paris as a composer of opéras comiques and recitative comedies in the decades before the French Revolution. Rare Music has early imprints of fifteen of Grétry’s stage works.

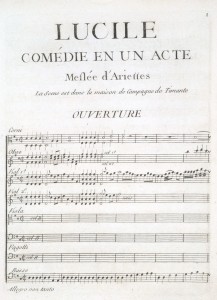

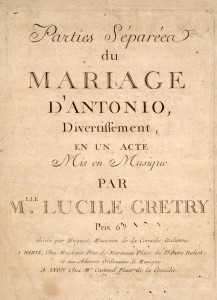

A casual glance at two particular Grétry light operas from the collection can cause confusion. There is A-E-M Grétry’s “comédie” Lucile, first performed in 1769, and Lucile Grétry’s Le mariage d’Antonio of 1786. Lucile is both the fictitious (and eponymous) heroine of Grétry’s comic opera (with libretto by Jean-François Marmontel) and the name his daughter—also a composer—was known by. Her given names were Angélique-Dorothée-Louise. The stories of the fictitious Lucile and the young Lucile Grétry are, in different ways, remarkable.

Fundamental to the fictitious Lucile’s story in the opera is the trope of the swapped baby. [1] When the daughter of a wealthy family, the original baby Lucile, dies in the care of a wet nurse, the servant substitutes her own daughter. With the action set on the substitute Lucile’s wedding day, her humble origins are revealed to her by her birth father (Blaise) and it seems that marriage is now out of the question. By the opera’s end Lucile’s personal qualities transcend her “class” and the happy pair marry after all.

Lucile Grétry, sadly, was denied the happy ending of her namesake. Her own brief marriage was unsuccessful and she died of tuberculosis at the age of 17.

As a young child Lucile received training in composition both from her father (in counterpoint and declamation) and other musicians. She began Le marriage d’Antonio when she was only 13 years old, writing all the vocal parts and, to accompany, a part for harp and a bass line. Lucile’s choice of the harp is emblematic as “for feminine decency, no instrument could compete with the harp” in Paris at the time. [2] Her father’s contribution to the opera was to arrange the harp part for full orchestra, making theatrical performance possible. He also made some alterations to the ensemble numbers. Le mariage was very well received by critics and audiences and stayed in the repertory for 5 years and 47 performances.

The man behind these two Luciles, A-E-M Grétry, was himself exceptional for his day in his attitude to women. Grétry took only 4 music pupils during his life and 3 were women. Through his copious writings, [3] he championed the creativity of women proclaiming that they could possess genius in any sphere. A musical career was singled out as achievable for many women and one that would offer them a welcome path to independence. Grétry characterised his daughter Lucile as an “image of feminine sensitivity and genius, coupled with a strong will to compose”. [4]

Grétry believed in the centrality of family life, [5] and this was celebrated in the greatest success of his opera Lucile, the quartet from scene 4, “Où peut-on être mieux qu’au sein de sa famille” (Where can one be so happy as with one’s family). Though suffused with sentimentality, it takes on poignancy in the knowledge that not only Lucile but Grétry’s other two daughters died young from tuberculosis.

Jennifer Hill, Music Curator

[1] For a synopsis see Robert Ignatius Letellier, Opera-comique: A sourcebook (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2010) p. 368–369.

[2] Jacqueline Letzter and Robert Adelson, Women writing opera: Creativity and controversy in the age of the French Revolution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), p. 49.

[3] See, for example, Grétry’s Mémoires, ou Essais sur la musique, written first as one volume in 1789, then enlarged to three.

[4] Letzter and Adelson, p. 25, 55–56.

[5] David Charlton, “Grétry, André-Ernest-Modeste” in Oxford Music Online, accessed 21 April 2016.

Categories

Leave a Reply