The Fairy Story That Came True: A Tale of Petrol

Heather Berry

The Shell Historical Archive, housed at the University of Melbourne Archives contains a rich variety of photographs, advertisements, and other ephemera which showcase the development of not only a large petroleum corporation, but also the development of Australian roadways and car culture. Perusing the collection, the advertisements in particular spoke to me as representations of the stylised happy cartoon families that we associate with pre- and post-war advertising (See Figure 1) that are so often incorporated into or even nostalgically form the basis of our idea of ‘vintage’, including the John and Betty readers used in Victorian primary schools.

In amongst these romantic depictions of Australian family life, I was drawn toward a fairy story for children, with a delicate watercolour cover of a fairy on the back of a butterfly titled ‘The Fairy Story That Came True’, reference code 2008.0045.00504. This 1923 book was published in Melbourne, and is beautifully illustrated by Ida Rentoul Outhwaite, a notable Australian author of fairy stories. It is now a coveted collectors piece, selling for $3,000 on one antiquarian bookseller’s site. The book appears to be similarly laid out to other children’s fairy stories, and while children’s books often contain moral stories and instructions on how to behave in contemporary society, few contain such capitalist instruction.

The story is about a group of fairies called Shell fairies (so called as they live in shells), who are famous for how quickly they can move about. They possess the Essence of Speed, found in a cave, which is described as a liquid ‘white, like water, pure, and had a sweet, pleasant odour’ (p. 11).

The fairies become trapped in the cave, but are advised by a disembodied voice that they must work to increase the amount of Essence of Speed, for it will be ‘sought by the greatest empire the world will know’ (p. 14) and thus it was discovered – and here the tone changes somewhat, becoming decidedly more pragmatic – by a man with a drill.

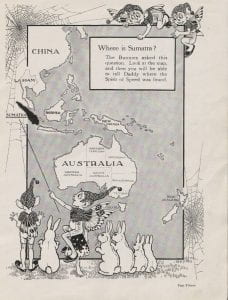

This page (See Figure 3) is accompanied by a map illustration, educating children about the whereabouts of Sumatra (the alleged setting of the story, though this is its first mention), advising them that with this newfound geographical knowledge they will be able to ‘tell Daddy where the Spirit of Speed was found’ (p. 15).

This Spirit of Speed is reported by the book to be ‘just as pure, and have just as pleasant and sweet an odor as when the Fairies used them’ (p. 16). The book ends on the exhortation for children to ‘tell daddy he can use these same pure drops of the Spirit of Speed’ (p. 16) (See Figure 4).

Today the Australian Code for Advertising and Marketing Communications to Children does not allow for advertisements to directly address children nor to instruct them to ask their parents to purchase items (Australian Association of National Advertisers, 2017), so it is amusing, and somewhat jarring, to see the tactic being use so blatantly in older advertisements.

If this book was widely distributed, it likely would have been an effective method of advertising: Lindquist’s 1979 study concerning the effects of advertising on children found that when advertisements were in print form, such as National Geographic or Boy Scout magazines, children felt much less negatively about the advertisement. A feeling of legitimacy – books and magazines are often gifted to children by adults – perhaps provides an implied endorsement, and ‘these young people could also be feeling that there is sanctity in the printed word’ (Lindquist 1979, p. 411). Especially so in the case of this book – illustrated as it was by one of the foremost children’s fairy story illustrators of the time. The only clue I was able to find about Rentoul-Outhwaite’s link to Shell was that she was born in Melbourne, where much of Shell’s warehouses and refining plants were (Shell 2021), perhaps she had made some connection? Looking at her prolific output throughout the 1920s, it seems as though she was not wanting for work. She held many exhibitions of her illustrations, and her books were sometimes published as lavish collectors’ editions (Pryor 2018). While research did not shed any light onto why she specifically teamed up with Shell, I did discover some examples of wartime illustrations from her hand, showing that her work was not always pure whimsy.

Pandering to children in order to secure family purchase of their petrol is also seen in other Shell advertisements, such as the ‘Shell Passports’ advertised in Figure 1. Indeed, as I was describing this book to my partner, he recounted an anecdote about his childhood; due to a promotion aimed at children running at 7-Eleven, he and his sister ensured that their parents were only able to purchase petrol at 7-Eleven for a considerable period. Interestingly, he doesn’t even remember what the incentive was, but he does remember the petrol station. Anecdotal though it may be, such a memory provides an interesting commentary on brand recognition and advertising to children, when taken in conjunction with the Lindquist study referenced above, it is likely that ‘The Fairy Story That Came True’ was a successful way for Shell to advertise to children, and therefore the family unit.

If nothing else, it’s a beautiful little story that leans toward absurdity in its ending in a way uncommon to children’s fairy stories – with a petrol advertisement.

References:

Australian Association of National Advertisers, 2017, Code for Advertising and Marketing Communications to Children, accessed at <https://aana.com.au/content/uploads/2014/05/AANA-Code-For-Marketing-Advertising-Communications-To-Children.pdf>

Lindquist, J.D., 1979. Children’s attitudes toward advertising on television and radio and in children’s magazines and comic books. ACR North American Advances, no. 6, pp. 407-412.

Pryor, C 2018, ‘Fairy-tales, feminism and fame: The story of Ida Rentoul Outhwaite’, ABC Radio National, 1 October 2018.

Shell 2021, Shell celebrates 120 years in Australia, viewed 21 September 2021, <https://www.shell.com.au/about-us/120years-in-australia.html>

The Fairy Story That Came True 1923, Anderson Gowan Pty Ltd, Melbourne.

Leave a Reply