Uncovering Connections in Britain’s Empire: An Interview with Professor Zoë Laidlaw

Upon finishing her Honours at Melbourne, Zoë Laidlaw went on to complete her postgraduate degree at Oxford. After 20 years in the United Kingdom, she returned to the University of Melbourne in September 2018. PhD candidate Jonathan Peter spoke to Zoë recently about her experiences as an academic, her research interests, as well as current and future projects.

You finished your undergraduate degree in Melbourne and completed your PhD in the UK before eventually coming back here. Could you tell us a little bit about that journey and the choices you made along the way?

I completed my Honours in History here in 1996. I had a bit of an unusual track record, because you could then take two degrees at once. I did Arts and Science, and my first Honours was actually in Maths. However, after completing my History Honours thesis with David Philips, who was beginning work on how the British treated Indigenous people across the empire of the 1830s, I knew I wanted to be a historian. It was a fantastic experience. Melbourne’s Honours program was, and still is, really vibrant. It inspired me to pursue the history of colonialism at graduate level.

I was fortunate to secure funding for my doctoral studies in Oxford. I thought that the UK would be a good place to study Britain’s imperial history, not only because of the archives there, but also because of the chance to work with people interested in both other parts of the Empire and Britain. It was a chance to see Australia’s history from a different perspective.

It was a really exciting time in Australian History. When I started my undergraduate degree in 1991, the Mabo case was ongoing and its reverberations were considerable in historical studies as well as political life. It helped non-Indigenous Australians start to recognise how important Indigenous History was, and how problematic existing interpretations of Australia’s colonial history were. I hadn’t learned Indigenous History at school; work by scholars like Henry Reynolds, which I encountered in my first year, was very fresh and important. It inspired my interest in studying History further. But, by the time I was completing Honours, I thought it would be good to put those new understandings of Australia’s past within the wider context of colonial settlement across Britain’s Empire.

Oxford helped me in doing this, because there were a lot of people working on similar questions. It had a very large, dynamic, well supported and cosmopolitan graduate cohort. There, I met many people who were highly expert on the history of other parts of the former Empire.

I had always intended to come back to Melbourne, but I got a job at the University of Sheffield. They started a program in International History in 2001 and made three appointments, including me. I worked there for four years, mostly teaching the history of Britain’s empire.

In 2005 I moved to Royal Holloway, which is one of the colleges of the University of London. The colleges are individual institutions, but also part of a loose federation, which fosters collaborative research and teaching. The University also houses the Institute of Historical Research, a home for all historians in the UK. Working in London was a brilliant experience. I was exposed to a lot of different opportunities, especially with cultural institutions like the British Museum and the British Library and professional bodies like the Royal Historical Society, and I think this expanded the types of history I was interested in. I worked at Royal Holloway until September 2018.

The opportunity to come back to Melbourne was one that I couldn’t turn down. It was a fantastic chance to come back and to see what’s changed in Australia. It was an intellectual choice as well. Having spent twenty years in England seeking a broader perspective on colonialism, it seemed important to come back and see what settler colonialism looked like from an Australian perspective.

Your study of imperial and colonial history has taken you across different parts of the former British Empire, covering numerous historical figures from different backgrounds as you examined the importance of networks between the colony and the metropole in establishing colonial governance. Why did you choose this approach to studying history, and why do you think it is important to understand today?

Networks of connection are central to all of my past work, the work I’m doing now and what’s going to happen next. That interest arose from my dissatisfaction with the way imperial history was being written in the 1990s, which was still quite top-down. I wanted to understand how power was conveyed, negotiated and sometimes subverted, over vast imperial spaces. Even today, to get someone at a distance to do your will is difficult, and it was even more so in the early to mid-nineteenth century. I wanted to know more about how those difficulties were negotiated in Britain’s empire.

