Chinese-Australian Perspectives on the Pandemic: A Personal Reflection

History PhD candidate Luke Yin was on a research trip to China when the news of the COVID-19 outbreak was first made public. Returning to Melbourne in February 2020, he has been in a position to witness the pandemic from both Chinese and Australian perspectives. In this piece, he shares his reflections on how these events have made him look differently at both his country of origin and his adopted home country. He also shares his thoughts on the need for a shift in attitudes when it comes to international students at Australian universities.

At 10:00 am on 23 January 2020, I was lying in bed in a hotel in Shanghai. This was a lazy holiday morning, two days before Chinese New Year, at the tail end of my research trip working in a series of archives across the country. Suddenly, my phone chirped; an automated message informed me that “Wuhan will close down all its external transportation channels by this afternoon.” That’s all it said. No specific time, no sense of how long this shutdown might last, and no explanation. I knew immediately that something serious was happening.

A bit of background context about myself: I was born in China and have been living in Melbourne for ten years now. I travel back and forth regularly to visit family, but I became a permanent resident of Australia a few years ago. I’m currently writing a PhD thesis on the history of treaty ports in China at the turn of the twentieth century.

A Research Trip to China

In my memory, everything about the start of 2020 is fresh but, at the same time, surreal. In early January I travelled to Tianjin, a municipality next to Beijing, in Northern China, to carry out a week of archival research at Tianjin Municipal Archives and Tianjin Library. As its name indicates, COVID-19 started spreading in 2019, in December, if not earlier. But in January 2020, it seemed as though no one in China really cared (or was aware of) the imminent catastrophe. When I recall my time in Tianjin, it makes me angry to think about all the people exposed to risk on the city’s public transport system, for example, while the government and the media stayed silent about the epidemic. “Those doctors who spread false rumours about SARS coming back; all of them have been put in jail”, is one comment I remember hearing on the snow-covered streets of Tianjin in the first week of January

I spent most of my time in Tianjin either at the library or the archives, where I worked on transcribing manuscripts and government documents (taking photos is not permitted at the archives). By this time, the topic of what was then called ‘Wuhan Pneumonia’ (wuhan feiyan 武汉肺炎) had started to crop up occasionally (COVID-19 would become the official name several weeks later). But nobody was really concerned about this.

My stay in Tianjin was followed by a tour around three treaty ports whose history I work on: a brief stop in Nanjing, then a week in Shanghai, and a few days in Hangzhou. As a result, I spent a lot of time in January travelling around China on high-speed trains. Again, I blame the government for not telling me anything; had I known the situation, I would at least have taken some precautions. But no information was made public until almost the last week of the month.

Before the Wuhan Lockdown, the central government of China repeated over and over again that the new virus was “preventable and containable” (kefang kekong 可防可控). Again and again, the government sent out the message that this was only a regional incident that would be over in a few weeks, if not a few days. Later, within two weeks after the start of the lockdown, the Wuhan government and the central government started to blame each other for having failed to take immediate action.

The mayor of Wuhan claimed that he had reported the outbreak to the central government back in December 2019; under the law, he had been forced to wait for central government approval before making the news public. Given the non-transparency of the Chinese political system, we may never learn the full story regarding the decision making in the early days of the outbreak. One thing is certain: the mishandling of the outbreak can be attributed to structural failure of this highly centralised system and all the constraints that it imposes on local government autonomy, and in turn, this has only further eroded public trust in the authorities.

For me, the unfolding of the pandemic in China brings to mind the classic study by the American sinologist Philip A. Kuhn, Soulstealers: The Chinese Sorcery Scare of 1768 (1990). In this work, Kuhn analysed three different storylines created around this event: the version concocted by the officials sent out by the Emperor to investigate the scare, and who did their best to hide the real story from him; the version held to by the Emperor, who believed firmly that the whole phenomenon was an attempted coup in disguise aimed at overthrowing his rule; and the version according to the people, who were the only ones that really believed in (and actually cared about) the ‘sorcerers’, and who would do anything they could to protect their families from this perceived threat.

