Exploring the History of Piracy

In 2019 Dr Sarah Craze completed a PhD on the history of the 2008–2012 Somali piracy epidemic. Her study of this topic also explored historical connections to piracy in the Caribbean and the East Indies centuries earlier. In this interview with Dr Henry Reese, she discusses her work on this fascinating category of historical actors.

Sarah, when we think about piracy, we tend to think about the sixteenth-century Atlantic world or the Caribbean – the age of European imperialism, and the spread of multiple states westwards across the Atlantic. How does that earlier period connect to the twenty-first-century history of piracy in Somalia? How do we come to grips with this longer span of the history of piracy? How does it all fit together?

It doesn’t magically click together, but then, nothing in history does! Still, across the centuries there are important similarities and common factors that cause piracy to emerge in different parts of the globe. And the first and most significant is that all pirates must have a favourable geopolitical environment.

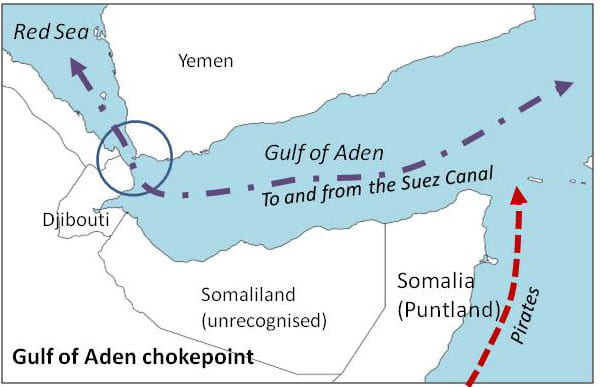

Thinking about geography first, pirates need a reliable and predictable stream of potential targets. One way to find ships is to hang around a ‘chokepoint’ – which is a fancy military term for a bottleneck. From an oceangoing perspective, chokepoints are formed by narrow channels between landmasses that force ships to isolate themselves from one another in order to pass through.

One of the most famous historical examples is the Straits of Gibraltar. This passage provides the only entrance to the Mediterranean Sea from the Atlantic Ocean, and it’s only 14 kilometres across. For centuries, the Mediterranean was a major trade route for European goods. This sea trade moved under sail and the narrow passage forced ships to group around the entrance to the straits to await the favourable winds and currents that allowed them to sail through.

These waiting ships created targets for sea-raiders, including the North African corsairs active around there for many centuries. These corsairs carried a patriotic-religious authority from North African rulers to attack enemy ships which hadn’t paid suitable tribute. Their enemies often considered them pirates but, strictly speaking, they don’t fit the actual definition of a pirate, namely, a sea-raider who carried no commission at all.

The corsairs would sail up from the south, and they’d be able to pick off the targets individually and chase them down, because they knew that they’d be trying to get through this channel to reach the Mediterranean trading routes.

In the Caribbean, there are lots of chokepoints. The Caribbean has a chain of islands that delineate the Caribbean Sea from the western Atlantic Ocean. These islands break up the clear expanse of water, and they forced trading ships through a predictable route to their island trading posts, dictated partly by the winds and the currents that pushed them through in a particular direction. Pirates would hide out on the other side of the islands, lay in wait, and then chase the ship down and attack it.

Another major chokepoint is the Straits of Malacca, between Indonesia and Malaysia, which is part of the shipping route from India to China. Indonesian pirates exploited the flow of traffic through here in the 1990s, and sometimes still do so today as well.

When it comes to Somalia we find a similar situation. Somalia’s northern coast is along the Gulf of Aden that connects to the massive amounts of sea traffic travelling to and from the Suez Canal every day. As you sail up the Gulf of Aden, you’re forced through the Bab al-Mandab Strait, which runs between Djibouti and Yemen. In order to pass through, the ships need to self-isolate, and that makes it easier for Somali pirates to pick off the merchant ships as they come through. So we find similarities in all these different cases.

Obviously, the geography hasn’t changed much over the years and most of these places no longer have problems with piracy. But, in addition to the geography, there also needs to be a political environment around the geography to allow piracy to occur.

