Wombat, wombach, whom-batt wonder: early scientific ‘trafficking’ of marsupalia to Europe

The unique fauna of Australia intrigued, bemused and excited the imagination of their European ‘discovers’ from the moment of the first animal sightings in the late 18th century. One of these puzzling oddities was the wombat, which was described as a type of bear or a badger by northern naturalists grappling to classify the strange animal within existing scientific taxonomies, and said to taste of ‘tough mutton’ by sailors eager to sample fresh meat after many months at sea.

The unique fauna of Australia intrigued, bemused and excited the imagination of their European ‘discovers’ from the moment of the first animal sightings in the late 18th century. One of these puzzling oddities was the wombat, which was described as a type of bear or a badger by northern naturalists grappling to classify the strange animal within existing scientific taxonomies, and said to taste of ‘tough mutton’ by sailors eager to sample fresh meat after many months at sea.

The nocturnal and retiring habits of the wombat appear to have protected it from the notice of the expeditionary voyages of James Cook, and the exploration parties associated with the first settlers. Indeed it was almost a decade after settlement before the first wombat was sighted (February 1797), shortly ahead of the platypus (November 1797), koala (January 1798) and Tasmanian tiger (1805), though all were preceded by the discovery of the echidna (1792). The earliest description of a kangaroo (or more precisely a wallaby) was made in Francois Pelsaert‘s 1629 account of the shipwrecked Batavia, though this report seems to have been unknown to Cook, who remarks on a kind of jumping ‘grey hound’ in his Endeavour journal of 24 June 1770.

As a group these strange pouched and egg-laying creatures presented a distinct challenge to European classifiers, as articulated by James Edward Smith (1759-1828), founder of the Linnean Society:

When [one] first enters on the investigation of so remote a country as New Holland, he finds himself as it were in a new world. He can scarcely meet with any fixed points from whence to draw his analogies.

The first transported wombat

If you should ever find yourself in Newcastle upon Tyne, visit if you can the Great Northern Museum of natural history and archaeology, and utter a friendly ‘wombat-cough’ to a well-connected and well-travelled 218 year old stuffed Tasmanian wombat, the first specimen to be transported from Australia to Europe.

After several wombat sightings in 1797, a live female specimen was captured on Cape Barren Island (Bass Strait) in March 1798 by a party of British naval officers (including a young Matthew Flinders). The creature was taken by ship to Sydney and presented to amateur naturalist and Governor of New South Wales, John Hunter, where the ill-fated marsupial died after six weeks in captivity. Hunter wrote of the unfortunate animal:

After several wombat sightings in 1797, a live female specimen was captured on Cape Barren Island (Bass Strait) in March 1798 by a party of British naval officers (including a young Matthew Flinders). The creature was taken by ship to Sydney and presented to amateur naturalist and Governor of New South Wales, John Hunter, where the ill-fated marsupial died after six weeks in captivity. Hunter wrote of the unfortunate animal:

it was exceedingly weak when it arrived, as it had, during its confinement on board, refused every kind of sustenance, except a small quantity of boiled rice, which was forced down its throat.

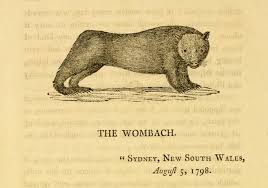

Not wanting to let the opportunity for scientific research lapse, Hunter had the corpse preserved in alcohol and shipped to his friend Sir Joseph Banks (President of the Royal Society) in London for more detailed taxonomic examination. In 1799 the soused specimen was barrelled onwards to the Literary and Philosophical Society in Newcastle (of which Hunter was a corresponding member), but not before the cask broke open, almost suffocating its carrier in ‘pungent and foul-smelling spirits’. There Thomas Bewick prepared an engraving of the wombat (based on an original drawing by Hunter) which was printed in the fourth edition of his A general history of quadrupeds (1800), becoming the first published illustration of the animal.