In today’s China, too, the Wuhan officials, the central government, and ordinary Chinese people, all have their own perspectives on the COVID-19 outbreak. After long exposure to government propaganda, some people are starting to believe that the government deserves praise for successfully containing the outbreak. But younger generations hold rather different opinions. For example, in February, three mainland female intellectuals (all in their 20s) and one Beijing University historian, Luo Xin, uploaded a podcast on Chinese social media condemning the government action of shutting down Wuhan. Now censored in Mainland China, it can still be viewed on YouTube (in Mandarin). The logic is clear: if the government does not know how to treat individuals equally, and if the government never recognises the fact that ‘humans are all the same’, we (Chinese) might learn nothing from this history we are experiencing right now.

One interesting feature of the Chinese media coverage of the outbreak is the figure of Zhong Nanshan (钟南山), a prominent Chinese pulmonologist and doctor who had been a leading figure in China’s fight against the SARS outbreak in 2003. In some ways, we might think of Zhong as a kind of Chinese version of Dr Norman Swan, the physician and ABC health reporter whose commentary on the pandemic has attracted a huge following in Australia, as an alternative source of trustworthy information. In the case of Zhong, however, his status as the ‘nation’s advisor’ (guoshi 国士) in the epidemic is at least in part the result of a state-sponsored media campaign. Zhong’s influence in China is also, without doubt, incomparably stronger than Dr Swan’s in Australia. Zhong’s name occupied Chinese media headlines almost 24/7 in the first few weeks following Wuhan’s shutdown.

Zhong visited Wuhan on 19 January; shortly after his visit, the Wuhan lockdown was announced. According to the official narrative, the central government took this decision in deference to Zhong’s authority as an expert on respiratory disease. It seems clear that the saturated media coverage of Zhong represented an attempt to shift public attention away from the government’s failure to contain the virus, and to focus on something ‘positive’ (zhengnengliang) instead. In the case of Zhong, this was extraordinarily successful; ordinary people fueled the cult of celebrity forming around him by sharing social media stories with headlines like ‘84-year-old Zhong Nanshan Still Works Out Every Day’, and featuring images of a muscle-bound Zhong lifting weights. Zhong enjoys genuine popularity; many Chinese people have found in him a voice of authority whom they are willing to follow without hesitation.

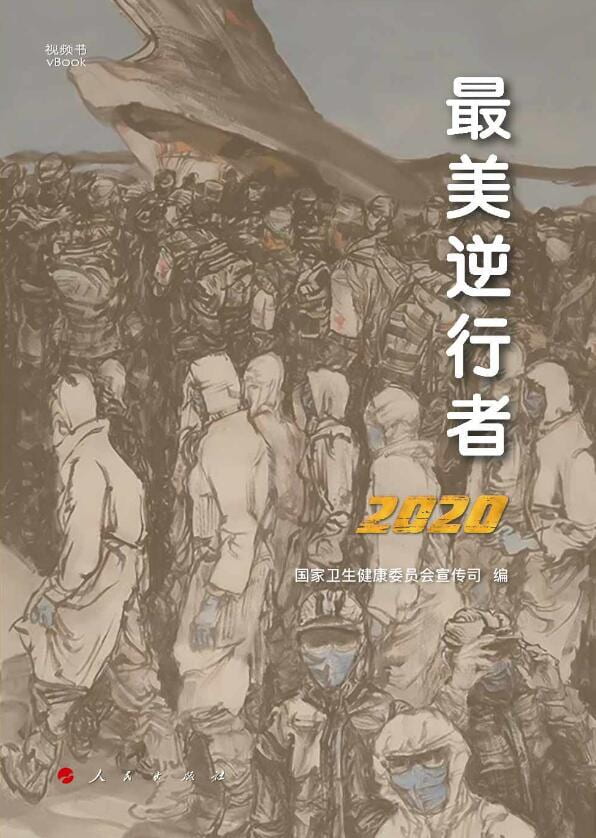

Simultaneously, there were media campaigns focused on the heroism of medical volunteers heading to Wuhan from elsewhere in China in late January to help fight the virus. These doctors and nurses were called by the state media as ‘those who walk backwards’ (nixingzhe 逆行者), indicating they were heroes who chose to go to the epicentre of the outbreak while others were running away from it. The message was clear: now was not the time to ask questions about government failures and responsibility for the outbreak; now was the time to rally together – and the country was in safe hands.

