Revolutionary printing: money!

In 2016 we celebrate 50 years of decimal currency and innovations in paper money such as the next generation five dollar note. In Australia before the unifying advent of Federation which occurred in 1901, currency was a more chaotic affair. Banknotes represent a nation’s economic stability and during times of war and upheaval, these crises are likewise reflected in the currency. To show both students of printmaking and financial studies, the rich links between printing and economic history, the Baillieu Library Print Collection has acquired three engraved banknotes.

French Revolution banknotes

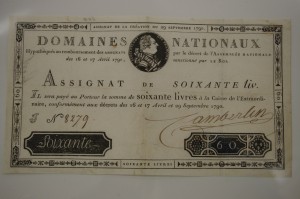

A variety of currency which arose and fell with the French Revolution was the assignat which were only printed between 1789 and 1795. Rather than having a value assigned to silver or gold, this engraved note was instead assigned to a value of land and was interest bearing. The Domaines Nationaux (1789-93) was an organisation established from the sale of the church lands, land which became the financial basis for assignats. Controlled by the National Assembly it was responsible for printing assignats and for their circulation in France. Louis XVI is featured on the note, and would remain there until his deposition when his portrait was replaced by the cap of liberty. The acquired note also features the signature of Camberlain, a representative for La Caisse de l’Extraordinaire, a department formed to issue assignats and combat their forgery.

Forgery

A British government sanctioned scheme saw economic warfare unleashed when British artists and other individuals flooded the French economy with forged assignats. These forged notes were intended to further ruin the financial stability of the French nation.[1] By 1795 an assignat was virtually worthless and they were withdrawn from use.

The British authorities showed no leniency towards its own citizens who forged the nation’s currency, however. To be found in possession of a forged banknote was a crime punishable by hanging. Forgery was not always an act of war; it was most often the crime of destitute men, women and children. In 1819 the artist George Cruikshank (1792-1878) was so disturbed by the sight of the hanged forgers wreathing the walls of Newgate prison, that he designed what is commonly referred to as the hanging note . [2] This note was influential in drawing attention to the overly harsh punishment which brought about reform and the lesser punishment for forgery offences: deportation to the penal colony of Australia.

Australian Pre-Federation banknotes

Many of the convicts sent to Australia were forgers, such as Joseph Lycett (born c. 1794). Lycett produced important colonial works of art including the book Views in Australia (1825) which is a highlight of the Rare Books collection.[3] However, he was also forging colonial banknotes: ‘unfortunately for the world as well as himself [Lycett] had obtained sufficient knowledge of the graphic art to aid him in the practice of deception, in which he has outdone most of his predecessors’.[4] Due to a shortage of British coins, a system of promissory notes, (which functioned somewhat like a cheque) was being used in the colony. Given that the history of banknote production and that of forgery occur concurrently, printing had to evolve, and so banknotes feature very sophisticated artistry and printing techniques.

Unlike present day Australian banknotes which are a uniform set carefully overseen by the Reserve Bank of Australia, before Federation any bank could issue paper currency and all of the states colonies were printing their own notes. Not surprisingly this cornucopia of paper money was an inefficient system.

Lycett, like many other forgers, was using a copper plate to produce clever imitations. As the uncirculated Bank of Australasia five pound note states in the inscription by the lower margin, it was produced with a patent hardened steel plate by Perkins, Bacon & Co. Jacob Perkins (1766-1849) pioneered new printing innovations including one he called ‘siderography’ which is to engrave on steel. This method enabled thousands of identical complex designs to be printed from a superior metal plate and was extremely difficult to copy. Engraving on steel would be one of the products born of the Industrial Revolution.[5]

A great leap in the complexity and visual appeal is evident in the Bank of Victoria one pound colour trial specimen, which depicts that colony’s namesake: Queen Victoria. Several artists and equipment would have been utilised to produce this sophisticated banknote. Unlike the previous two notes, this specimen is printed on both sides, an innovation which thwarted many forgers. The verso shows a guilloche, or an intricate repeated design which is produced by a lathe. A tool called a stump engraver would have been used to print the word ‘one pound’ repeatedly. These features, together with the use of multiple colour plates form an almost impenetrable security system.

By the 1890s in Australia, approximately 64 banks were trading before a crisis in 1893 which saw many of them close. By 1910 British pounds were no longer the nation’s currency and promissory notes were not legal tender.

Kerrianne Stone (Curator, Prints)

References

[1] Peter Bower, ‘Economic warfare: banknote forgery as a deliberate weapon’ in The banker’s art: studies in paper money edited by Virginia Hewitt. London: British Museum, 1995, pp.46-64

[2] The story of paper money by Yash Beresiner and Colin Narbeth, Wren publishing Melbourne, 1973, pp 23-26

[3] Joseph Lycett, Views in Australia, or, New South Wales & Van Diemen’s Land delineated: in fifty views with descriptive letter press, London: J. Souter, 1824-[1825]

[4] From the Sydney Gazette 1815 quoted in Printed images in colonial Australia 1801-1901 by Roger Butler, Canberra : National Gallery of Australia, c2007, p. 51

[5] See Gary W. Granzow, Line engraved security printing: the methods of Perkins Bacon ,1790-1935; banknotes and postage stamps, London: Royal Philatelic Society London, 2012

Categories

- Uncategorised

- Prints

Leave a Reply