The ‘traffic’ in wombat specimens

From the early 1800s an increasing number of preserved wombats were shipped to Europe for dissemination amongst scientific circles. Several other wombat pioneers found themselves unwitting live specimens, who were met with wonder and curiosity on disembarkation. These included a wombat collected by the Scottish botanist Robert Brown (1773-1858) which he passed over to his friend, British surgeon and anatomist Everard Home (1756-1832), under whose watchful guardianship it lived cheerfully for two years:

It was not wanting in intelligence, and appeared attached to those to whom it was accustomed, and who were kind to it. When it saw them, it would put up its fore paws on the knee, and when taken up would sleep in the lap. [1808]

The British were not the only nation with a thirst for scientific discovery, and the rival Pacific expeditions of the French also resulted in the capture and repatriation of marsupial specimens. Three live wombats collected on the voyages of the Geographe and the Naturaliste commanded by Nicholas Baudin survived to arrive in France in 1803, at least one of which may have become the pet of Empress Josephine at Château de Malmaison.

A recent acquisition: Etienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire’s natural history studies, 1834-1835

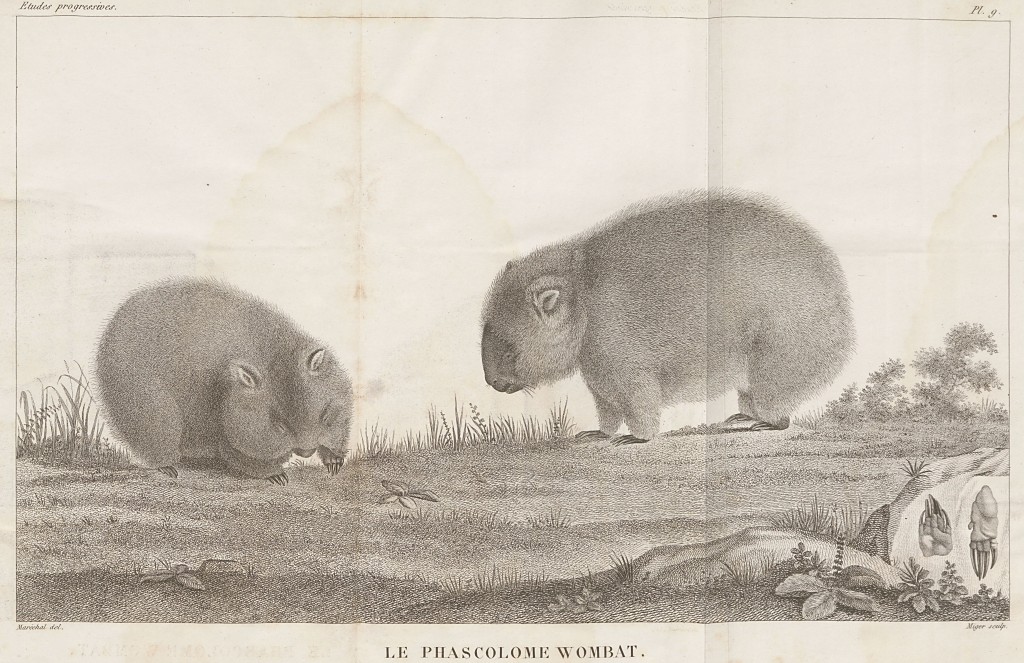

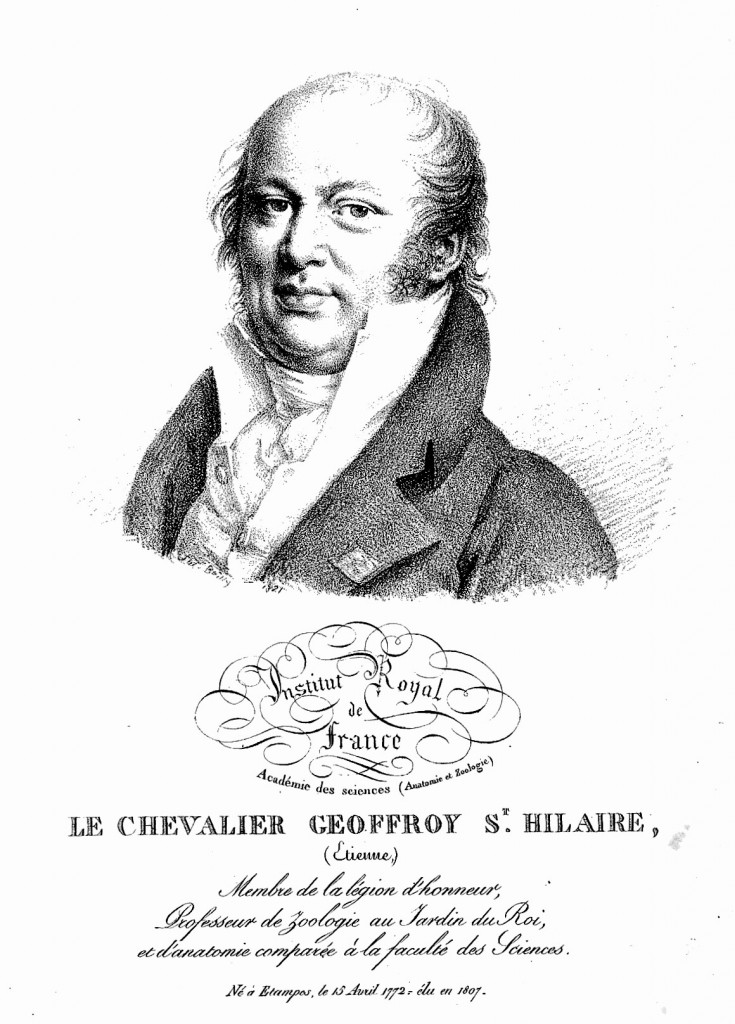

The Baillieu Library is fortunate to have recently acquired a copy of the 1834-1835 published studies of the distinguished French naturalist Etienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (1772-1844). The volume includes two detailed papers on the platypus and echidna, and a skilfully rendered fold-out illustration of pair of wombats placed in a naturalistic setting. As director of the Natural History Museum in Paris, Geoffroy was also administrator of the former Royal Menagerie, which had been relocated to the Jardin des Plantes after the French Revolution. Here