But when I arrived in Oxford, like lots of PhD students, I had written a research proposal that was quite different! It was during my first year, while I was reading archival materials, that I became interested in the way power was accrued and disseminated in different parts of the Empire. I started looking at the Colonial Office records at the National Archives in Kew, and realised that they were full of interpersonal communication and personal concerns. Much of the correspondence that I was looking at (dating from about 1815 to 1840) was about trying to find a position for a younger family member, or to extract some kind of favour from the imperial authorities, or to make an impassioned case for something that the government had little interest in.

These records showed me that these archives, far from being dull or bureaucratic, were gritty, interesting and contested. I realised that a great diversity of opinions and people were represented in the official record. Many of them had made some impact on the historical record, but few had been the subject of historical scholarship, because ‘history’ had tended to revolve around governors and other people who accrued power.

But it was clear that there were other voices and experiences represented within the archives. Major historiographical shifts were going on at the time, such as the emergence of New Imperial History in the 1990s, which focused on the impact the Empire had on metropolitan society. Scholars like Ann Laura Stoler and Frederick Cooper insisted that we place “colony and metropole in one analytic field”. Viewing those intellectual debates through the official archive, what stood out for me was how power was articulated, and how information was disseminated, and how that changed from being very personal (and nepotistic) to more impersonal and bureaucratic in the 1830s.

This matters because it has allowed us to tell different and sometimes more subversive stories about Britain’s empire and its constituent parts. We’ve been able to foreground better the experience of people who have been written out of history, or just overlooked, but also to understand how the great bureaucratic machinery of empire worked.

For example, one of my first publications was about Anna Gurney, an unmarried cousin of Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton, who chaired a British Select Committee on Aborigines between 1835 and 1837. Buxton’s leadership of that committee was dependent on Anna Gurney; his daughter, Priscilla; his sister, Sarah Maria; and his wife, Hannah. Collectively, they collated, edited and repackaged evidence from around the empire. Anna Gurney was in large part responsible for the committee’s report, which became a document that reverberated down the nineteenth century.

The body of work covering women, Indigenous peoples and slaves, and foregrounding their stories, is constantly increasing. While not always easily accessible, their histories are recoverable, and it is important to present them. I hope to get away from the swashbuckling ‘Heroes of Empire’ who dominated past versions of imperial history. We know that there were always women there, people carrying the bags, guiding ‘explorers’ and the like, and that their decisions and experiences played just as important a part in co-constituting the empire. The study of these relationships, their movements, the pinpointing of who knew who, how they corresponded and what they thought was important, has proved to be one way of uncovering some of this history.

When looking at these networks of colonial governors, humanitarians and everything in between, is there one figure that you think stands out from the rest?

One figure I admire is an Ojibwe woman from around the Great Lakes [of North America] who went by two names. Her preferred name was Nahnebahwequa, but she was also called Catherine Sutton. She lived from the 1820s until 1865. Both her parents were Indigenous, and she grew up with her uncle, another remarkable figure who called himself Peter Jones, but was also known as Kahkewāquonāby. He was one of the first Indigenous Methodist ministers around the Great Lakes.

Nahnebahwequa travelled back and forth between Britain and Canada during the course of her life. She was very eloquent, and made representations on behalf of her people to audiences of thousands in the UK in spite of her many health problems. She met Queen Victoria and senior politicians, to make her case for the land rights of her people.

In the eyes of the colonial state, Nahnebahwequa suffered the double disability of being Indigenous and a woman. In her life you can see the contortions resorted to by the colonial authorities in order to dispossess Indigenous people. This was a period of British American history where land was being ripped away from the Indigenous people of Canada at a horrifying speed. Millions of acres were lost over a few decades. By the end of her life there was very little land left in Indigenous hands; it had all been transferred to settlers. Nahnebahwequa became ineligible for one type of title (as an ‘educated’ Indigenous person), because she was a woman and she married a non-Indigenous man. And yet, after marrying a white man, she was still disadvantaged as an Indigenous woman. She spoke with great clarity about her situation, and that of her people, and that echoes across time.

Could you tell us a bit about the research you’re working on right now, and perhaps any interesting things you’ve uncovered so far?