What happened in Wuhan, the official attempts to hide the outbreak, at both the local and the central level, and their consequences for Chinese and their families at this most important time of the year, gives us all good cause to condemn the Chinese government. What I would like to focus on here, however, is how these events have shaped the ways in which many Chinese people in Australia have experienced and responded to the handling of the outbreak in Australia.

The outbreak in Wuhan and Hubei Province included many shocking stories of human suffering and state failure. One of the most well-known was the case of the ‘cookie boy’, as he’s known on the Mainland Chinese internet. This boy was discovered home alone in late February 2020, together with his grandfather’s corpse. The boy had obeyed his grandfather’s last words, to stay inside because of the virus, and had survived on cookies alone, until volunteers eventually found and rescued him.

Another emblematic media image from the crisis was the footage of a girl in Wuhan, running behind the hearse of her dead mother, crying and screaming, in early February, as the death toll in the city surged. And then there was the story of the Hubei truck driver who was stuck on the highway to Wuhan after the shutdown for 47 days after the lockdown because all the roads to Hubei were blocked. The police discovered him in mid-February in Shanxi Province, where he had been eating dry instant noodles for a week because he could not find any hot water. The first sentence he said to the police was, “I’m so tired”. On 16 March 2020, he was finally allowed to go home.

A new story was unfolding as I wrote this piece, in March 2020, when 377 construction workers brought to Wuhan to build a new hospital for COVID-19 patients, were banned from returning home after several of them tested positive for the virus. The workers have been left stranded, with only part of the costs of their temporary accommodation covered by the government, and no certainty on what their future fate will be – and this despite the special status of the working class, enshrined in the PRC’s constitution as the ‘leading class’ under the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ (gongren jieji lingdaode wuchan jieji zhuanzheng 工人阶级领导的无产阶级专政).

Blanket censorship of these stories of state neglect and shocking human suffering is not possible in the age of the internet, and Chinese people around the world were glued to their phones in January and February 2020, mesmerised and horrified by the scale of the unfolding disaster. For many Chinese people, including myself, this experience made it especially difficult to watch what we perceived as a shocking failure to prepare for the coming pandemic on the part of the Australian government, as the prospect of an Australian outbreak drew ever closer.

Back Home in Melbourne

On 15 March 2020, the Victorian state government declared a state of emergency, and announced that ‘tougher measures’ were to be introduced to the community. Bafflingly, however, the streets of Melbourne were still busy. This was hard to understand. In Mainland China, when the government announced ‘extreme measures,’ they meant what they said. In Wuhan and all nearby cities, the military was involved in the daily administration of the city: it didn’t matter if you had fever or not, everyone (with the sole exception of those working in essential industries such as health-care) had to self-isolate at home for two weeks; and then for another two weeks – with the end date unpredictable. (At the time I was editing this article [8 April 2020], Wuhan officially lifted its lockdown after 76 days. Well, this is some good news.) A famous Wuhan film director died together with his parents and sister, all in a single week. We may never know how many families in Wuhan went through similar tragedies. Yet family members were not even permitted to view the body when a loved one died; the body was cremated immediately to avoid further spreading of the virus. To the PRC government, this is a war, and to claim an ‘absolute victory’ the virus needs to be contained and be “killed by extensive isolation” – there is no second option.

There were other aspects of the Australian response to COVID-19 that many Chinese found difficult to understand too. One of the most obvious differences has to do with attitudes towards the wearing of protective facial masks. Residents of Mainland China, Hong Kong, and many other East/Southeast Asian countries – all the countries that went through the 2003 SARS epidemic – have long been instilled with the idea that wearing a mask is a responsible and sensible, indeed an essential measure against respiratory disease. People wear masks when there is a chance that they might be ill, in order to protect others. This ‘mask culture’ is a legacy of the trauma of the 2003 SARS outbreak.

