A View from the Harbours of ‘White-only’ Australia: Captured for the Commercial Travellers’ Association

Dina Hussein is a PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne’s School of Historical and Philosophical Studies. Her thesis examines the indigenous working-class history of the Egyptian port city of Alexandria in the period between 1850 and 1919.

It is the 1930s in the southern coast of Western Australia, and a group of formally dressed men and women – travellers, settlers, white immigrants, or all the above – are looking out towards the ocean from the harbour. The unknown photographer captures them from behind, lined up facing the ocean next to a modern coach that is elegantly parked along the coast. We are looking at them, looking at the serene and scenic coastline unfolding into the horizon. But what do we actually see in this image? And how should we look at photographs capturing Australia’s colonial modernity?

Photographic images, as historian Jane Lydon eloquently describes, are no ‘transparent window into the world.’[1] Implicated in structures of power, representational biases, and exclusion (the violence of modernity), the photographic archive requires interrogation. The photographic collection of the Commercial Travellers’ Association of Victoria (CTA) is no exception.[2] In an attempt to interrogate a few photos in this archive, I briefly highlight their historical context and aspects of the images’ composition.[3]

Around ten years after its establishment in 1880, with a mission ‘to improve the conditions of commercial travellers,’[4] the CTA began publishing a monthly journal, The Australian Traveller, for its members in Australia and overseas.[5] In 1905, the CTA introduced a ‘high quality’ annual supplement, Australia To-Day – to promote the country’s industry and tourism.[6] With an expanded audience spanning the Commonwealth and beyond, Australia To-Day appeared to have been successful in its promotion of the official image of ‘Australia’. Based on the CTA’s Board Minutes, Dennis Byrans shows that the Prime Minister’s office placed an order of 2550 copies of the magazine’s 1950 issue for its Departments of Commerce and Information.[7]

The CTA issued its publications for 80 years, roughly between 1890 and 1976.[8] At the backdrop of this historical timeline was a brutal settler-colonial project, the devastation of the Indigenous population and the racist ‘white-only’ immigration policy.[9] The selective group of photographs I discuss here, however, are confined to the 1920s and 1930s. This was the period, as historian Anne Rees tells us, when Australians began embracing ‘modern technologies of motion with a fervour’.[10]Mobility, she argues, was the hallmark of Australia’s colonial modernity,[11] driven by a society of ‘displaced [white] settlers, anxious to conquer stolen land, accustomed to the departures of ships, and painfully conscious of their distance from each other and from “Home”.’[12] Within this historical context, I look at a few of the photographs that were most likely commissioned by the CTA for its annual magazine, specifically those capturing Australia’s harbours.

I initially approached the CTA’s photographic archive to see if the photos reflect themes of insularity and exclusion, which reverberate in the literature on the Australian city and society.[13] I chose to focus on harbours and waterfront settlements as they are often considered sites of coexistence; and points of entry and departure for immigrants. Indeed, this choice is confirmed by the fact that in the 1980s, ‘85 per cent of Australians lived within fifty kilometres of the ocean.’[14] My search for ‘harbour’ and related words – ‘port’, ‘dock’ and ‘ship’– yielded around 29 results of black and white photographs associated with the magazine, but with unknown photographers.[15] Around sixteen photos showcase Sydney Harbour – in a display of imperial technological progress celebrating the new ‘Bridge’ (such as Image 3) or as a site of water sports and leisure (such as Image 4). The centrality of the ship in such images, as a sign of the advent of progress and international modernity to the British province, is evident.

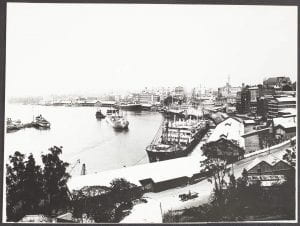

Photographs of Western Australia’s harbours overlooking the Indian Ocean portray a more sombre image (see, for example, images 2, 6 and 7).[17] In these photos, aerial views and long shot images capture the waterfront settlements, the harbour, the ships and the Indian Ocean at a distance, and they are taken from land at height– almost always from behind trees which are in the forefront of the images’ composition.[18] What are the trees hiding? The black smoke coming out of the vessels in the horizon (Image 6) ‘taints’ the more idyllic image of the settlement captured by the photo – simultaneously alluding to the cost and violence of modernity and industrialization, as well as the colonial condition that haunts the Australian city.

By way of comparison with international images, there is an overall absence of the hustle and bustle typical of port towns and docks; even in a close-up of the docks in Brisbane (Image 8), there seem to be no people, so that the conditions of labour and livelihood, or the arrival and departure of people and goods are invisibilised. But what can we speculate about this absence? What we know is that harbours in this archive reveal too little about the everyday reality of Australian waterfront communities and life at the docks (beyond the promotion of leisure or the prestige of Sydney Harbour for the tourists’ gaze). We can probably discern insularity and exclusion, as well as longing for the world that lies beyond the ocean – evident perhaps in the clustering of settlements around the harbour, at the edge of Australia, and gravitating towards the sea (Image 7). Yet, the images (shot at a distance from behind trees) hide more than they reveal about Australia That-Day. And perhaps that was precisely the intention.

The availability of such a digitised archive online, however, provides an opportunity for what Lydon describes as the ‘democratising’ of the photographic archive – by exposing ‘different ways of seeing’ it.[20] I echo her research premise by asking: how can these photos be seen and used differently from their intended purpose by contemporary Australians ‘of different cultural traditions’?[21]

[1] Jane Lydon, “Democratising the Photographic Archive,” in Sources and Methods in Histories of Colonialism: Approaching the Imperial Archive, ed. Fiona Paisley and Kirsty Reid (Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge, 2017), 18.

