Under No Management, Since 1976: A History of the University of Melbourne Food Co-op

For her final-year capstone project, History major Claire Hannon decided to investigate the origins of a longstanding student institution: the University of Melbourne Food Co-op, established in 1976. What had driven the Food Co-op’s founders? And how might the history of the Food Co-op help to inspire new forms of student activism today? Claire’s project took her into the history of campus life and food politics and led her to reflect on the differences in student relationships to the University then and now.

History capstone students are encouraged to experiment with finding creative and engaging ways to write history. Claire succeeded outstandingly well in bringing this history to life, in a project based on oral history interviews with two of the co-op’s founders and research drawing on the Farrago archive. She tells a rich local story animated by intellectual curiosity and the drive to gain a deeper historical perspective on the urgent questions facing us today. We publish her essay below as an example of the superb work produced by our top final-year History majors.

Inside a room on the first floor of Union House at the University of Melbourne, there is a sign which reads: ‘The Food Co-op; since 1976. Under no management’.

The University of Melbourne Food Co-op is nearly 44 years old. On the Co-op’s website, which was last updated about five years ago, there is a page entitled ‘A Brief History of the Food Co-operative’. However, the essence of this page can be summarised by the following excerpt: “due to the nature of the business, our history is somewhat skint; the who and how it all began seems to be lost into the steam of the boiling chickpeas”.

Despite the hard work and dedication of the current volunteers, the Food Co-op isn’t exactly flourishing. Few students today are aware that the Co-op exists, and even fewer are willing to volunteer. The Co-op operates at reduced hours, getting an average of twenty customers per day. I found myself wondering whether it had always been this way.

I delved into the archives of Farrago – the University of Melbourne’s student publication – to find out more about the Co-op, and came across the name of the woman who first proposed the venture: Alison Caddick. Alison was kind enough to let me interview her, and encouraged me to interview her friend and collaborator, who took over her position at the Co-op after she left: John Wiseman. So, with the information provided to me from the pages of Farrago, and from my conversations with Alison and John, I set out to uncover the history once thought lost to the steam of boiling chickpeas.

What is a Co-operative?

So, to begin: what actually is a co-op? Co-op is short for co-operative, which, put simply, is an organisation in which a group of people work together, bound by certain principles, to meet a shared goal. The philosophy that guides co-operative enterprises is that of the Rochdale Principles, which were formalised in England in the mid-nineteenth century, and have been adapted over time. The enduring principles are:

- Membership is to be open and voluntary.

- There must be democratic member control.

- Members make economic contributions to the co-operative.

- Co-operatives are not-for-profit organisations; any surplus must either be used to help the co-operative, used to aid external activities approved by co-operative members, or distributed amongst members in accordance with their involvement in the co-operative.

- The co-operative must be educational, informing their members and the public about the benefits of co-operative enterprises.

It didn’t take long for the Rochdale co-operative model to spread to Australia; consumer co-operatives were registered in Brisbane in 1859 and Adelaide in 1868. Co-ops can come in many forms – many of the earliest were farmer co-operatives, formed by working men who wanted more control over the distribution of their products. There are also organisations that have flourished in Australia which operate similarly to co-operatives, such as trade unions and credit unions. The Food Co-op is a consumer co-operative; the popularity of this type of co-op peaked in the interwar period before declining throughout the rest of the twentieth century. By the 1970s, Australia’s formal co-operative movement was reaching its end. However, the fertile political climate of the period, which spawned movements such as Women’s Liberation, Gay Liberation and the Aboriginal Rights Movement, brought a burst of interest in co-operatives. Many of the activists were influenced by nineteenth-century Utopian socialism, and wanted to establish co-operatives as alternatives to mainstream society. This is where the Food Co-op comes in.