The Caribbean in the late seventeenth and eighteenth century is a really good example of a highly favourable geopolitical environment enabling piracy to thrive. This period, from about the 1680s to the 1720s, is often known as the ‘Golden Age of Piracy’. In fact, there were pirates around long before this; the period itself encapsulates four separate periods of piracy – but it’s still a useful umbrella term for a period in which piracy was certainly flourishing.

During the Golden Age of Piracy, there were four dominant European colonial powers present in the Caribbean: the English, the French, the Spanish, and the Dutch. In this region, the sea-based aspects of the wars between these powers often played out through what’s called privateering – the authorised raiding of ships during wartime.

Privateering looked something like this: when war was declared, the king or the queen would create commissions, which they would distribute among private individuals who owned ships. They would say: you go out and raid my enemy’s shipping for me, and then when you bring back your cargo, I’ll take a cut of 10 per cent, and you can distribute the rest among your crew. This is how war was fought on the sea up until the mid-nineteenth century. Back then, navies essentially just transferred troops to places of war; engaging in combat was not their primary purpose, because there were privateers to do the fighting. This was a very decentralised, privately organised enterprise.

Now, the privateers would only be authorised to engage in these activities during wartime. And often, when the war ended, they were thinking: well, it’s pretty good pickings around here! I’m just going to keep on raiding and, legally speaking, this would turn them into pirates. A pirate was essentially someone who was raiding ships without a commission or in peacetime. In between the wars during the Golden Age, a lot of former privateers became pirates.

At this time, the individual authorities on the Caribbean islands simply didn’t have the financial resources, the personnel or the ships available to control illegal sea-raiding. A big part of the problem was that it was difficult to recruit people to pursue pirates. The navies suffered from a lot of the same issues that beset the merchant marine at that time. The pay was lousy, the crews were terribly mistreated, there were big problems with drunkenness and disease was rampant. So for obvious reasons, people were not really that keen on joining the navy.

Another problem was that authorities often profited from illegal ship-raiding proceeds themselves. There are a number of examples of Caribbean governors and authorities benefitting from pirate plunder. And naval commanders saw little financial benefit for themselves in hunting pirates down. They often decided it wasn’t worth the effort, so pirates were effectively allowed to keep on rampaging.

To confuse this situation even further, when the next war broke out – which it inevitably did – the colonial authorities would offer amnesties to the pirates to try to lure them back into legitimate employment as privateers. This is because the reality was that they were extremely highly skilled, accomplished sea-raiders – they were really good at their work! As a result, the benefit of having them working for you during wartime outweighed the nuisance they made of themselves during peacetime.

There were years and years of this back-and-forth between legal raiding and illegal raiding, with rulers on the one hand complaining that something needed to be done about the raiders when they were pirates, and then on the other hand, being perfectly happy to profit from the raiding they did as privateers.

The final phase of this Golden Age, after the end of the War of the Spanish Succession in 1714, is the one that most people associate with Caribbean pirates. Charles II of Spain failed to provide an heir to the Spanish throne, and after his death, this triggered a competition among the European powers. The resulting war hastened the decline of the Spanish Empire, which was increasingly unable to afford to maintain control over many of its colonial assets, including in the Caribbean. It was the years after this war that saw the rise of figures like Ben Hornigold, Blackbeard and Bartholomew Roberts – named pirates that still survive today in popular culture.

Iconic pirates!

Yes, absolutely.

The end of the war helped to bring them into being, but that wasn’t the only impetus. Another important catalyst for the explosion of piracy during this time was the ‘Great Storm’ – what we would consider a hurricane today – in 1715. It hit the Bahamas and sank a large portion of the Spanish treasure fleet which happened to be anchored there at the time. There was an incredible frenzy of piracy, which even the colonial authorities were participating in, because there was all this gold that had just sunk to the bottom of the ocean off the Bahamas, and everybody knew it, and everybody wanted to get their share.

At the same time, however, there were other men emerging who were frustrated by the way they were being mistreated at the hands of the sea captains. These men were starting to reject all forms of official authority like religion, sovereign authority, you name it – they weren’t interested in any of it; as far as they were concerned, they were authorities in their own right.