I have my own dim childhood memory from that time; I remember dreaming of a long, empty school corridor; it was cold, and somehow eerie. I was trying to find the way out. Suddenly my mom woke me, and took my temperature with a forehead thermometer gun. This was the first time I’d seen this device, but it would become all too familiar, as children’s temperatures were monitored constantly for months on end. Even today, in Hong Kong, school children report their temperatures each morning, and every family keeps a stockpile of masks in case of a fresh outbreak. The SARS epidemic has also left a deep mark on the collective memory in Mainland China – it may even be that the fear of the possible consequences of reactivating this memory lay behind the authorities’ initial attempts to cover up the Wuhan outbreak.

It was only when I returned to Melbourne on 27 January that I discovered that the primary measure taken by Australians confronting COVID-19 was (in line with the WHO advice) frequent handwashing and the use of hand sanitiser – a rather strange method, in the eyes of Chinese mainlanders, for a virus mainly transmitted through coughing and sneezing. Australians in general can tend to find the sight of a face mask off-putting, and they sometimes even misread a mask as indicating that an individual is a carrier of the virus, rather than being a sign of concern and care for others.

What COVID-19 Means for International Students and New Chinese Immigrant Communities in Melbourne

When people think about Chinese students or recent Chinese immigrants in Australia, many might think of a rather stereotypical image. It is often assumed that they come from Mainland China. But the reality is much more complicated. There is a huge amount of diversity in this community. There are Chinese from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and other Southeast Asian countries such as Singapore and Malaysia. We might also include here so-called ‘ABCs’ – Australian-born Chinese, who may not even speak a Chinese language or ever have left Australia. But perhaps it’s even more important to realise that students who are from mainland China represent a far from monolithic or homogenous group. They often speak different local dialects – for example, my partner and I speak Shanghainese, which is completely different from Mandarin, the official language. These differences create gaps linguistically, as well as culturally, between members of the ‘Chinese community’ in Australia.

Of course, I can’t claim to speak for all Chinese students or recent Chinese immigrants. But I would like to share some reflections on the personal experiences of a few close friends. Let me start with my own partner, a secondary school teacher and a new immigrant to Australia. She’s from Shanghai and like many Mainland Chinese immigrants, she has been extremely worried about the development of this pandemic. There’s one more reason for her to worry: she’s the head of the international student program at her secondary school. In the first week of April alone, three of her Chinese international students bought tickets to go back to Mainland China. My partner’s workload has increased dramatically since the crisis began. In many cases, where students are living in homestay, tension has arisen between the host family and their student lodgers, especially when there is a significant language/cultural barrier. My partner is also responsible for liaising with Chinese students’ parents, all of whom have become extremely anxious about their children in Melbourne: while the situation in China has stabilised, infections elsewhere across the world are surging. School holidays began on the last Monday of March, but not for my partner. Due to the time difference between China and Australia, she was working through the night, fielding at least a dozen phone calls a night, as well as being on standby in the daytime to handle conflicts with homestay families and medical and other crises as they arose. She never complains, and hasn’t asked for extra pay for her work. Her commitment is to helping the students who need her.

Then there is a friend of ours, Miss Wong, a student from Hong Kong who is studying at the Australian Catholic University in Melbourne. The language we have in common, and that we use for chatting with one another, is English. Cantonese is Miss Wong’s mother tongue; she is also currently learning Mandarin. She accompanied me for part of my trip to China in the first two weeks of January (for her, this was a vacation). As my companion, she was the one always nagging me to wear a mask on the train – she doesn’t trust the Chinese government. We’ve been working together on a non-academic book introducing the cultures of Mainland China and Hong Kong following last year’s mass political protests in Hong Kong. We want to give some our own insights into the perspectives of both sides and to help establish a connection between two communities. The book project has been set back by the COVID-19 outbreak, but I hope that we’ll pick it up again soon.

Another friend, Miss Peng, is a young woman from mainland China, working for a local accounting firm in Melbourne. After visiting family at home in China, she returned to Melbourne in early February. Like many of my Chinese friends and acquaintances in similar situations, she followed the Australian government’s directives to the letter. She self-isolated for 14 days, without leaving her house even once. Friends dropped off groceries to her doorstep during this period; an excellent cook, she kept herself busy devising culinary creations which she shared on social media.

