The Truth Behind A Pirate Legend

Benito de Soto was a ruthless and violent pirate, but his story has been rewritten (and reimagined) over 200 years to create his modern rebel reputation. Dr Sarah Craze and Associate Professor Richard Pennell from SHAPS explore his story in this article, republished from Pursuit.

You may have already heard of the pirate Benito de Soto without realising it. He features on the blurb for the Australian Burla Negra Tempranillo with the description “inspired by the pirate Benito de Soto’s Spanish roots and uncompromising attitude”.

We know Benito de Soto was a real Spanish pirate, but “uncompromising attitude” is a very polite way of describing his vicious and murderous activities.

So, our research set out to unravel the mystery surrounding how a bottle of wine came to represent the sanitisation and mutation of Benito de Soto’s story.

A History of Violence

The short version of Benito de Soto’s tale is that he became a pirate when he and the crew of a Brazilian slaver, the Defensor de Pedro, mutinied in 1827 and gained control of the ship.

On 19 February 1828, off the island of Ascension [in the South Atlantic], they attacked a British ship, the Morning Star. Benito de Soto was their leader when they killed the captain, assaulted several crew members and raped the women passengers.

They then sabotaged and tried to sink the ship. Fortunately for the Morning Star, another British ship came across them a month or so later, then the crew and passengers managed to sail home to London.

But the pirates sailed on too.

After the Morning Star, they captured an American ship called Topaz and massacred the crew – then went on to ransack several other ships, releasing those onboard and the ships themselves, unharmed.

Eventually, they reached Pontevedra, Benito de Soto’s hometown on the Galician coast. They landed their booty and set off for Gibraltar in the Mediterranean.

On 9 May, Benito de Soto ran the Defensor de Pedro aground near Cádiz in southwestern Spain.

The Law Catches Up

The local authorities there soon arrested 17 of the crew, but not before two made their escape and fled to Gibraltar, which was a British military garrison at the time. One of the men disappeared; Benito de Soto, gained entry, but he was eventually arrested.

Working in concert, the British and Spanish tried the pirates separately. In January 1830, the British hanged Benito de Soto. The Spanish hanged and dismembered some of his pirate crew and imprisoned others.

Unusually, there’s a rich documentary record of all of this in English and Spanish that survives today, but very quickly these sources began to fade away from the narratives of the time.

Within months of de Soto’s execution, in plain view of the people of Gibraltar, the story began to mutate.

One of these stories eventually changed the ship’s name from Defensor de Pedro to La Burla Negra or, in English, The Black Joke.

Changing History

The first full summary of Benito de Soto’s story was written by British surgeon Daniel Wedgworth Maginn. Maginn interviewed both Benito de Soto and the Crown’s key witness, Andrew Beyerman, who was the Morning Star’s steward.

His account resembles most of the archival and press narratives, with two important differences.

The first difference is that the (unnamed) relief ship that came up on the Morning Star and provided assistance did so the day after the attack, rather than a month later.

And, secondly, the pirates attacked the American ship Topaz first, not the Morning Star. It never mentions the name of de Soto’s ship changing.

Maginn’s version of events appeared in the United Services Journal in 1830. It then quickly crossed the Atlantic to the United States, where it eventually appeared in The Pirate’s Own Book by Charles Ellms which survives online today.

In Spain, de Soto’s escapades were not remembered the same way.

The first supposedly historical version was actually largely the fantasy of one Spain’s greatest novelists, Benito Perez Galdos.

In the 1840s, Galdos wrote a supposed memoir of a young naval officer who had defended one of the pirates at the trial in Cadiz. Galdos made the young French pirate, Victor Saint Cyr Barbazan the centre of the story.

An 1855 novel El milano de los mares (The Kite of the Seas) recasts Barbazan as the hero of the story who killed his rival Benito de Soto and fled to Ascension Island with his lady love.