These men (and a few women) started raiding the ships that were trying to go after the gold. So they were operating entirely in their own interest – and it’s here that we find the germ of the popular idea of pirates as anarchists and rebels against authority. These were initially men who really just had no interest in listening to the colonial authorities’ pleas to stop, and the colonial authorities had no naval capacity to stop them at the time.

Overall then, in order for piracy to work operationally, you need an environment where you have not just the right geographical factors but also, at the very least, a weakness in the formal authority functioning at the time. It also helps if you have complicity in the piracy on the part of the authorities. These are recurring themes that connect together the different forms that piracy takes across time and space.

How does this connect to your own work, on the contemporary history of piracy in Somalia? Do the same ideas apply to this case?

Well, the piracy outbreak in Somalia began in 2007, and this happened in a country that had not had any kind of functional centralised state since 1991. There was no official army, no navy, no coast guard – nothing to stop people from hijacking ships. The standard narrative was that the state’s failure caused the piracy.

But the interesting puzzle about Somali piracy is that the state collapsed in 1991, whereas the piracy epidemic didn’t really begin until 2007. So there’s a large gap of time there that I needed to explain. You can’t just say: well, the Somalis were hijacking ships because the state failed – because if this was the case, why weren’t they doing it earlier? In fact, when we look more closely, we find that there were lots of things happening on the land that stopped the pirates emerging before 2007.

One of these factors was the presence of locally formed administrative structures in Somalia, and most notably a semi-autonomous region called Puntland, in the far northeast, the ‘horn’ part that gives the Horn of Africa its name. This is where many of the pirates came from.

Puntland developed in 1998. It was organised as a local effort by a group of elders, with the aim of finding some kind of peace. And initially it was quite successful, despite the fact that it had no real support from the UN or the broader international community, which had more or less washed it hands of Somalia after the disastrous humanitarian intervention in 1992.

The authorities in Puntland did manage to keep piracy to a minimum until about 2007. That year, however, Puntland suffered a whole series of crises: a drought; a terrible economic crisis; and a border dispute with neighbouring Somaliland. There was also the problem of al-Shabaab, a fundamentalist Islamic group that formed in Somalia around 2006, which was rising in the south and starting to press on Puntland (although at this embryonic stage, al-Shabaab was very different to the al-Shabaab that exists there now).

All of these problems absorbed the very meagre supply of security forces and financial resources that the authorities had, and as a result, compromised their capacity to control the Puntlanders. In addition, the Somalis considered the piracy a Western problem. They constructed a narrative that it occurred in retaliation to illegal fishing by foreign fishers and that their countrymen were simply defending Somali interests against Western incursions in their territorial waters.

Now, there is clear evidence that illegal fishing was a serious problem in Somali waters. However, in 2007 the pirates began hijacking cargo and merchant ships, not fishing vessels. This shift occurred because the multiple crises in Puntland had overstretched its already very limited security forces. Organised criminals realised there was nobody to stop them hijacking ships. They started to ramp up their piracy operations, targeting merchant ships that were obligated to pass through Bab al-Mandab Strait. So this is how the modern wave of piracy started – with the authorities’ lack of control over their citizens.

Thank you for that enormous summary of hundreds of years of piracy! It’s great to put it all in the same frame, and to think about some of the aspects that we might not usually associate with piracy: the importance of geography, and the economic motives.

Could you tell us a bit about your research journey? How were you drawn into studying the history of piracy?

Well, until about ten years ago, I think my experience of pirates was similar to everybody else’s. This really just amounted to having seen the Dread Pirate Roberts in the Princess Bride movies and Captain Jack Sparrow in the Pirates of the Caribbean. I’d seen Muppet Treasure Island, but I don’t think I’d even read Treasure Island!

At the beginning, I didn’t even know that Africa had a history of piracy. I was studying for a Master of International Relations at the University of Melbourne, and as part of that course, I needed to write a minor thesis, which is really just a very long assignment, and it needed to be on a contemporary issue. And I decided I wanted to do it on something to do with Africa.