[2] The photographic collection of over 1000 images has been digitised by the University of Melbourne Archives. The photographs are now mostly available to view online, except for photos that remain in copyright, and photos of Indigenous people. I could locate only six entries of photographs featuring Indigenous people in over 1000 photographs of the CTA collection.

[3] Anna Pegler-Gordon’s approach to ‘seeing images in history’ through focusing on their historical context and composition influenced the way I tackled the photographs, see: Anna Pegler-Gordon, “Seeing Images in History,” Perspectives on History, published Feb 1, 2006, https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/february-2006/seeing-images-in-history

[4] Dennis Bryans, “Magazines a Specialty: The Specialty Press and the Commercial Travellers’ Association,” Bulletin of the Bibliographical Society of Australia and New Zealand 28, n0. 3 (2004): 4.

[5] Bryans, “Magazines a Specialty,” 14.

[6] Bryans, “Magazines a Specialty,” 4.

[7] Bryans, “Magazines a Speciality,” 16. For an excellent overview of the history and architecture of the CTA building in Melbourne’s Flinders Street, its prominence in the cityscape, in addition to the Association’s close ties with government officials during its heydays, see: Christopher Walker, “Goodbye Majestic, The Life and Death of the Commercial Travellers Association Building,” Transition, no. 54-55 (Jan 1997): 64-65.

[8] Bryans, “Magazines a Specialty”, 4.

[9] Keith Jacobs and Jeff Malpas, “Immigration, Indigeneity and Identity: Cosmopolitanism in Australia and New Zealand,” in Routledge Handbook of Cosmopolitanism Studies, ed. Gerald Delanty (New York: Routledge, 2012), 518-520.

[10] Anne Rees, “Reading Australian Modernity: Unsettled Settlers and Cultures of Mobility, History Compass, (2017): 5, doi: 10.1111/hic3.12429

[11] Rees, “Reading Australian Modernity,” 6.

[12] Rees, “Reading Australian Modernity,” 8.

[13] See, for example, Jacobs and Malpas’s study on cosmopolitanism in Australia and New Zealand in Keith Jacobs and Jeff Malpas, “Immigration, Indigeneity and Identity: Cosmopolitanism in Australia and New Zealand.” They present a compelling argument that cosmopolitanism, whether real or imagined, ‘has yet to take hold in … Australia,’ due to the persistent colonial condition that fosters structural inequalities. (p. 518). In her study of the Australian city, Emily Potter describes ‘endemic physical and psychic exclusions’ in the nation’s ‘imaginary and material space.’ in Emily Potter, “Contesting Imaginaries in the Australian City: Urban Planning, Public Storytelling and the Implications of Climate Change,” Urban Studies 57, no. 7, (2020): 1537, doi: 101.1177/0042098018821304.

[14]Rees, “Reading Australian Modernity,” 6.

[15] The metadata of the archive indicates that almost all the photographs yielded in the ‘harbour’ search were previously archived (or grouped) under Australia To-Day, which indicates the CTA most likely commissioned (or considered) them for the magazine.

[16] The catalogue description notes the following text written on verso: “W.A. Government. ‘Australia Today 1933”. This might indicate that the 1928 image was featured (re-used) in the magazine’s 1930 issue. It seems that the magazine’s editors have commonly reproduced old photographs for their issues. The mention of the W.A. Government requires further investigation – through possibly researching the issue in question to locate the articles (and other text) accompanying the photographs.

[17] I found five images of harbours in Western Australia, two in South Australia, five in Queensland, one in Tasmania and one of unknown location.

[18] Except one image titled, ‘Brisbane’s Dock at Circular quay’ (that provide a slightly closer capture of the docks – image 8) the remaining images in Queensland, South Australia and Tasmania reproduce the ‘scenic’ long shot perspective (akin to the Indian Ocean images) with the land at its highest point and the world (the ocean) far in the horizon.

[19] I have noticed that the catalogue description (often in lieu with previous archival references) includes text that ascribe date range for the images beyond the entry’s referenced date, for example “Scenic, 1929-1932,” is found in the description of this photograph. It is unclear what this date range indicates.

[20] Lydon, “Democratising the Photographic Archive,” 28.

[21] Lydon, “Democratising the Photographic Archive,” 28.

References

Bryans, Dennis. “Magazines a Specialty: The Specialty Press and the Commercial Travellers’

Association.” Bulletin of the Bibliographical Society of Australia and New Zealand 28, n0. 3 (2004): 4-23.

Jacobs, Keith and Jeff Malpas. “Immigration, Indigeneity and Identity: Cosmopolitanism in

Australia and New Zealand.” In Routledge Handbook of Cosmopolitanism Studies, edited by Gerald Delanty, 516-526. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Lydon, Jane. “Democratising the Photographic Archive.” In Sources and Methods in

Histories of Colonialism: Approaching the Imperial Archive, edited by Fiona Paisley and Kirsty Reid, 1-31. Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge, 2017.

Pegler-Gordon, Anna. “Seeing Images in History.” Perspectives on History. Published Feb 1, https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/february-2006/seeing-images-in-history

Potter, Emily. “Contesting Imaginaries in the Australian City: Urban Planning, Public

Storytelling and the Implications of Climate Change.” Urban Studies 57, no. 7, (2020): 1536-1552. doi: 101.1177/0042098018821304.

Rees, Anne. “Reading Australian Modernity: Unsettled Settlers and Cultures of Mobility.”

History Compass, (2017): 1-13. doi: 10.1111/hic3.12429.

Walker, Christopher. “Goodbye Majestic, The Life and Death of the Commercial Travellers

Leave a Reply