A correction only came in 1892, with the publication of the Spanish trial records by naval admiral Joaquin Maria Lazaga. None of these narratives mentioned La Burla Negra either.

The Black Joke myth became popular back in England when the independent scholar Philip Gosse produced The Pirate’s Who’s Who in 1924 and the History of Piracy in 1932.

He added several unique elements to Benito de Soto’s story, including changing the name of the ship to Black Joke and the attack on the Morning Star to 1832, not 1828.

Despite Gosse’s extensive collection of piracy books, including Maginn’s far more accurate version of events, Gosse instead drew The Black Joke from a volume of reminiscences by a very elderly seaman called Captain Henry Holmes, which was actually published in 1902.

Gosse’s compatriot in maritime history, Basil Lubbock, also picked up on this fabrication. Before long, The Black Joke story had spread into the British canon, re-emerging most recently in pirate history anthologies published in 2007 and 2008.

The translation of History of Piracy into Spanish in 1935 further entrenched The Black Joke myth in Spain and the ayuntamientos (or city councils) began to lay claim to the story.

The Modern Sanitisation

Benito de Soto came to be seen as a rebel against an unjust social order, like the pirates of the Caribbean a century earlier. His impoverished background, his brutalisation by his conditions and his connection to slavery were used to change his image to something like a swashbuckling hero, rather than a mass murderer, and the actual victims vanished.

But there’s no evidence of any social or political objective behind de Soto’s piracy. He really was just after riches. And The Black Joke version that is now the dominant narrative is largely based on accounts that later historians constructed.

Today, there are two streets in the Spanish town of Pontevedra named for Benito de Soto reportedly because the pirates’ gold surfaced (it was said) in both Pontevedra and Cadiz.

Galician political radicals made Burla Negra a symbol of opposition when an oil tanker Prestige sank off the coast in 2002. Musicians have commandeered the name to represent their anti-establishment views against the entrenched right-wing local government.

And then, in 2018, a South Australian winery gave the Burla Negra name to its Tempranillo.

The story of Benito de Soto’s transformation from violent criminal to rebellious hero is just one example of the way the romance and mystery of piracy is exploited for both historical and commercial interests.

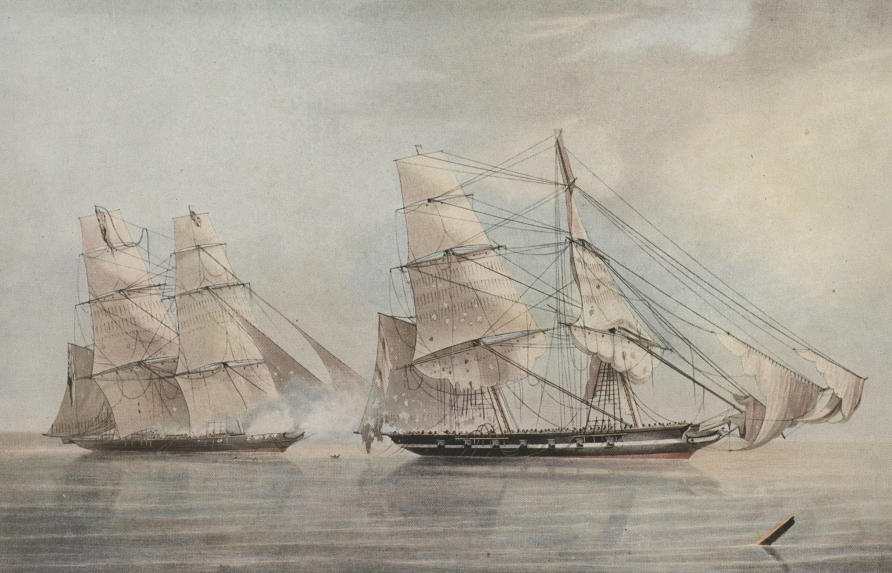

Feature: Illustration from The Pirates Own Book by Charles Ellms, 1837