A life in 22 boxes

Jane Beattie, Assistant Archivist – University of Melbourne Archives

Sophie Garrett, Assistant Archivist – University of Melbourne Archives

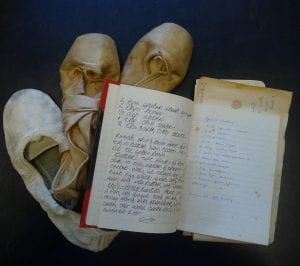

Two pairs of ballet slippers used by Juan Cespedes are preserved in the John Harvey Foster collection, along with research material and personal effects such as Foster’s diaries and a notebook of recipes written by the pair.

These items highlight the enduring nature of not only records but of people. The hopes and dreams of the future, courtship, family feuds, deaths and births of dynastic families alongside struggling migrant pioneers are played out in thousands of pieces of correspondence. The business ventures and failures, take-overs and expansions of family run stores and colonial interest shown in leather bound volumes of business records. Sketches by an Indigenous father attempting to support and keep his family together. Community, union and political groups laid bare through correspondence and minute books detailing complex relationships with the public and governments of the day. Visitors are constantly surprised by the vibrancy of records housed in stark, cold order.

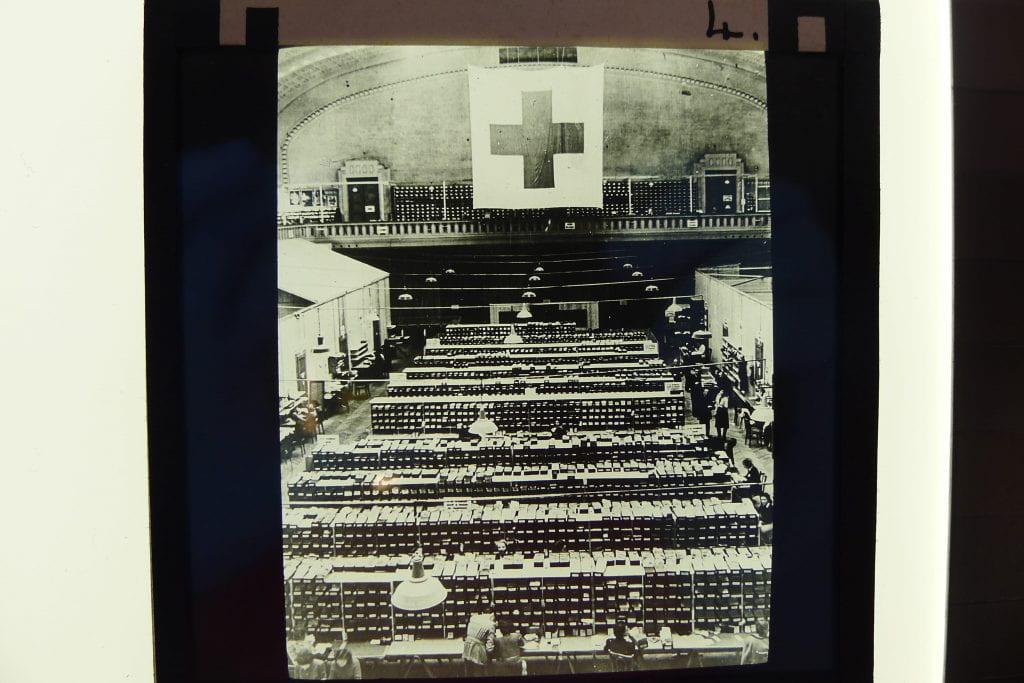

The collection of John Harvey Foster, is housed in 22 plain brown boxes that give no clues to the emotional depth of their contents. Letters, photographs and ephemera reveal the relationship between Foster and his partner, Cuban dancer Juan Cespedes, whose ballet shoes are an unexpected treasure in a repository filled mostly with paper. Foster was a lecturer in History at the University of Melbourne from 1970 until illness forced early retirement in 1993; he died the following year. Scholars who share an interest in German Jews will be interested in the research notes and oral histories contained in these boxes while others will be intrigued by Foster himself, or the heady decade of the 1980s.

Foster’s literary scope covers the research publications of ‘Community of Fate: Memoirs of German Jews in Melbourne’ and ‘Victorian Picturesque: The Colonial Gardens of William Sangster’. The manuscript for Foster’s memoir ‘Take me to Paris, Johnny’ complete with editor’s comments also forms part of this collection and complements other UMA collections that provide insight into the publishing industry. Encompassing the racial and sexual prejudices of Australian and US culture in the mid to late decades of the twentieth century, ‘Take me to Paris, Johnny’ tells of the life and death of Cespedes, who he met in New York in 1981.

In almost every collection at UMA is a story that grounds us in the larger picture of what it means to be human. Then there are the smaller, quieter stories that can be found in the simple act of ensuring two pairs of used ballet slippers are kept in permanence.