Around this time, I happened to read an article in Vanity Fair magazine about the hijack of a French luxury yacht off the coast of Somalia in 2009. What I found really interesting about the story was just how business-like the whole operation was – the pirates had no interest in killing or hurting the people on this ship. This was purely about business.

This hijack lasted about six days, which is actually an extraordinarily short period of time for a Somali hijack. And while they were waiting for the ransom payment, the local Somalis were motoring to and from the boat, supplying food to the pirates. And all of this was being observed by a French naval ship that had just arrived and was just monitoring the yacht – the French ship was in radio contact with the yacht, but it did absolutely nothing to interrupt the hijacking process. And I found that really extraordinary. Then, when the ransom came, it was dropped by a chartered airplane, and the pirates collected it out of the water; they said goodbye to everybody on the yacht, who they had become quite friendly with, and they let the yacht go.

I found the whole thing really fascinating, and so I thought, well, I have to do this assignment – I’ll do it on Somali piracy! The university put me in touch with Richard Pennell, an Associate Professor in History, who I then found out was quite an eminent authority on piracy. So that was really lucky for me. And later, after I finished the assignment, Richard asked me if I wanted to do a PhD on Somali piracy, and it all started from there.

On the topic of Somali piracy: there’s a common conception, potentially a misconception, that Somali piracy is intimately related to al-Shabaab, and that piracy has funded Islamist insurgency in Somalia, potentially in Yemen, in other parts of East Africa. From what you’re saying, though, it seems to be a different problem. It seems that in fact these problems aren’t really connected in Somalia – maybe that says more about the way that the media covers Africa more broadly.

Yes, I’d agree with that. Somali piracy is predominantly perceived as a maritime security issue. But I take the historical perspective, which is to ask where this phenomenon actually comes from. There’s no question that it certainly is a maritime security issue, but at the same time, economic factors have always been a huge motivator for piracy.

Some of these issues are explored in a Hollywood movie about a Somali piracy hijack, from 2013, Captain Phillips, starring Tom Hanks. The film is based on a captain’s memoir of his experience of being captured and held by pirates for about four days before being rescued by the US Navy. In the film, they take quite a lot of pains to try to present the Somali side of the story. So the film asks: why are the pirates doing this? And the answer is: they’re desperate – they’re economically desperate people, and they don’t really have any other job prospects. You don’t make a lot of money fishing from a little skiff, especially when you’ve got illegal, massive industrial fishing ships off your coast scraping the sea floor, so there’s nothing left for you to fish anyway. The real Captain Phillips openly acknowledges this and doesn’t really blame the pirates at all.

There was also societal pressure for young men to engage in piracy within Somalia. Remember, the pirate leaders justified it as a retaliation against illegal foreign fishing. The financial rewards were viewed as compensation for protecting Somali interests, not criminal proceeds. In addition, if members of your clan engaged in piracy, it could be very difficult to resist pressure to join. The Captain Phillips film tried to express this and to show the story from those two different perspectives: the perspective of the sea captain in this horrible situation, and the perspective of the Somali pirates.

With regard to links to terrorism, I don’t think they were there at the time. One thing Captain Phillips emphasised after the hijack was that the first thing the pirate leader said to him was: “no problem; just business; no Al-Qaeda – we are not al-Qaeda”. Many of the pirates interviewed back then said that they personally thought the al-Shabaab guys were crazy. The pirates were insistent that they were just businessmen.

Fundamentalist Islam only came to Somalia around 2006 and it was quite far removed from the Sufi form of Islam the Somalis practiced, and definitely not typical for Somalia. The entrenchment of Al-Shabaab means fundamentalist Islam’s influence is far more widespread now, though, including in the government.

There’s also no evidence that anyone was hijacking ships deliberately to give the ransom to al-Shabaab. There is some evidence that al-Shabaab was taking a cut, essentially demanding protection money from the pirates. This is reflective of how al-Shabaab now is essentially run like a mafia protection racket in Somalia; in fact, it makes more money than the government. It’s quite entrenched now. And it’s very profit-seeking in its own right – something which people often don’t realise about terrorism. Back then, I don’t think the pirates and al-Shabaab were connected in more than just a peripheral, superficial way. The pirates certainly weren’t hijacking ships to fund terrorism – that was not happening.

