Why I Study History and Philosophy of Science: A Student Reflection

Samara Greenwood is a graduate student in her third year of History and Philosophy of Science (HPS). What began as a side interest quickly developed into a passion. In this personal piece, Samara reflects on what attracted her to HPS, what keeps her interested and her plans for the future.

Where I started

I began studying History and Philosophy of Science at the start of 2018 as a mature-age student. I hadn’t intended on coming back to study. Many years ago, I completed a gruelling master’s degree in architecture before going on to launch a successful practice. The idea of moving from professional in one field to beginner in another was not especially appealing. However, after health issues prevented me from continuing my practice, I thought I’d dip my toe in. I began tentatively, enrolling in a single subject through the University of Melbourne’s Community Access Program.

From my first HPS lecture I was hooked. The subject was God and the Natural Sciences and, within the first hour, I found myself excited by this new way of exploring the world. In particular, I was attracted by the interdisciplinary nature of HPS at the university. Instead of looking at complex topics through any single lens, we were encouraged to explore several perspectives. Indeed, it seemed no reasonable view was off the table.

For example, to explore the complicated relationship between science and religion, we examined the work not only of historians and philosophers, but also of theologians, sociologists, anthropologists, neuroscientists and cosmologists. All forms of knowledge building were treated with respect, and we had two wonderfully contrasting lecturers, one an agnostic/atheist historian of science with philosophical leanings and the other an Anglican minister and theologian with a PhD in physics (I know, what a combination!).

By closely studying historical episodes, such as the Galileo affair or the rise of Darwinism, as well as contemporary disputes such as those surrounding the origins of the universe, we picked apart any simple idea that science and religion are always in conflict. Instead, we discovered a far more nuanced and interesting relationship. After the subject ended, I found myself craving more. I enrolled in another single subject before taking the plunge into a Graduate Diploma of Arts majoring in History and Philosophy of Science.

What keeps me coming back

So far, my studies have ranged across the fascinating spectrum of topics that make up HPS. I have enjoyed exploring the history of science and society in the subjects From Plato to Einstein and Magic, Reason, New Worlds, classic philosophy of science in Science, Reason and Reality, contemporary issues of science and gender in Sex in Science and the way science evolves over time in The Dynamics of Scientific Change. Next semester I look forward to my first serious foray into social studies of science in Trust, Communication and Expertise.

My love for the multi-disciplinary nature of HPS continues to grow. I value how engaging with topics from several perspectives forces me to continually examine, expand and even completely reconfigure my old ways of thinking. I find I come away from each subject with a far richer and more sophisticated understanding than any single focus could provide. On the flip side, attempting to wrap my head around so many different (and often difficult) perspectives can also make my brain hurt!

I also love meeting fascinating people from diverse backgrounds, and the stimulating discussions that inevitably follow. As one of my lecturers is fond of saying, HPS is for people who are interested in everything and I have certainly found that to be true. I have met students (oh, and yes academics) with expertise in not just history and philosophy, but linguistics, biology, technology, gender studies, physics, archaeology and psychology, to name just a few. Needless to say, I am never bored.

What I hope to do next

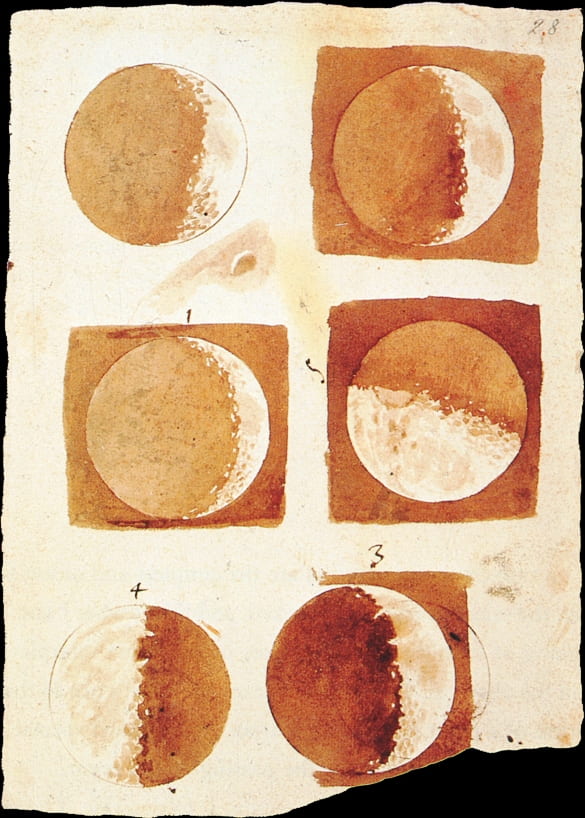

Through my studies I have developed an interest in those aspects of science that aren’t traditionally valued or even recognised. In particular, I find it fascinating that manual, creative and visual skills have always been central to scientific practice and yet are so often downplayed. Galileo, for instance, was deeply engaged with manual and creative arts. His interests included drawing (he even applied to become a teacher of artist’s perspective), instrument design (including the telescope, of course!) and the design of military fortifications (which he taught to private students). His scientific accomplishments drew heavily from these practical and creative experiences.

Another of my favourite historical figures is the so-called ‘father of neuroscience’, the late nineteenth to early twentieth-century neuroanatomist Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Cajal had early dreams of becoming an artist, but his father was adamant he follow a scientific career. Over time Cajal found his artistic skills were invaluable to his investigation of the physical structure of the brain. I particularly love his recognition that detailed sketching “forces us to examine the entire phenomenon, thus preventing the details that commonly go unnoticed in ordinary observation from escaping our attention”. Over his lifetime, Cajal is estimated to have completed more than 5000 drawings of neuronal matter, with many of these (very beautiful) drawings still valued by scientists today.

Building on these historical studies, I have also become interested in contemporary developments that recognise the role of arts-based skills in scientific innovation. Here I am thinking particularly of the rise of STEAM initiatives in science education. In these programmes, the teaching of STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) is combined with arts-based practices (such as drawing, design and non-routine thinking) to better equip students with the variety of skills required to solve contemporary problems. In the future, I hope to further research the role of craft skills in scientific development.

However, in the midst of the current COVID-19 crisis, I’m doing much the same as everyone else. I’m attempting to simply focus as best I can on what needs doing now while keeping my family safe. While the transition to online learning has been rapid, I’ve found our teachers have done a fantastic job in making the change as smooth as possible. I know they have put in remarkable hours to make this possible, and I for one am grateful. If nothing else, keeping up with challenging coursework provides a valuable distraction in such uncertain times.