The University of Melbourne Food Co-op

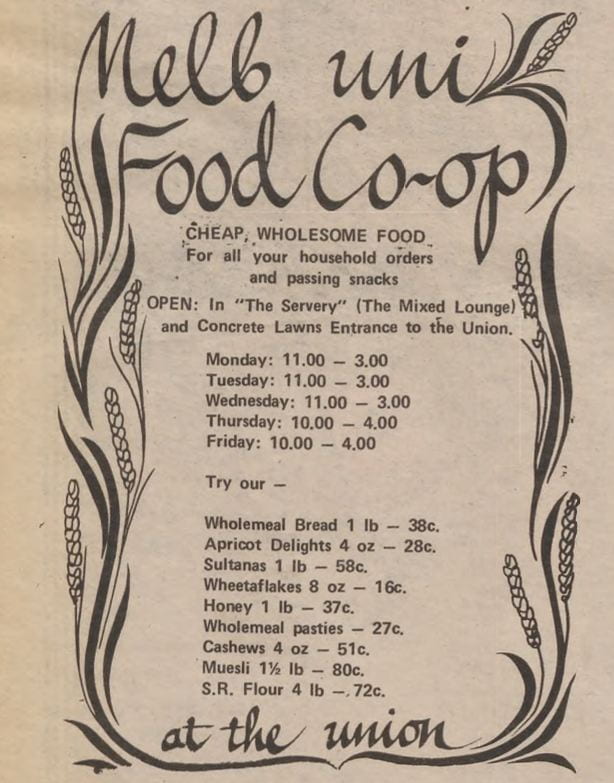

It was in September 1975 that the Student Representative Council’s Welfare Officer, Alison Caddick (who was studying for a degree in Social Work at the time), announced that she planned to establish a food co-operative. It was to operate by buying bulk food at wholesale prices, and then selling it cheaply to students. The Co-op would sell ready-to-eat snacks, but it would focus primarily on encouraging students to become members, volunteering when possible and buying bulk food for their households.

A Food Co-op committee, which included Alison’s fellow Social Work student, John Wiseman, was soon formed, but the University administration rejected their request for the Co-op to be allocated space on campus. To overcome this setback, the committee decided to test the popularity of the Co-op by opening it as a temporary stall during O Week of 1976. Demand was high, and the Co-op quickly became a series of tables in the foyer of Union House, as well as occupying a small tea servery on the first floor, near where the Student Lounge and the Food Co-op stand today.

In July 1976, after extensive discussion, the Co-op committee decided on the following policies:

- The Melbourne University Food Co-op will sell only nutritional and minimally processed foods.

- It will sell goods with a minimum of packaging and will encourage the recycling of containers.

- It will be a non-profit organisation, aiming to cover costs only.

- It will perform an educational role through the type of food it sells, its style of operation, and specific educational programs.

The Co-op was committed to environmentalism, anti-corporatism and community building, and educating people about food. It provided a way, in the words of one of its members, for students to ‘regain some responsibility over [their] own lives’. Members published articles in Farrago about topics like the potential of communal activities to challenge consumer capitalism; eating as a social issue that extends far beyond mealtime; the environmental havoc wreaked by excessive packaging; and the need to reject the norm of highly processed food. Some of these points are so prevalent in today’s discourse, particularly those pertaining to food and the environment, that it’s easy to forget how startling a challenge they were to the status quo of the 1970s.

The Co-op quickly became very successful. By July, there were 35 people volunteering and 85 people on the mailing list. On some days the Co-op took up to $400, which equates to $2,500 in 2019, and the gross total averaged out to $5000 a month – $31,000 today. The meagre space the Co-op had been allocated in the foyer and the tea servery was already proving insufficient to cope with the demand.

Although for the most part the Co-op was flourishing, John remembers there were still issues regarding how to transform high ideals into tangible, sustainable organisational practice. He recalls that, in setting out, the Co-op committee had hoped to run an “entirely voluntary co-operative venture”, but soon discovered that “relying completely and utterly on voluntary labour is a bit of a trick”. So, they ended up hiring a paid manager who had more experience with food. This manager was Dot Ward, the mother of one of Alison’s friends. Although Alison remembers Ward as someone very passionate about food quality and co-operative ideals, John recalls that the employment of a paid manager created ideological tensions by blurring the line between co-operative models and small business models. This tension often arose, and still arises, within radical groups, with the issue being: how can organisations subvert the dominant hierarchical organisational structure, whilst avoiding being dominated by whichever member shouts the loudest?

These issues, though important, did not affect the Co-op’s success. So, to answer my initial question: no, the Co-op was not always struggling in the way it is today. When it first began in 1976, it thrived. This raises the question: why then, and not now? What has changed?

The Context

The Food Co-op couldn’t be started now … or it would be very hard to think of starting it now

—Alison Caddick (2019)

There are two key aspects of the present-day landscape that differ strikingly from the mid-1970s context in which the Food Co-op flourished: the general political climate; and the nature of the University itself.