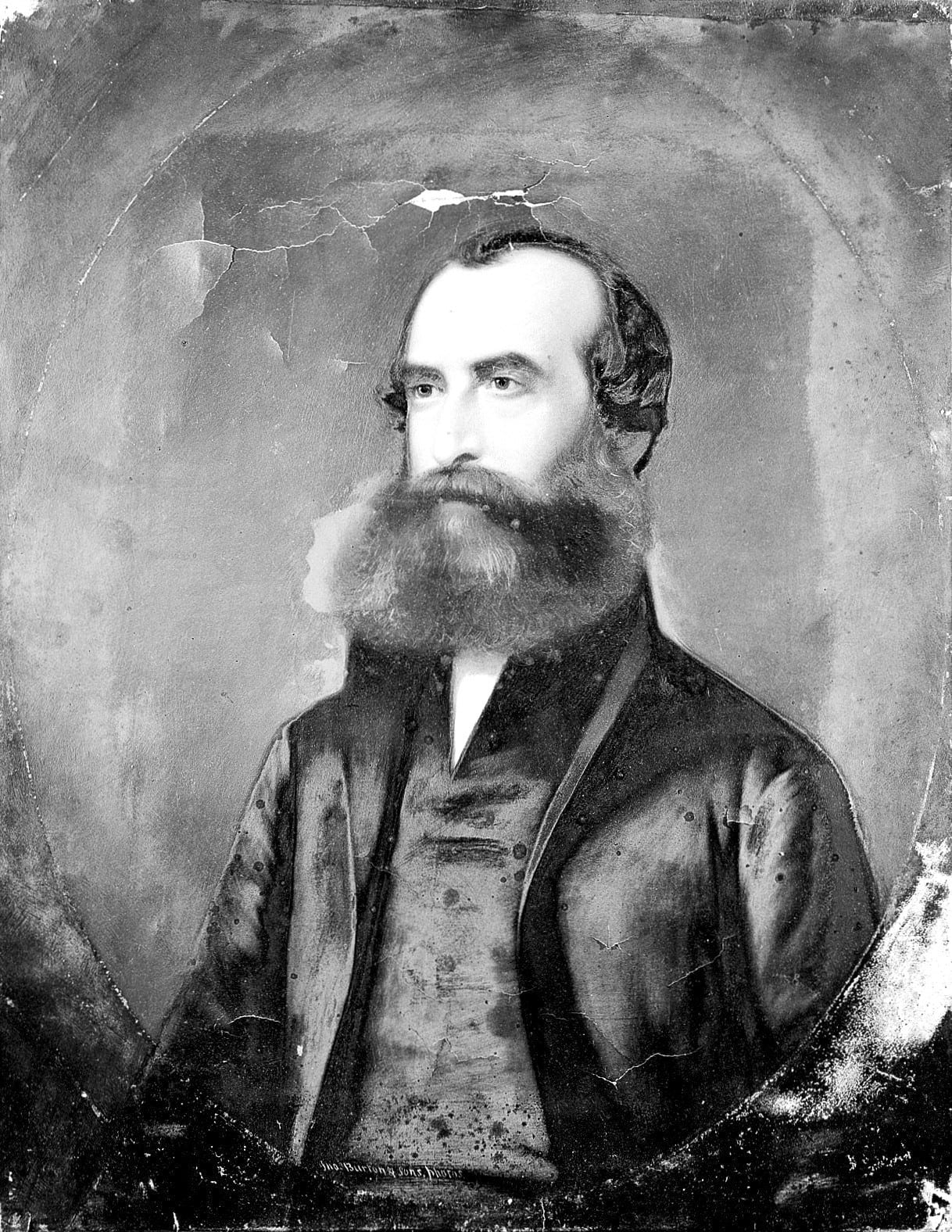

I’m currently writing a book about the life of Thomas Hodgkin, who was born in 1798 and died in Palestine in 1866. He was a Quaker who grew up and spent most of his career in London. He studied in Edinburgh and Paris with some of the great medical doctors and scientists of the early 1820s.