Another friend, Miss Jiang, is from South China; she has been in Australia for about five years, and works for a Melbourne cosmetics company. She found the early stages of the crisis here particularly stressful – at her workplace, it took a long time before many of her Aussie colleagues grasped the severity of the situation. For weeks into the crisis, her workmates were inviting her to come out partying, seemingly oblivious to the danger. Media stories about people defying government instructions, for example, the mass gatherings on Bondi Beach in March, only added to her anxiety.

Many international students have had to make agonising decisions in recent months. Our housemate, who is from Mainland China, has been torn between going back home to be with her family in China and staying on here. She eventually decided to stay for fear that if she returned home she might never have a chance to come back to complete her studies. Another former housemate, from Wuhan, was unable to return to Melbourne after a trip home for the summer break, due to the travel ban. Her studies have been completely thrown out by the crisis; she has had to defer the semester, and at certain points she has considered giving up her Australian degree altogether and continuing her education at a Chinese university, since there is still so much uncertainty, with the end-date for the travel restrictions unknown. Other Chinese friends too were unable to re-enter Australia to resume their studies this semester. Some of them spent large amounts of money and effort trying to return – a few travelled as far as Thailand before being turned back as a result of the Australian government’s new measures.

It has been a distressing experience to watch how all of this has been depicted in the Australian media. All too often, Chinese students have been stigmatised as the source of the trouble and as potential carriers of the virus. They have been the target of the ugliest forms of xenophobia and racism. As the pandemic has unfolded, it has driven home to me the fact that Chinese international students are one of the most vulnerable groups of people in this global crisis, but no one seems to hear their voices – it’s rare for them even to have the chance to be interviewed as part of the media coverage objectifying them. To my great disappointment, on 6 April the Australian government asked international students to ‘go home’ despite the fact that the borders of many of their home countries are closed.

Once an international student and now a new immigrant to Australia, I empathise with international students and the difficult situation in which many of them now find themselves. Only a very small few have managed to raise their voices publicly in Australia so far. Ultimately, however, if international students are to be empowered, then it will be vital to find ways of connecting with them – this is a problem that the Australian educational industry ought to be reflecting on very seriously. This shouldn’t need to be said, but alas, I fear that it does: far from being mere ‘cash cows’, international students are just as intelligent, creative and individual as domestic students, and they deserve to be treated equally – everyone in the Australian community will benefit in the long run from this.

Some Final Thoughts

In Australia, on my return from China, I was hoping to find a place where I could, in a sense, start the year 2020 all over again. I soon discovered that it is impossible to ‘restart’ anything: nowhere on this planet is safe now, not only from the virus itself, but from the rising wave of xenophobia. Donald Trump continues to insist on calling COVID-19 the ‘Chinese virus’; meanwhile, in China, claims that the virus originated in the United States are also gaining traction. Identifying the origin of COVID-19 is important, but it should not be the main focus of public attention, and now is not the time for political squabbling on the international stage. What we really need to do right now is to establish a way of long-term thinking – something historians are particularly good at. If we look back to history – to the Black Death, the Spanish Flu, HIV/AIDS, SARS, H1N1 – we know that the next epidemic is inevitable and that it could happen anywhere and at any time. The real question is how we are going to cope with the profound changes that each epidemic brings to how human beings live on this planet.

We need now to think about COVID-19 and to think hard what we need to do to adapt to this change of social habits that is going on around us. Isolation, and sometimes, solitude, gives us a great chance to contemplate and reflect. We might choose to spend more time with our families (whether in-person or remotely), or to slow down our busy schedules so as to cherish something or someone we have taken for granted for too long. A book, penpals, Zoom-pals – I don’t have an answer yet. But I would love to devote my time to working on projects for future books, and exchanging thoughts with many more people in the near future. We are lucky to be in a place like Melbourne. And with hope that things are getting better each day, I’m confident in the potential for change in our community which the future generations will remember.

Jiyuan (Luke) Yin is a PhD candidate in History. His doctoral research concentrates on the urban history of treaty ports and everyday life in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century China, specifically in relation to social and cultural interactions between foreigners and Chinese. Luke is interested in historical topics around gender and sex, global immigration, and travelling. Luke is a member of the editorial team for the Melbourne Historical Journal, and also currently sits on the committee of the History Postgraduate Association.