Lab-reared mosquitoes maintain their lust for blood

Words and images: Perran Ross

Modified mosquitoes raised in laboratories are being released into the wild in disease control programs. These mosquitoes will still bite you, but they’re less capable of transmitting the viruses that cause dengue fever, Zika and more. This antiviral effect is caused by infection with a bacterium called Wolbachia, which occurs naturally in most insect species. This bacterium has been transferred to the dengue vector mosquito Aedes aegypti, where it interferes with viral replication and can spread through populations. Soon, genetically modified mosquitoes will be released in similar programs, targeting other mosquito species and pathogens like Plasmodium, which causes malaria.

For these programs to succeed, the mosquitoes being released need to be able to survive and reproduce in the wild. Previous research from our group shows that mosquitoes can adapt to laboratory conditions and suffer from inbreeding, likely reducing their performance in the wild. A critical component of mass rearing is the source of blood provided to mosquitoes, which the females need to lay eggs. For Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, human blood is best. In nature, this species feeds almost exclusively on humans, and using non-human blood reduces their reproductive capacity, especially when mosquitoes are infected with Wolbachia.

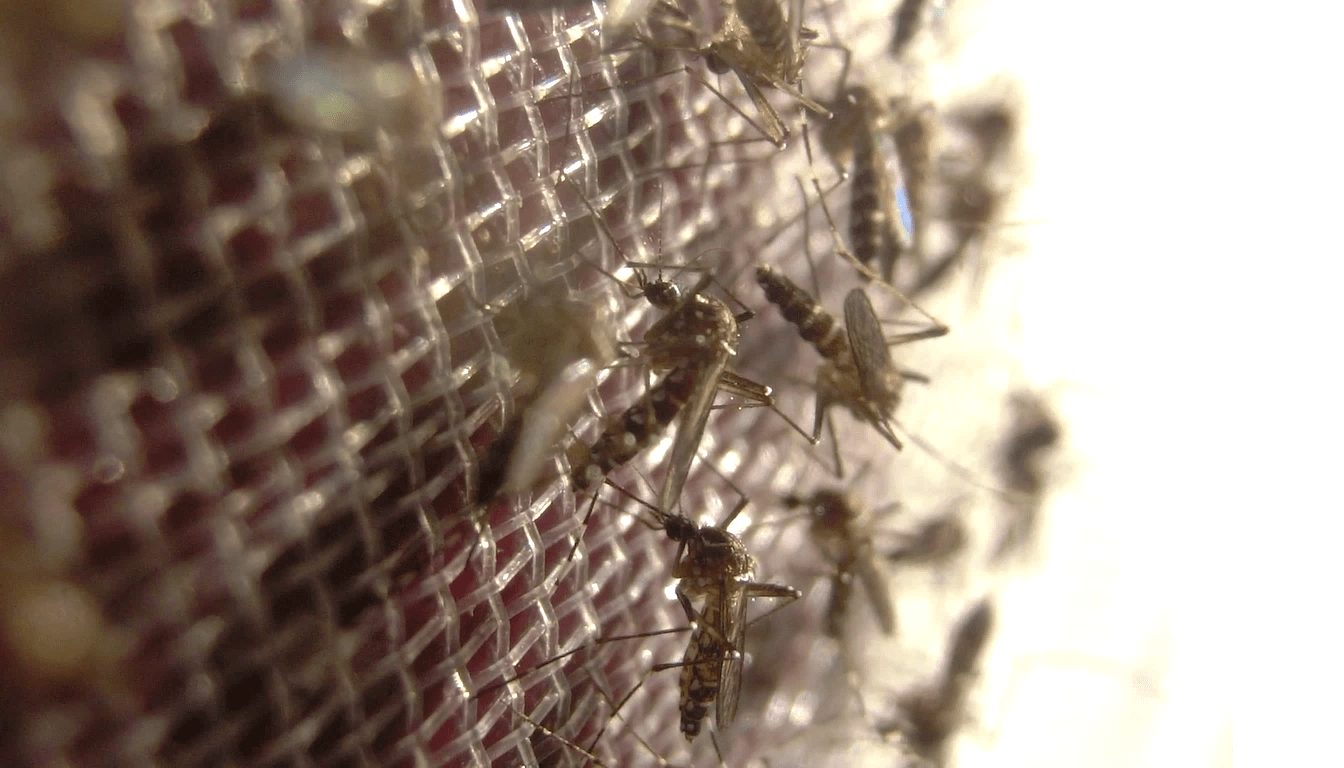

Aedes aegypti mosquitoes prefer human blood, but in the laboratory they’ll take what they can get. Source: Getty Images

When raising mosquitoes in the laboratory, human blood can be provided in two main ways. The first way is simple: roll up your sleeve, insert your arm into a cage of mosquitoes and resist the urge to swat them. Within seconds they will descend upon you for the feast of their lives. But in many situations using a human volunteer isn’t feasible. In areas where dengue is endemic, people risk transmitting dengue to others via the laboratory mosquitoes. When rearing mosquitoes on a mass scale it can be time consuming and costly to use human volunteers. When I maintain mosquito colonies in the laboratory, I can feed a few thousand over the course of a few hours. If I keep going, I will eventually wither away; it only takes about a million mosquitoes to drain a human of blood completely.

Increasingly, blood is provided to mosquitoes artificially through membrane feeding devices as an alternative to human volunteers. But to a mosquito, there’s nothing like the real deal. Female Aedes aegypti use a variety of cues to locate and feed on a host, including breath, skin odors, heat, and moisture. Their proboscis is adapted to pierce skin and locate blood vessels. Membrane feeders lack many of these qualities, and for this reason mosquitoes may lose their ability to seek and feed on human hosts if they’re fed on membranes for too long.

We tested this hypothesis in a new study by keeping Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in the laboratory for a year on different blood sources: human arms and membrane feeding devices. We then tested their ability to locate and feed on humans. In laboratory experiments, the two groups did not differ in their attraction to humans or individual cues like heat and odour. Membrane-selected mosquitoes were also just as capable of feeding on humans, with similar feeding times and blood meal weights.

But when we tested host-seeking under more realistic conditions in a semi-field cage, the membrane-selected mosquitoes were slower to locate the human bait. Going back to the laboratory, we found that several traits like larval development were impaired in the membrane-selected mosquitoes. Female mosquitoes didn’t feed very well on the membranes (see below), reducing the number that contributed to the next generation. This leads to inbreeding, which might explain the effects seen in some experiments. Although our membrane material didn’t work well, the use of alternative materials may avoid this issue entirely.

Female mosquitoes struggling to feed on blood provided via a membrane.

Our study shows that using membrane feeders probably won’t lead to an inferior mosquito. Membrane feeders can be used to raise mosquitoes on a mass scale as an effective alternative to human volunteers if population sizes are kept high. And it seems that once you have a taste for human blood, there may be no going back!