He has a string of achievements, such as publishing one of the first papers about the microscopic properties of the cell and writing a study of Morocco’s geology. But he was driven by his social conscience, shaped by his Quaker upbringing. In the 1830s, as the campaign for slave emancipation came to fruition, Hodgkin transferred his attention to the plight of Indigenous people across the world but particularly in the British Empire. He would also become Britain’s first Consul for Liberia, the colonial state established by free African Americans. Liberia’s colonial history was very problematic: many of the white Americans who supported it were eager for African Americans, slave or free, to leave the United States – they intended a whitewash.

Hodgkin thought differently. He saw Liberia as an opportunity for African Americans to lead lives of liberation in which they demonstrated conclusively their equality with White people. Through his numerous connections around the world, such as his network of Quakers and other activists, he was convinced of the biological unity of humankind. To him, any difference in the achievements of different societies was due to environment or oppression, as opposed to any inherent incapacity. He wanted to found other new colonies around the West African coast for former slaves and free people of colour from the British Caribbean. There were obviously many problems with this, but Hodgkin did not recognise them. He was both young and very naïve. Instead of advocating immediate slave emancipation, for example, he thought a gradualist approach was best – where slaves would be ‘elevated’ to freedom by working, literally, to buy themselves: he didn’t recognise this as either paternalistic or offensive.

Hodgkin also appeared before the Select Committee on Aborigines we talked about earlier, giving evidence even though he’d never been to any of the colonies. He presented a utopian view of how colonisation could be made to work better. He focused on achieving a harmonisation between Indigenous societies and an idealised version of British civilisation. This was naïve: he knew that Indigenous people across the world – in Australia, Southern Africa and the United States – were being dispossessed, persecuted and murdered by an onslaught of European settler colonialism. But he believed a utopian form of colonialism was possible and, pragmatically, better than allowing existing forms of colonialism to run their course. He thought the mechanisms for change were information and education: if Britons knew all the facts they would change their behaviour and the structures of colonialism; if Indigenous peoples were well educated they would be able to defend their rights.

Though his optimism eventually transitioned into depression, Hodgkin clung on to a utopian view that colonialism could be a mechanism not just for transforming Indigenous people, but also for civilising Europeans. European society had, through slave-owning and colonialism, become toxic. Hodgkin and those he was connected with saw a very different form of colonial activity as a means to rejuvenate and improve not just colonised subjects, but also Europeans.

Hodgkin’s personal archive (at the Wellcome Library in London) is amazing. He founded the Aborigines’ Protection Society [APS] in 1837, and it holds many hundreds of letters to and from people all over the world: missionaries, Indigenous leaders, politicians, colonial officials, scientists, farmers and merchants. They cover the situations humanitarian activists and Indigenous people faced in Britain’s colonies, South America, the United States and across the Pacific.

Quakers like Hodgkin were skeptical about missionary activity as they didn’t approve of evangelisation. He was also critical of government schemes to protect Indigenous interests, like the Protectors of Aborigines in Australia. He thought they were either ineffectual or in thrall to settler interests. Thus, he put the APS at odds with its most obvious communities of supporters, and it was vilified by settlers and colonial speculators as out-of-touch and interfering. Although the society endured until 1909, during Hodgkin’s lifetime it had limited success.

Despite this, Hodgkin’s archive contains an amazing wealth of communication from figures like Nahenbahwequa, Peter Jones, pre-eminent missionaries, colonial governors, politicians, scientists and people collecting ethnographic data from around the world. For me, his life and archive provide an intriguing window onto how power and ideas were disseminated at the time.

We’ve tended to see humanitarians as working as a bloc, distinct from their scientific counterparts, or people with mercantile concerns, and we’ve also tended to study regions of empire in isolation from one another. In fact, Hodgkin’s life, and the lives of people like him, show a far messier situation, in which some individuals were highly interconnected. I think his life history can shed light on bigger questions about how we think about empire, and how we think about relationships between different parts of it.

You completed your PhD in 2001. How do you think the landscape of academia has changed since then? What advice would you give to postgraduates looking to embark on an academic career today, especially compared to when you first started?

