A not-so-familiar Father Christmas: A Merry Christmas Polka from 1847

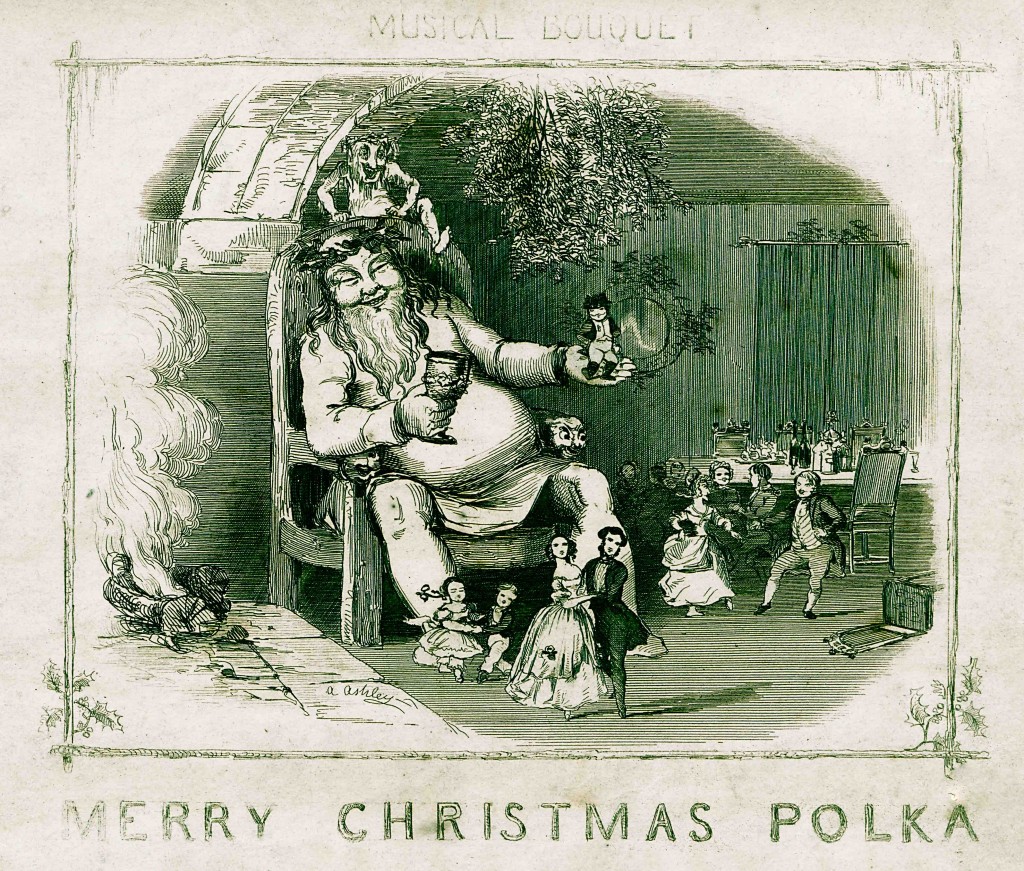

Looking at Christmas music in the Rare Music collection from Victorian-era Britain, I was surprised to see an unfamiliar Father Christmas-figure—a grinning giant—at the head of a very worn copy of the sheet music of a Merry Christmas Polka from 1847. I had expected to find a Santa in a fur-edged coat and hat, with a stout pair of boots and, perhaps, a fir tree over one shoulder; what I found (here rendered in green for festive effect!) was rather different.

Just ten years into Queen Victoria’s reign is a little soon for that particular Santa to be ubiquitous. After some general reading, I discovered that other illustrators depicting Father Christmas in the 1840s use graphic elements similar to those employed by the illustrator for this piece of festive sheet music, Alfred Ashley (1820-1897). 1) The holly wreath (instead of the hat) was common then as was the raised goblet. And Ashley’s Santa has “companions” from folklore, something not unknown in the 1840s. Here a goblin-like figure pulls himself over the top of the chair and what must surely be a leprechaun dances on his outstretched hand. The element of fantasy is something often found in Victorian-era illustration in, for example, the well-established genre of fairy painting. 2) Ashley’s Father Christmas is remarkably plainly dressed, in a non-descript smock, barelegged and with no apparent footwear, but he is toasting himself by a roaring fire: a yule log perhaps? The suspended mistletoe and profusion of food and drink (here just visible on the table) are other Christmas traditions in the illustration that have stood the test of time.

Engraved illustrations were increasingly common on sheet music in the 1840s and no doubt a significant incentive to purchase. Pianos, including compact cottage (upright) pianos for home use, were luxury goods, but were owned by the well-heeled middle and upper classes in increasing numbers. 3) It is these people—particular the fashionably dressed family in the foreground—who are depicted in the illustration, dancing at home, as was then a custom. And this polka, a couples dance distinguished by a hopping step, coincides with the early years of “polkamania” in Britain. 4) With its regular repeated 8 bar phrases, this is definitely a polka written for dancing rather than listening to. To hear the distinctive polka rhythm, and to get a sense of what these simple piano dances written for domestic use were like, please listen to short excerpts from the Merry Christmas Polka Finale below—the “big finish” is a very clear signal to the dancers that the music, and the dance, is nearing its end.

With best wishes for the Festive Season from all at Special Collections.

Jennifer Hill, Rare Music Curator

- This is no. 113 of the Musical Bouquet series; the composer is not named. The publisher, active from 1845 to 1917, went on to issue at least 8106 numbers, producing one, then two per week. The website http://www.musicalbouquet.co.uk/ is an excellent source of information and devotes a page to Alfred Ashley, with many examples of his work.

- David Wootton, The illustrators: the British art of illustration, 1800-1999 (London: Chris Beetles, 1999), p. 21-28.

- Derek Scott, The singing bourgeois: songs of the Victorian drawing room and parlour (Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1989), p. 45-49, 54.

- See Gracian Černušák, Andrew Lamb and John Tyrrell, “Polka” in Grove Music Online.

Leave a Reply