A Ride to Heaven or to Hell? A new Dutch broadsheet in the Baillieu Library’s collection

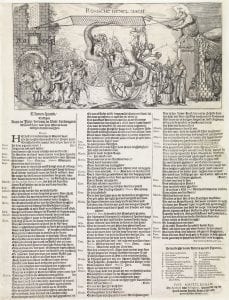

A bizarre wagon surmounted by a seven-headed beast makes its way across the centre of a tumultuous image. The grotesque central motif of this 1621 broadsheet must have lured the reader to look at its bizarre details and to personally read the text below, or to listen to someone else read it aloud. Viewers of the time would immediately have associated this scene with the seven-headed beast of the Apocalypse in the New Testament Book of Revelation, and have understood that this was a work of political and religious propaganda.

As the title tells us in a sly piece of satire, this is a Roman (ie. Catholic) version of a “ride to Heaven”. It is a satirical title because the passengers will all, in fact, find themselves delivered into the doorway to Hell overseen by the monstrous figure of Lucifer. The text below purports to record a three-way discussion outside a print shop, offering a commentary on many of the figures in the scene. A key with letters at the end of text offers further help in decoding each satirical allusion. The broadsheet was produced in the context of bitter battles between Protestants and Catholics in Europe, and in particular Protestant Dutch animosity to Spanish Catholics during the intermittent Dutch Revolt, which took on new vigour in 1621. It appeared with a publisher named as Antoni van Salinghen in Amsterdam; the heart of the de facto independent northern Netherlands and also a major printing centre.

This work of religious and political propaganda plays upon the classical tradition of the triumphal wagon. Rather than a glorious scene of military victory, here the Pope, the Holy Roman Emperor and the Spanish king – as a key at the bottom of the text confirms – are foolishly riding a diabolical wagon. Jesuits and other religious figures are presented in negative guise, amplifying the anti-Catholic message of the image. The ghost of the Duke of Alba, here named also “Tyranny”, is singled out for special mention (letter L). He is depicted cannibalistically devouring a child and recalling for viewers his role at the head of Spanish forces in the 16th century.

Broadsheets like this were designed to grab the public imagination, and they appeared in great numbers in the 16th and 17th centuries. Since the mid fifteenth-century, with the development of moveable type and easier access to paper, there had been an explosion in the number of printed books, pamphlets and broadsheets that circulated across Europe. Johannes Gutenberg’s ground-breaking Bible printed in Mainz in the 1450s set this in motion, and the Baillieu library holds one precious leaf of his masterpiece of early printing.

Broadsheets, by comparison, were designed to be cheaply printed on single pieces of paper, and were much less elevated examples of early modern print culture. This makes them fascinating windows on the concerns, anxieties, fashions and latest events in early modern Europe. By 1621, when this publication was produced, access to print was a regular part of life for many Europeans: whether personally owned or accessed in a tavern or market place. Broadsheet texts often rhymed and were frequently read or sung out loud in public settings. Many were also illustrated with eye-catching images, often rapidly made by printmakers who knew how to attract the eye of a passer-by and complement the lively text.

The popularity and relative inexpensiveness of broadsheets at the time of their production makes them paradoxically rare today, as they were rarely saved. In Australia, we have relatively few early modern broadsheets. The collectors who put together the wonderful print and rare book collections that we have in Australia often acquired finely-crafted prints by well-known master artists like Albrecht Dürer or Marcantonio Raimondi, as well as high-quality books long valued by bibliophiles. Students and researchers are more likely to see an Albrecht Dürer print up close than a more crudely-made broadsheet like this. Its presence will therefore enrich the collections-driven and object-based learning activities that are a feature of teaching in History at the University of Melbourne.

We are fortunate that objects like this broadsheet are also now being acquired for Australian collections. They broaden our understanding of how politicised print culture was in the early modern world, and provide a window onto outrageous political propaganda, in which an emperor or pope could be mocked, and print culture formed a vital tool for attacking enemies.

By Dr Jenny Spinks.

*****

Jenny Spinks is Hansen Senior Lecturer in History at the University of Melbourne. She teaches the history of early modern Europe, with a particular interest in print culture, in and object-based learning. Her publications include a recent collaborative article with Lyndal Roper on the first piece of printed propaganda for the Reformation, produced over a hundred years’ earlier in 1519, and also depicting a wagon ride to Hell.

Leave a Reply