Nowadays, it’s quite different. Look at it this way: if you’re just a regular guy who is hungry, doesn’t have a job, doesn’t have any money, doesn’t have any real prospects of acquiring any of this, then it might be very tempting to join al-Shabaab. Ten years ago you might have become a pirate but now there’s an organisation that can provide you with the financial and food security that your government can’t. Plus you would have grown up in a war-torn world, with easily accessible weapons. So I think what’s happening is that a lot of these young men are joining al-Shabaab not really because they believe in the ideology of it, but more because it at least provides a regular paycheck and food in their stomach, which is an extremely unfortunate and sad state of affairs for them.

That’s a really illuminating way to look at it.

My next question would be this: being a pirate is not an easy job – it takes quite significant skills to be able to manage what are often quite improvised craft and improvised weapons and to succeed against what are often much more advanced technologies. And so I wonder, does Somali piracy tap into a longer seagoing tradition in Somalia? There are very long-running maritime traditions in East Africa and the Indian Ocean world more broadly, and a long history of Arabic-speaking traders and slavers and administrators, you know, linking this whole world up together. Is there much connection there?

Actually, Somali pirates are probably one of the rare groups of pirates who don’t have much of a seafaring tradition! At least not when it comes to the guys who were engaging in piracy in 2008.

The Somalis are traditionally pastoralists, so their internal trade networks look inland and most of their settlements are inland, not on the coast. They do engage in fishing, but they do this because of the international market for fish. They don’t eat fish themselves; in fact, they’re quite fish-averse, and they often don’t trust people who eat fish. There’s even a Somali proverb about this, roughly something along the lines of ‘speak to me not with your fish-eating mouth’! And there have been a lot of complaints from Somali pirates who were held in prison in the Seychelles and were unhappy about being fed fish there. So their trade centred on their livestock and they dealt with Arabic traders for centuries.

The Majeerteen sub-clan, who were one of the major players in Somali piracy, do have a tradition of sea raiding. This was not raiding ships at sea but raiding European shipwrecks that crashed onto their shore. The Majeerteen are one of the largest sub-clans in Somalia; in fact, they’re bigger than some of the full clans. Today, this gives them considerable political power in Puntland and in the federal government.

Back in the mid-nineteenth century, the Majeerteen’s lands were along the northern Indian Ocean coast, where the triangular tip of the Horn is. Every summer, a whirlpool occurs off the Horn. In the nineteenth century when the foreign sailing ships would come around that point, they would often get caught in the whirlpool, and that would cause them to get wrecked on the shore. So, whichever members of the Majeerteen’s sub-lineages happened to encounter a shipwreck would then raid it and receive the financial benefit of it over the other lineages. And over time, they would use these proceeds to increase their political standing within the sub-clan.

It became such a problem that by the late nineteenth century the British offered the Majeerteen a treaty that authorised the British to pay an annuity to the Majeerteen to stop them from killing British shipwreck survivors. This proved quite effective. Somalis were quite entrepreneurial in the way they approached this foreign engagement.

So, historically, there was certainly this idea of using raided shipwreck proceeds to gain political power, participating in trade with Aden, and with Arabic traders. But they don’t really have a strong tradition of seafaring or sea-raiding like the Caribbean pirates that we know about.

What the Majeerteen do have in their lands is access to large expanses of ungoverned space. In the Caribbean era, ungoverned spaces were isolated islands with fresh water, maybe some wood, other resources that pirates might need. In Somalia, long stretches of empty beach along the Indian Ocean coastline fulfil this purpose. The government structures of Puntland are located quite far inland – the capital Garowe is about 300 kilometres from the coast. So it’s not like Australia, where the vast majority of the population clings to the coast. They’re quite an inland-facing society and their trade is very much more about the movement of livestock. And so they have all this beach – masses of isolated beach, and caves to hide in. These were used to shelter, regroup and supply the pirates without any kind of oversight from authorities.