Across much of the Western world, the 1970s saw the radically oppositional energy of the 1960s develop into a focus on more collaborative, grassroots activity. Famously, the 1960s saw protestors in cities like Prague, Berkeley and Paris defy established ideas about politics and culture. These protestors came from a range of backgrounds and differed in their specific motivations, but in Australia and the United States, they tended to be young, relatively privileged students who wanted to challenge the postwar consumer culture.

As yet, there has not been an extended historical investigation into the Australian experience of that tumultuous period. It seems clear, however, that what set the radical mood in Australia was a combination of the Vietnam War, conscription, and the defeat of the Labor Party and its anti-war platform in the federal election of 1966. These events sparked a series of protest actions including draft resistance, the Vietnam War Moratorium movement, and protests against South African apartheid. Student action at the University of Melbourne peaked around 1971. In May of that year an estimated 1000 students demonstrated their opposition to the University’s admissions regulations by barricading the University administration building so staff were unable to exit. In September, students acted in solidarity with draft resisters sought by the police by occupying Union House for four days, before the police eventually stormed the building.

Many monumental social movements found their voices in the seventies – including Women’s Liberation and Gay Liberation – but the radical activism so characteristic of the earlier period was evolving. In the US, much of the activism seemed to have turned to disillusionment following the election of the Republican Richard Nixon in 1968. However, students and tutors writing in Farrago in the mid-seventies saw Americans starting to transform this feeling into something new. In August 1975, a month before the announcement about opening a food co-op, Farrago ran an article entitled ‘America, Amerika’. It was an interview with Arnold Zable, a former Political Science tutor at the University of Melbourne, who is today known as a celebrated writer and an advocate for disadvantaged communities. Zable was interviewed by Farrago after returning from living as an activist in the US for five years. In the article, he asserts that despite the wave of disillusionment that hit following the decline of the mass anti-war movement, people had been irrevocably changed by the experience. It had started a process of self-questioning, and a questioning of the American identity. He observed that, although the time of thinking in grand terms and expecting immediate results had ended, people were “beginning to come back at the system” by focusing on more practical, community-based movements such as food co-operatives. A change was in the air.

The mood was shifting in Australia too. The seventies brought the election of the Australian Labor Party under Gough Whitlam in 1972, and the subsequent withdrawal of troops from Vietnam. At the University of Melbourne, it brought the campaign to create the University Assembly – an elected body of staff and students that would have a role in decision-making at the University. Alison recalls that rather than necessarily understanding themselves as being in direct opposition to authorities, people were turning their radical energy towards determining whether it was possible to rework relationships of power within structures such as the state so as to make them more collaborative and horizontal. Yet, in Australia too, a sense of disillusionment set in. The Whitlam Government was dismissed, and many students felt that the University Assembly was ineffective, and little more than an example of co-option. In an October 1975 Farrago article, University of Melbourne student Alan Davidson sensed this disaffected mood, but believed that if a political ‘rebirth’ were to come in Australia, it would come as Zable had seen it come in the US; people were going to realise that they could have “power in society over some aspects of their lives through small group actions”. This is the context in which the Food Co-op was born.

During the sixties and seventies, German philosopher Jürgen Habermas wrote essays in which he theorised that a shift in “the grammar of life” was occurring; Alison believes his essays captured the way in which people were striving to create a new culture by putting their lives together in different ways. Although Alison and John struggle to remember many specific details about the Food Co-op, they both vividly recall a range of political influences that fed into the mood of the time. They both cite the Women’s Liberation message, ‘the personal is political’, as a profound influence, for it emphasised the importance of turning a political lens upon practical, everyday activities. This idea is also reflected in the growth of communes and collectives during that period, both at home and abroad. It has been estimated that over the course of the 1960s around half a million people in the United States spent time living in communes. This communal living wave hit Australia, though to a lesser degree, in the 1970s. A notable catalyst was the 1973 Aquarius Arts Festival in Nimbin, New South Wales, after which many people decided to stay on in the area and experiment with alternative lifestyles. It is in this sense that Alison remembers that their political action was never simply aimed at “carving up the social product” in a traditionally partisan way, but at entirely reworking the system.

Marxist alienation theory also had a strong impact on Alison’s circles; this theory claimed that people needed to try to reconnect with the world by learning how to see human subjectivity in the objects which surrounded them, as well as determine how one could build satisfaction into ordinary life through the pursuit of meaning, value and self-expression. Food, as such a basic element of life, naturally became a focus of this type of thinking. John was influenced by Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, which critiqued the ‘banking model’ of change – the expectation that one could simply deposit ideas into people’s heads, and then they would go and start a revolution. Freire argued that instead, transformational change occurs when one meets people where they are already at, by working on practical issues like food, housing, and health.

