Empowering Communities through Shared Learning

For the last nine years, conservator and Grimwade Centre PhD candidate, Sophie Lewincamp, has been investigating how conservators can better engage with community knowledge in a productive and equal way. Combining extensive on-the-ground experience with academic research and critical reflection, Sophie has developed a new community engagement framework called the Tiered Contact Zones Model. In this interview with Samara Greenwood, Sophie discusses her career in cultural conservation and how both practical hurdles and personal reflection informed her PhD thesis.

How did you first come to study cultural materials conservation?

I first studied at the University of Canberra. When I was looking to study conservation, it was the only course in Australia. The degree appealed to me because it wasn’t purely science and it wasn’t purely arts.

I applied, knowing it would give me a good grounding in a lot of things. At the time, the University of Canberra course was a three-year undergraduate degree and you had to do a year’s worth of chemistry. I knew that would springboard me to something else if I found it wasn’t exactly what I wanted to do.

There are so many cultural institutions in Canberra and they were always very supportive of conservation students. They would have little contracts – rehousing things, surveying collections. That really cemented things for me. I was already working in industry and I really enjoyed it.

While I was studying, I did contract work at the Australian War Memorial, the National Library of Australia, and the National Gallery of Australia. Then I got some longer-term contract work at the National Library. I specialised in paper conservation, but the Canberra Uni course gave a really good grounding in all of the specialisations, just like University of Melbourne does.

How did you end up studying and working at the Grimwade Centre?

After the National Library I completed an 18-month fellowship at the Library of Congress in Washington DC, where I researched the inks and pigments of tenth- to twelfth-century Qur’an parchment fragments. It sparked an interest in Middle Eastern and Islamic collections.

I was working back in Australia when a Middle Eastern Manuscript Symposium came up at the University of Melbourne. I came to Melbourne to present a paper and got to see the University’s collection. For a while, the thought sat in my mind, “I’d love to look at that collection.”

I ended up as lab manager at the National Library for 18 months. I did love that job, the collection and the people. Career-wise, I was at a crossroads. The opportunity to research the University’s manuscript collection, one of the few in Australia, was too great to pass up.

One day, I called the director of the Grimwade Centre, Professor Robyn Sloggett, and said “I’m thinking about doing some research on the Middle Eastern Collection, I’m thinking about coming to Melbourne.” She said “Great”. So, I took leave from my job and moved to Melbourne in 2010. I started my master’s by research and got right into the collection, which is now in the Special Collections at the Baillieu Library.

The Middle Eastern Manuscripts Collection comprises about 190 manuscripts – some are two books sewn together, some are loose leaves. It has everything you could imagine: Qur’ans and religious teachings, dictionaries, grammars, lots of Persian love stories and some beautiful, illuminated manuscripts.

How did your work on the Middle Eastern Collection transform into a PhD on community engagement in conservation?

As the project grew, I started to think about what I wanted conservation to be for me. I was asking, what is conservation in the twenty-first century? I didn’t want to do analysis of the pigments for analysis’ sake. I began asking myself: what is the purpose? I can get an understanding of the collection, but who is it for?

Also, at the time, I started another project, the RSL LifeCare Museum Project. RSL LifeCare is an aged care village with about 1000 residents in Narrabeen in the Northern Beaches of Sydney and they were looking to understand their collection of war memorabilia. When collaboration began, they were mostly thinking about the conservation of items they considered vulnerable, like textiles. There was also mould, so they were very down in that level of detail. But as we talked more, we found this would be amazing as a more fleshed out student engagement project.

While, again, it started out as a traditional conservation project, I was thinking, “I don’t want us to come in as the experts and take over this space.” But just because we come and work within a community doesn’t mean that community engagement happens.

I began to realise I wanted the project to do more. Like the manuscripts, the collection was under-utilised and there were many opportunities for more engagement. That was when it became clear that this was definitely a PhD.

So how did you combine these two projects with research on community engagement?

I’d read lots about community engagement across the arts and cultural sectors. Often the literature spoke of how community engagement could seem tokenistic and how difficult it was to get public understanding of the project. Sometimes there was also discussion of how, day-to-day, you can work together with communities to negotiate power imbalances and, when someone is missing from the story, how do you pull people in? For both projects, those issues were important.

For example, in the early days of the RSL LifeCare project, when we asked questions of the residents, it was mostly them answering and then leaving. The early feedback was: “The students are the experts, we’ll leave them to do their work.” Our response was: “No, you are the experts too.” We knew there was such potential for two-way knowledge sharing, but it didn’t always happen that way.

So, I read about how to establish communities of practice. My catchphrase became: “No cup of tea is wasted.” You have to have 1000 cups of tea for people to feel comfortable with the ethos of participation.

For the Middle Eastern manuscripts, my partner found an article saying there was an Islamic Museum coming to Melbourne. I emailed them to introduce myself, saying “I know you’re building this museum and we have this collection” – slowly, slowly, building a connection with them and their community.

We ended up meeting with the Islamic Museum and some manuscripts went on display there. Together we picked manuscripts that fitted with the content of the museum they envisioned. Even at the time of building they knew they wanted it to be about the key things that Islamic civilisation has contributed to knowledge domains including astronomy, mathematics and medicine. After picking the items, we then worked together to do translations and write the labels.