he could observe at first hand exotic animals which had been collected from a variety of sources, many of them previously held in private hands. One of the more grisly directives following the 1789 revolution was that all exotic pets had to be turned over live to the former royal collection, or otherwise killed and given to the Jardin des Plantes for scientific studies, such as Geoffroy’s. It seems that our two ‘French’ wombats were amongst the lucky survivors.

Susan Thomas, Rare Books Curator

Bibliography and further reading:

Australian Broadcasting Commission. ‘The wombat boy’, Australian Story Program Archives, 25 March 2002 http://www.abc.net.au/austory/archives/2002/05_AustoryArchives2002Idx_Monday25March2002.htm

Cowley, Des & Brian Hubber. ‘Distinct creation: early European images of Australian animals’, The LaTrobe journal, no.66, Spring 2000, pp. 3-32.

‘The first wombat to leave Australia’ http://pickle.nine.com.au/2016/09/15/11/33/first-wombat-to-leave-australia

Flinders, Matthew. A voyage to Terra Australis undertaken for the purpose of completing the discovery of that vast country, and prosecuted in the years 1801, 1802 and 1803… Volume 1. London: Printed by W. Bulmer and Co., and published by G. and W. Nicol, 1814.

Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, Etienne. Etudes progressives d’un naturaliste pendant les années 1834 et 1835 : faisant suite a ses publications dans les 42 volumes des mémoires et annales du Museum d’Historie Naturelle. Paris: Chez Roret, 1835.

Pigott, L.J. & Jessop, L. ‘The governor’s wombat: early history of an Australian marsupial’, Archives of Natural History, v. 34, 2007, pp. 207-218.

‘The tale of a wombat: a journey from Australia to Newcastle upon Tyne’, The Guardian, 30 December 2013 https://www.theguardian.com/science/animal-magic/2013/dec/30/wombat-australia-to-newcastle-upon-tyne

Woodford, James. The secret life of wombats. Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2001.

Leave a Reply