What changes? What makes an artist?

Diana Tay

For a conservator, troubles begin, as troubles often do, in a collection, a museum or perhaps, in an archive. Materials change, degrade and then, comes the worry that we’ll lose a piece of history or a moment in time. However, the powers of digitisation have made many collections accessible today in what appears to be a visual freezing of time. In fact, as in fiction, this desire has continued for as long as collections continue to grow – our desire to have and to hold for as long as possible[i]. As an unsuspecting conservator browsing thorough DAUB (1949)[ii], a student art magazine by the National Gallery Art School, I found that it set off these reflections on time and artists. The materiality of time was evident in the thirty yellowed pages of drawings and articles printed in monochrome blue ink. Working with contemporary artists as part of my profession but recalling the saying that reading a book is like looking into someone’s mind, I found myself exploring how these student writings, particularly the more humourous or ironic notes and cartoons in the magazine, resonate nearly seventy years later.

People have the quaintest ideas about artists, and ask the most amazing questions, such as “Is it a gift or did you learn?” or (in hushed tones): “Are you an artist?”

— How to paint in six easy lessons or how to be happy tho’ poor

What makes an artist? A witty banter peppered with sarcasm, Betty Quelhurst writes about the six stages of how to approach a painting by playing on how to navigate the general perception of artists – from developing an ‘arty look’ (in which letting your hair grow is necessary); picking up a bohemian accent; acquiring a brass plate with ARTIST displayed in prominent letters (Fig. 1); and of course, getting your painting framed so it may increase in price. Who would guess that the mischievous Betty Quelhurst had just served for four years in the Air Force during World War Two (1939 – 1945)?

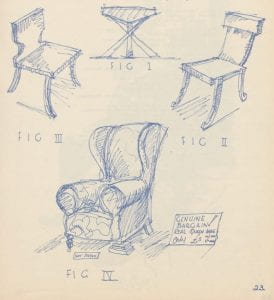

So to be an artist in 1949, you needed wit or perhaps, to be tongue in cheek about your profession. Geoff Saphin saw these young artists ‘living in an age of speed’ and his own desire for progression was evident in a playful commentary (p.23) on the subject of seating. His idea of “good taste” is accompanied by a sketch of four chairs (see Fig. 2) – a reference to the artist stools used for outdoor sketching (which, apparently traces back to 4000 BC) – suggesting it was necessary to dress accordingly. The bargain price for the right chair of his time was a comfortable vintage from a baronial mansion suggesting a degree of laziness or faded glory in his fellow students. Written 70 years ago, there is also some irony in reading about ‘admiring the past without coveting it’, as he laments, ‘Migosh, imagine the girls of today trying to board a crowded tram dressed in the fashions of 50 years ago.’ Such a reference to 1920s fashion seems to suggest a sentiment that saw the past as something obsolete and unbefitting. But with the 1970s in fashion today (think flares, platforms and active wear), and with our penchant for vintage items, why do we find ourselves looking back rather than forward as these young artists were?

Without a doubt, digitisation can make the past accessible to a wider audience, while reducing the risks of damage through physical contact with the object.

And if this post piques your curiosity about these self-conscious reckonings of the young artist, I’d suggest accessing the archive and reading the article, ‘WHY’ (p.19) written by its foremost collector, Lucy Kerley. What makes an artist? Perhaps, it will keep changing, or perhaps as the cartoon below suggests, a cavalier attitude and the anonymity of a sketch does have some value in freezing a puzzling moment in time.

[i] Storr, Robert. “To Have and to Hold.” In Collecting the New: Museums and Contemporary Art, edited by Altshuler Bruce, 29-40. Princeton University Press, 2005.

[ii] University of Melbourne Archives, & Kerley, L. (1949). Daub, 2007.0060.00152.

Leave a Reply