It’s less than twenty years since I was a graduate student, but the landscape is totally different. There were fewer PhD students, and universities relied less on a casual workforce. Early career researchers faced a shorter period of uncertainty. I think it’s always been tough to be a PhD student, but twenty years ago the chance of getting security earlier on was greater. The pressure for PhD students today to develop to a rich CV in order to ensure funding and positions to get you through that long period of short-term contracts, is very tough. It’s difficult to mitigate.

In comparison to the many skills expected of PhDs today, we had comparatively scant CVs and publication records. Today it’s very much a balancing act. The first priority has to be to produce an excellent dissertation that will meet the requirements and make an original contribution to the existing body of knowledge. And a PhD also should equip students with the knowledge to research, teach and intervene in debates that can only be understood fully if we understand the past. We need History PhDs for these things.

But today’s PhD students also need to demonstrate flexibility in building connections not only with fellow historians, but also with museums, education, other community groups, to make sure that their work has an impact. We take our engagement with the wider world much more seriously than when I was a student, which is great. And we see historians intervening across a range of media and in newly creative ways. But this, and the pressure to publish, is very absorbing of time and energy, and takes up much more emotional and intellectual space.

I think a PhD has to be a project that you are highly committed to. I also think that being strategic about your topic, the skills you want to show off in your thesis and the bits that you publish, are all very important. I’ve been involved with the SHAPS Research Training Committee this year, and I am constantly impressed by our students and their ability to balance what is expected of PhD students today.

When I think of what got me through my PhD and the subsequent years, the personal and intellectual friendships I made along the way were critical. When I look now at whose work I’m citing, I realise that I’m still in dialogue with people I met when I was a graduate student. Lively debates at conferences are important, of course, but as a PhD student you are obliged to read deeply, carefully and widely, and you have the chance to debate ideas with your peers over time. Always be kind to your colleagues! The friendships you make as a student really nurture you over the years.

How would you describe your experience since returning to Melbourne so far, and what are your plans for the future?

It’s been fantastic but also, in some ways, disconcerting. It is odd to return to an institution where I was a student, especially after a twenty-year gap. The university and the city are still recognisable, but also transformed, much larger, more diverse and more internationally focused. It’s terrific to be in SHAPS, and I think that it’s a very dynamic environment. It’s rewarding to be involved in new conversations here, especially where the starting point is different from when I was in the UK. Becoming involved with some of our Honours and graduate students through supervision over the last year has also been really rewarding.

I’m also very excited that the school has appointed a historian of Indigenous History – Dr Julia Hurst – who will be starting next year. I’m enjoying being part of the Indigenous Settler Relations Collaboration based in the School of Social and Political Sciences. I was previously a partner on the ARC Linkage project Minutes of Evidence with colleagues in SSPS, and the wealth of experience across the wider university is brilliant. It’s also brilliant to be in the same timezone!

I’m finishing the book about Thomas Hodgkin and I’ve also got other interesting projects. One ARC Discovery Project on which I’m an investigator, Inquiring into Empire, is examining the imperial inquiries that the British government sent out to between 1815 and 1845. Imperial commissions of inquiry went to Sri Lanka, Australia, South Africa, Mauritius and the West Indies, among other parts of the British Empire. Part of that project involves digitising the archival records of those commissions, and analysing both how Britain came to terms with Empire, but also how the Empire spoke back to Britain. For example, in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon), more than 700 petitions were submitted to a commission of inquiry by very ordinary people looking to be heard by the imperial authorities. It’s a fascinating project. My other ARC project, which will get underway in 2020, Western Australian Legacies of British Slavery, explores the ongoing impact of wealth derived from British slavery in shaping colonial immigration, investment and law.

Zoë Laidlaw will be teaching undergraduate subjects from 2021, including co-teaching HIST30068 History of Violence with Dr Jenny Spinks, and a new second-year subject, Britain’s Empire: Power and Resistance.

Feature image: British Empire Throughout the World, Exhibited in One View. John Bartholomew via Wikimedia Commons