Making rare collections accessible: An interview with Lisa O’Sullivan

Special Collections and Grainger Museum Blogger, Ana Jacobsen, recently interviewed Dr. Lisa O’Sullivan to find out what the role of Program Manager, Outreach and Engagement at the University of Melbourne entailed. Lisa is a qualified historian who has also worked as a curator in London, New York and Australia.

What led you to the role of Program Manager, Engagement and Outreach at the University of Melbourne’s Cultural Collections and Archives?

I trained as a historian, but I never actually wanted to be an academic which is a bit unusual but some people do it for other reasons and I guess I was one of them. I worked as a curator in London for quite a while and then I ended up moving over into libraries and rare books, working in New York. I’ve been very lucky to have had an international career but I’m originally Australian and I wanted to come home. I love working with collections and telling stories about them – and I love helping other people tell stories about them. I also studied at the University of Melbourne, so I knew we had wonderful collections and it just made this role attractive on lots of levels.

What did you study when you were here?

I mostly did history and philosophy of science and then my doctorate was in straight history. But my science background means that I’m really interested in diverse collections and finding multidisciplinary ways of looking at them.

Do you find your role is particularly hybrid and overlaps with many other areas? Who do you see yourself collaborating with in the future to organise programs?

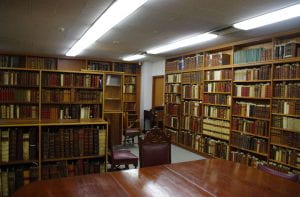

This role is going to be all about collaboration. There are over forty cultural collections in the university but I’m only directly working with the Special Collections held in the Baillieu Library and the Archives. My job is going to be to help facilitate as much conversation between different people as possible about how we use these collections in exciting and engaging ways. Teaching and learning is a massive aspect of this but there are also issues such as whether we want to engage public audiences and how we cultivate other kinds of student interactions with the collections and exhibitions.

When you visit galleries and museums, are you taking inspiration from their concepts, practices and procedures to adapt to your own programs?

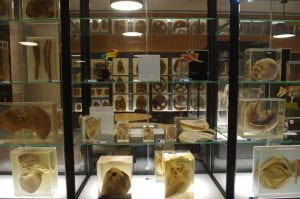

Definitely – I think there’s always a flow of influence between different spaces. I love what’s considered to be old-fashioned now. The curation I’m drawn to is not exactly like the Wunderkammer, but certainly embraces the idea of packing as many objects into an exhibition as possible. Especially in natural history, there’s this idea that you’re going to be able to learn from all these different taxonomies. There is a belief that you can learn directly from seeing all these objects in connection with each other, which I really love. I think it’s also about being open-minded and not going in to a gallery thinking that it can only show ‘gallery stuff’ or likewise, that natural history museums only do ‘natural history stuff’. It’s about looking at all of it and thinking what works well? The creativity can be in really unusual places.

Are there any museums and galleries, especially in Australia, that you’re particularly inspired by?

MONA is an obvious one and I think that it’s an interesting example of what can happen when you have a vision that’s not really constrained by finances or institutional factors. Having said that, I really love the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery because that’s a museum that has art, natural history and social historical collections and a very strong Indigenous presence. Getting those different elements to work together and making sense of them all under one roof is impressive.

Where would you say is doing this best in other parts of the world?

The Wellcome Collection, a free museum and library that I used to work with in London, has just opened a new permanent gallery called Being Human. The curators have mixed historical objects with contemporary art and have also specifically designed the exhibition to be completely accessible. Whether its people with mobility issues, or people who need tactile interaction, there’s a great sense of inclusivity in terms of content and accessibility for as many audiences as possible.

What issues or gaps do you recognise within engagement currently?

Generally, engagement tends to be very bespoke and I find that when you work with a focus group, which will be members of the community who are involved, you can sometimes end up developing a shared language that brings them more inhouse than they would’ve been if they’d just come to the exhibition. As a result, even with a focus group, there is a danger of losing sense of who your audience is. What you need to do is really put the time in and you have to give up a lot of control if you’re going to do engagement meaningfully. Take the answers you get as opposed to trying to get the answers you want. Engagement needs to be done on the terms of the community and if it takes a long time, you’ve just got to accept that. I think the challenge is that it’s often something that’s tacked on to a project that you’re just going to do as one more thing but if it’s going to be meaningful, it’s got to be answerable to the agenda of the people who are giving you their time and expertise. It’s a challenge!

Is there anything that you’ve been thinking about for a long time; like a dream that you have or a little project that you want to make happen?

I’d love to see a lot more students getting access to the archives and collections, finding an object that they resonate with and basing a project on that. I’m really fascinated by virtual learning and how to translate an interaction with a real object into a virtual teaching environment. Having numerous people interacting with an object can be so helpful in developing an understanding of its history from multiple perspectives. I really like it when a group looks at an object – say for example, a teacup – and one person will talk about its design, another will talk about the potting, the ceramics and how it was produced, and another will speak about the chemistry of clay. For me, it’s about trying to find ways to show people just how many different methods you can adopt to work with objects.

And leading on from that, encourage people to critically think about archiving and history?

That’s super important as well. We should question why the university has these collections. What was the thinking behind why they were brought together? How were they brought together? There are a lot of power relations embedded in that. What’s worth saving and why is it worth saving? If an object has different meanings to different groups, who has the moral authority to make that final decision? It’s a fascinating area!

What is the significance of ensuring engagement within a larger cultural context and how does it positively affect our society?

Being trained as a historian, I think it’s important that people have a more nuanced understanding of history. And material objects are a good way to help get that. Alice A. Proctor is an Australian based in Britain and she runs Uncomfortable Art Tours where she takes groups through major galleries and does postcolonial interpretations of the exhibitions. I think what’s so interesting about this is that she is just an individual – she can’t change what’s been hung, but she can help people appreciate it from a totally different perspective. It’s about having that diversity of voices to understand how these remnants of the past are meaningful in different ways for different people.

What is the most rewarding part of your job and what do you find fulfilling about it?

What I love is working with people who have this incredibly deep knowledge that I think is honestly impossible to get without working with a collection over a long period of time. It’s the fact that, almost as an aside, they’ll just show you this seemingly quite mundane object and tell you something extraordinary about it so that you eventually find it being your favourite thing. That gets me hooked. I love that enthusiasm about sharing knowledge.

What advice would you give to someone interested in working within program management, engagement and outreach? Where should they start to gain experience and what can they expect to get out of a career working in such a role?

This is the first time I’ve had a role with this exact title, but I’ve been doing this kind of work my whole career. The GLAM (Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums) sector is tough. Start by knowing what gets you excited because these are challenging roles and you must be able to juggle a lot of things at once. There’s always going to be backend administrative stuff that’s not always glamorous, so know what you like, because that’s going to help you a lot.

Ana Jacobsen

Special Collections and Grainger Museum Blogger

Ana is currently studying a Master of Creative Writing, Editing and Publishing.

Leave a Reply