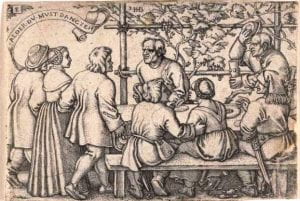

The peasants’ feast by Sebald Beham

The mid-16th century, marked by the beginning of the Protestant Reformation, was a challenging time for artists working in northern Europe. In January 1525, only 7 years after Martin Luther had nailed his 95 theses onto the door of a chapel in Wittenberg and thereby setting in motion the Protestant Reformation, three artists; the brothers Sebald and Barthel Beham, and Georg Pencz were trialled before the town council of Catholic Nuremberg. For months these ‘godless painters’ were banished from the city for claiming they did not believe in baptism, Christ or transubstantiation (the belief that bread and wine would become the physical body and blood of Christ at consecration) [1.].

Peasants’ feast belongs to the series The Country Wedding or The Twelve Months which was created by Sebald Beham in 1546 while he was living in Frankfurt [2.]. The Baillieu Library Print Collection currently holds 8 prints belonging to this series. In Peasants’ feast there are 8 peasants who gather around a simple wooden table to enjoy food and drink. Other works in this series portray amorous activities, drunkenness, dancing and brawls which represent peasant behaviour as excessive and vulgar, indeed the grape vine in the background of this work implies that there is an abundant supply of wine in the scene which is reinforced by the large cup the man on the right clutches. Beham’s use of line is heavy which gives the work a coarse aesthetic, furthermore the figures’ bodies are stocky and unrefined which makes their angular faces appear grotesque.

From the medieval period in northern Europe peasants had been represented as an amusingly uncouth underclass to the nobility. Stereotypical representations of peasants portrayed them as characters with poor manners and immoderate behaviour which was designed to contrast the chivalric moral standards upheld by the upper classes, and justify their sense of cultural superiority. During the Reformation these caricatures were used by middle class Lutherans to mock a percentage of the population who threatened their cultural values [3.]. In terms of adhering to this trope, or subverting it, Berham’s image responds to a variety of audiences.

The gazes of all the figures are self-contained within the work, they directly engage with one another and appear unconcerned by lofty metaphysical questions. Viewers are not invited to identify with particular figures, despite their idiosyncratic appearances, the peasants are represented as humorous figures rather than particular individuals. This lack of empathetic identification allows viewers to mock the lewdness of the lifestyle portrayed. However, the work cannot be read merely as an admonishment of lower class values. The representation of merry peasants within a fertile agrarian setting, may be read as a pleasant contrast to the increasingly repressive moral standards of Lutheranism. The lively gestures of figures combined with a confident use of line creates a playful, jovial atmosphere. In this way the work can be read as an idealisation of the naivety and looser moralities of peasants; a pastoral ideal.

The complexity of this image speaks of a wider debate surrounding moral values within Renaissance German society. There was a larger cultural debate which questioned the relevance of festivities as many moralists viewed them as profane [4.]. Luther wrote: “All festivals should be abolished and Sunday alone retained […] since the feast days are abused by drinking, gambling, loafing and all manner of sin” [5.]. In 1525, the same year the Beham was banished, Nuremberg abolished most of its Christian holidays [6.]. This festivity does involve ‘all manner of sin’; ‘drinking’ and ‘loafing’, however the quaint rural setting gives the print a charming quality. It is left to viewers to determine how they will read this work. Moreover, in Europe during the 16th century, printmaking was largely regarded as a lower art form and its mass producible quality meant that it was available to a broader audience. [7.] Beham was aware of public tastes which is why he transitioned from woodcuts to engravings after he moved to Frankfurt, the uncertain moral intent of the image meant that the work would have attracted a larger audience [8.].

Mary Henkel

Research Assistant Intern

References and further reading

[1.] Alison Stewart, “Sebald Beham: Entrepreneur, Printmaker, Painter” Faculty Publications and Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design, 2012, pp. 2-3.

[2.] Alison Stewart, “Beham Family” Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press, accessed May 15 2019, 2003, subscriber link.

[3.] Keith Moxey, “Sebald Beham’s Church Anniversary Holidays: Festive Peasants as Instruments of Repressive Humour” Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, vol. 12, 1981-82, pp. 127-130.

[4.] Alison Stewart, Before Bruegel: Sebald Beham and the Origins of the Peasant Festival Imagery, New York: Routledge, 2016, p. 279.

[5.] Martin Luther quoted in Luther’s Works, J Pelikan and H Lehmann (eds.), vol. 44, 1955, pp. 182-83

[6.] Moxey, 1981-82, p. 126

[7.] Moxey, 1981-82, p. 129

[8.] Stewart, 2016, p. 280

Leave a Reply