The Renaissance of early Greek maps

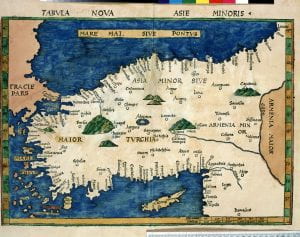

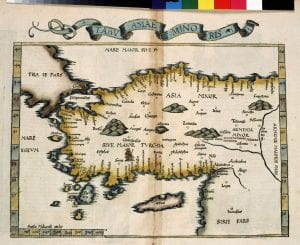

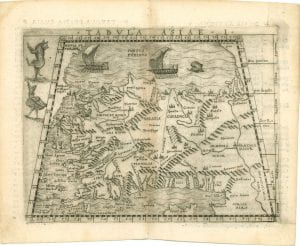

The University of Melbourne’s rare and historical map collection holds over 8,000 rare original maps plus more than 100 original atlases with maps of significance, including some of the earliest cartographic charts of Australia, the Pacific and other parts of the world. Four maps are highlighted here and they depict Asia Minor—or the modern-day equivalent of Turkey and parts of Armenia, Cyprus, Lebanon, Syria and Bulgaria. They were donated as part of a collection of 130 maps to the University in 1991 by Australian diplomat Ronald Walker and his wife Pamela. Ronald and Pamela Walker made several donations of rare maps over the last 20 years. The first donation was of Asia Minor maps and later donations included more than 70 rare original cartograph items from the 16th and 17th centuries of Constantinople and other parts of the world. Walker was posted to the Turkish capital Ankara in the 1970s where the couple begun their collection of ‘maps of Turkey before 1700AD,’ much of which the University now owns. [1.]

These four maps are all from the 1500s, but are based on 2nd Century AD Greek mathematician, astronomer and cartographer Claudius Ptolemy’s (c.100-c.170 CE) Geographia. Geographia was a complex document: an atlas, geographical treatise and gazetteer, yet there is some debate as to whether the original text contained maps at all. [2.] Regardless, Geographia provided an impressive mathematical system and coordinates for charting world and regional maps, and nearly 8,000 specific place names of the known world. [3.]

Over 1000 years elapsed before Geographia began to be circulated in Europe. It was likely first brought to Florence in Greek by Manuel Chrysoloras (1355-1415) in 1397 and was translated into Latin c. 1409 by Jacobus Angelus (1360-1411). [4.]

The majority of medieval maps in Europe were Mappaemundi, or literally World Maps. [5.] Despite their name these maps were lacking in much detail, but perhaps more importantly, they demonstrated a fundamentally different approach to the purpose and display of geographical knowledge. That is, the charting of places in the near and far-off world was often coupled with a direct allegorical or spiritual interpretation. [6.]

For example, Mappaemundi varieties such as the tripartite or famed Hereford map fairly accurately split the (known) world into three continents: Europe, Asia and Africa. The Holy City of Jerusalem sits at the centre of the map as both the literal and theological centre of the world, and on tripartite maps, each of the continents inherits the genealogy of one of Noah’s three sons after the flood. [7.] What Ptolemy’s Geographia offered the European Renaissance was a system of the world and known geography with replicable mathematical accuracy, significantly divorced from theological implication.

While these maps of Asia Minor are of recognisably the same location, they have small variations. These variations are quite understandable: the mapmakers were interpreting the coordinates and toponyms in the Geographia’s gazetteer, a task which must have required not only sound theoretical understanding, but immense technical skill. [8.] And while they were more geographically accurate than their medieval counterparts, they did embellish on their source here and there: for example the maps by Waldseemüller and Münster here depict little castles at cities, sea monsters and ferocious beasts.

Like so much of the Renaissance, this re-discovery of Classical knowledge brought with it a version of world beyond the confines of Europe and religion, making the world—literally—a bigger place.

Bianca Arthur-Hull

Special Collections blogger

Notes and further reading

[1.] David Jones and Julianne Simpson, Peregrinations in Asia Minor. European Descriptions and Cartography in the 16th and 17th Centuries. University of Melbourne Library, 2005.

[2.] Evelyn Edson, The World Map, 1300-1492: The Persistence of Tradition and Transformation. JHU Press, 2007.

[3.] Niklass Görsch, ‘Ptolemy’s Geography and the Tabulae modernae – A Comparison of Maps Using the Example of the Arabian Peninsula’ Proceedings of 22nd International Conference on Cultural Heritage and New Technologies, Vienna, November 2017. Published February 2019, Wein Museum.

[4.] Evelyn Edson, The World Map, 1300-1492.

[5.] Niklass Görsch, ‘Ptolemy’s Geography and the Tabulae modernae…’

[6.] Evelyn Edson, The World Map, 1300-1492.

[7.] Evelyn Edson, The World Map, 1300-1492.

[8.] Elizabeth Baigent and Renate Burri, ‘The Rediscovery of Ptolemy’s Geography (End of the Thirteenth to End of the Fifteenth Century),’ in Imago Mundi, vol. 61, no. 1, 2009, pp. 124–125.

Leave a Reply