Although it is not her favourite way of thinking, Alison believes that philosophical theory of the rhizome, as conceived by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, is a useful way of conceptualising the thinking of the time. Something which is rhizomatic grows up from the bottom and spreads outwards; it has no discernible hierarchy, beginning, or ending, and focuses on notions of interconnectedness. It can be connected to ideas about creating and living an alternative culture in order to effect transformational change. In essence, Alison believes they had wanted to build small counter-institutions in which people could develop social connection around a meaningful purpose; the Co-op, she says, was “that kind of beast”.

Another key element of the context surrounding the creation of the Co-op is that the sense of community at the University of Melbourne was stronger in the mid-seventies than it is today. Although the time was not free of divisions – namely between the staff, the students and the administration – and critiques were mounting about the University becoming corporatised and alienating, Alison and John remember that most students invested in the University in a way they no longer do. Although Australian universities were not a paradise for all during this era – the student body was still extremely homogeneous, and power was monopolised by middle- and upper-class white men – it has been characterised by scholars such as Hannah Forsyth as the last days of a ‘golden age’. It was during this period that universities began to shift from being venerated sites of education to becoming deeply wrapped up in questions of economics.

The community that Alison and John remember existing at the University during the mid-seventies can be explained by a number of interrelated factors. A large proportion of their cohort shared communal houses close to campus. This was a part of the mass influx of students into formerly working-class inner-city suburbs that occurred in the 1960s and 1970s. In Melbourne, the primary destination was Carlton, largely due to its proximity to the University. Prior to this period, Carlton had been considered an unsafe and unappealing area, but that perception changed with the arrival of students looking to escape the conservative postwar culture of Melbourne suburbia. The number of both students and academics living in the area grew exponentially between 1955 and 1975, though of course it is important to note that this was also a period when the number of students at the University nearly doubled to 16,000. According to Graham Little’s study of students and the University, published in 1975, students preferred share-houses to flats or residential colleges, and they aspired to form communities within their shared homes. The proximity to campus meant that for many students even home life was centred around the University. More people physically spent time on campus – this was a time when fewer students had jobs, and when lectures weren’t recorded. Further, food itself played more of a role in the culture of the University. Both Alison and John recall the importance of lunchtime in Union House, during the 1.00pm to 2.15pm lecture break, when people would spend time eating together and forging bonds. In addition, it was common for people to cook and eat together in their share houses, so it made more sense to buy food in bulk at the University. The act of buying food for your house at your university also relates in Alison’s mind to the notion of universities connecting into student households in a rhizomatic way, fostering a connection founded on a non-hierarchical relationship.

At the base of all of this is the fact that Alison and John remember the University feeling less like a business, and more like a welcoming community – even a home away from home. Alison recounted an anecdote which is seemingly minor, yet I believe speaks to this point: today, there are technologies placed around the entrances to the University to keep cars out, but she remembers being able to casually drive up and park outside Union House, unload her car and go about her business, much like one would do at their own home. Times have surely changed, and the University has changed with them.

***

By 2026, the Food Co-op will have been around for half a century. It is a living, breathing piece of University history. This essay is not intended to romanticise the era in which it began – the seventies offered visions of utopia to only a privileged few – but is simply trying to understand the state of the Co-op today by turning a lens upon its past. The Co-op thrived amidst a political culture geared towards community-based ventures, at a University which took centre stage in students’ lives. Today the University has more than tripled in size, far fewer students can afford to live close by, part-time jobs are an increasing necessity, contact hours are scant, and timetables are more individualised than ever. As is inevitable, things have changed. However, as we find ourselves in an era in which people are increasingly concerned about climate change and animal welfare, conservative governments are leading numerous powerful developed countries, and studies indicate a growth in loneliness and social isolation amongst Australians, I believe it is time to start thinking about how we can effect a renaissance of the Food Co-op by adapting it to suit the needs of contemporary life.

During the semester, The Food Co-op offers tasty, ethically sourced lunches and bulk food at cheap prices. To learn more about how you can get involved, swing by for a chat when the Co-op is open or email. Like the Facebook page for updates.

This project was produced as part of the third-year History capstone subject, HIST30060 Making History.

Special thanks to Alison Caddick and John Wiseman for sharing their stories.

One of my treasured memories from my time at Unimelb was shopping at the co-op. This is such a great article well done.