We put forward that the collection was not the sole source of expertise; rather, the collaborative process was part of the knowledge journey of the collection. We gained new knowledge in collaborating on the labels, but we also really wanted the wider community to just know that the collection was there, to come and have a look. So, little bits at a time – start small, build the story and, wherever you can, talk about the research.

What did you end up finding through your PhD?

The question I asked was: how can I create a structure for community engagement in materials conservation that’s easy to work with in large management as well as right down in everyday detail?

I began by looking at the idea of contact zones which began in linguistics. When not everyone speaks the same language, how do people navigate the sharing of knowledge? The idea of contact zones wasn’t new, but I felt that the literature on this topic tended to neglect that real detail of on-the-ground negotiation. And that’s what I found I was needing in my own work.

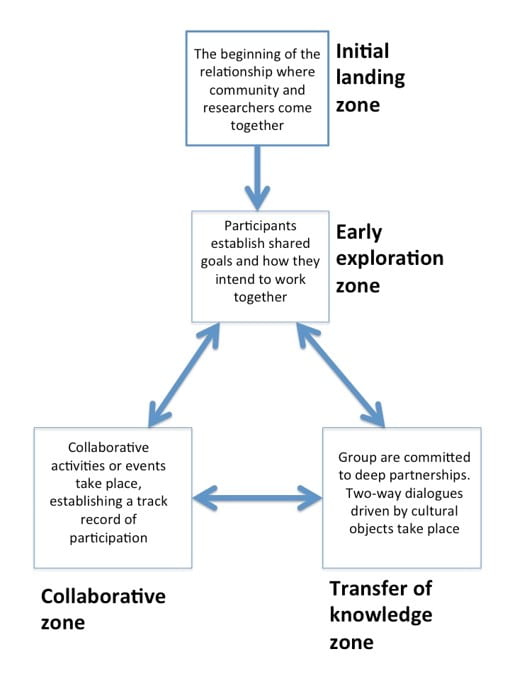

I developed the contact zones idea into a model of four ‘tiered’ contact zones. The first one is the ‘initial contact zone’ – the time and place where the groups first come together. The next one is the ‘exploration zone’, where we ask questions like: What does the collection need? What are our aims together? What are our shared goals?

Then there are two, more mature, zones: the collaboration and knowledge transfer zones. In the ‘collaboration zone’ we are coming together to do the work, and then the ‘knowledge transfer zone’ is where we actually see the two-way sharing of knowledge that we’re striving for. In this zone, everyone is more equal in the sense that we understand that ‘you know things’ and ‘I know things’, and we both want the story to be more complete by bringing those different forms of knowledge together.

When I began, I was tracking the process in linear form, but found that that didn’t work. You often need to go back a step when something isn’t working or something new comes up. The process circles back on itself.

With the RSL LifeCare project, at the beginning there were a few situations where knowledge was shared, but it wasn’t happening all the time. The structure told us that we needed to build more. So, I started to consciously create situations where we came together more often – more formal situations in which we could be more informal.

We created an ‘Antiques Roadshow’ approach. We would pick a few artefacts and invite the museum committee members and student conservators to sit around the table to share their knowledge or simply say what we saw or felt. It could be anything.

Someone from the air force might know that is a model of this particular plane and it flew in these kinds of conflicts. So sometimes, it just seems like the facts. But then, as we talked more, someone would say that they remembered reading or hearing something. Like, “My dad’s friend told me …” We were able to consistently produce more of that kind of conversation. And as these gatherings developed, people started to bring things along as well. We had ex-service personnel who brought photos, for example.

Student conservators contributed by demonstrating how we look at collections. They might say, “I can see how this has degraded here,” sharing the way we inquire about an object. I then began, in a casual way, to say, “Hey, we might call that social information” (or “historical information”, or “physical information”), to show how all these little bits of information come together to tell a richer story than any one kind alone.

While people don’t need to use all of the model, it helps you see the different kinds of engagement and what could happen in each of those zones. It highlights that we’re always going to need to check in to see how things are progressing and to adequately resource the process, both in time and financially too.

It also shows that not everything can be fleshed out in the beginning and mistakes will be made. For example, in one project a participant did something that broke a part of the trust, that wasn’t a collaborative decision. That will happen. So, what does it look like to rebuild?

When Robyn Sloggett first began the two-way collaboration between Melbourne Uni and the Indigenous communities of Warmun she said: “We will get this wrong, but we will get it wrong together.” I thought an awful lot about that.

How do you see your research fitting in to larger questions in academia?

Both of these projects allowed me to navigate the knowledge that we bring in our professional world and how we want the arts cultural sector to work. How do we give people the space to tell their stories as the ‘bosses’ of that knowledge with us, as academics, playing the supporting role?

The space needs to be more consciously created. When engagement isn’t happening in the way we envisage, we need to create situations which allow it to happen more consistently. It should be the normal way we work.

Terri Janke recently released a significant report about Indigenous engagement, saying that lots of individuals have been doing great work but it hasn’t become policy. Where are the policies? It needs to be top down to allow work to continue in meaningful ways and have people assert their authority over this knowledge.

As curators and academics, we need to stop and make sure our work does not become just our space and our tools. Traditionally, you come in, you are the contractors, you do the work, you hand it back over. The case needs to be made: “this is what it looks like when you have real engagement, when you empower people”. We all have expert knowledge. How can we come together to do things differently, to tell the bigger story?