We tend to think about historical pirates as white European men. But obviously, the picture is far more complex here. I can’t help but think of Meg Foster’s recent work on bushrangers who weren’t white or male. It’s amazing work that expands our picture of often iconic figures, and helps reveal some of the complexities and the diversity in pasts that we think we know very well. So do you have any thoughts about piracy, race and gender?

There’s no question that piracy was very much a male-dominated world. But there were undoubtedly women involved in it, and especially on the land, as part of the support network. In Western culture, there were definitely female pirates at sea. Probably the most famous are Anne Bonny and Mary Read. And they’re often presented as these feminist rebels against the oppressive society of the time, which was very much in keeping with the way all the pirates of that time were presented. But, at the same time, they are sometimes presented as subservient to their male partners on board the ships. It really depends on what book you read about them.

They were certainly real people, because there are records of their prosecutions, but there’s not a lot of information about them specifically. They definitely avoided execution because they were women – I think they even faked pregnancies to get out of hanging! It’s quite possible that they rebelled against societal oppression and followed their partners into piracy. I don’t think they’re mutually exclusive.

I can’t help but think of that image from Bertolt Brecht’s play The Threepenny Opera, where one of the characters imagines herself as ‘Pirate Jenny’, you know, where this trope of freedom that she can imagine for herself involves her being a pirate!

It really goes to show just how limited the choices were back then. A life at sea was a very hard life even just for the regular seaman. So I guess this is why a lot of these pirates were saying, ‘Let’s just be free and make our own choices’, because there were no other opportunities to do that at the time.

There were definitely more women in piracy on the South China coast. I’ve always enjoyed the fact that the most successful pirate of all time was a woman, named Ching Shih – there’s a great section about her in a book by Dian Murray.

The race issue is interesting, because there’s definitely evidence that pirates sympathised with African slaves. And they felt that they had a lot in common because they were both mistreated under this oppressive regime.

You’ve touched on so many fascinating aspects that are influenced by piracy, and how piracy can reveal so much about global history to us. So what are some of the key questions and debates in the field of piracy? What are historians of piracy arguing, debating and talking about?

The great problem with piracy has always been that the pirates themselves don’t tend to leave their own written accounts. It’s only very rare that you actually get a first-person narrative from a pirate, which is why contemporary pirates who are alive today offer this great and unique opportunity for studying the phenomenon.

There are not so many historians who focus on pirates. But probably a lot of our debates are similar to those in other fields of history. We ask questions like: how reliable are our sources? And how have the narratives constructed around these sources changed over time? Do they need to be changed again now? That kind of stuff.

Even right back in the mid-17th century, when printed pirate narratives started to emerge, publishers really liked to put a patriotic and romantic spin on what the pirates were doing. And from the 1920s, piracy started to emerge as a field of academic study, most notably by Philip Gosse, and Basil Lubbock, both of whom took a lot of the accounts of piracy from the past and bundled them up into books.

Basil Lubbock in particular was really not inclined to support his findings with actual evidence or references. And when you do start to trace where his sources come from, you discover that he got them from an old storybook! But because the works of Lubbock and Gosse have been around for 100 years now, and there is a dearth of alternate narratives, they’ve effectively come to be viewed sometimes as primary sources. So you’ve got to be very careful about the validity of the first historian’s information. Because of course, it all goes back to these manipulated narratives from the past and the heroic narratives and the patriotism – that’s all wrapped up in it. In a lot of the literature, the pirate is the centre of this adventure story, and the production of these stories became a whole industry in its own right.

Pirates also offer this very strong commercialisation element, because of the public fascination with them. For a lot of people, they sit in the realm of vampires, zombies and ghosts. People don’t actually realise that they’re real people! And that they’re still around – you know, just last week, pirates in Indonesia hijacked a ship. So it’s still happening. But because it doesn’t affect us on a day-to-day basis, pirates have shifted into our subconscious and become these archetypal heroic figures.

And so the challenge is, well, how do you get to the truth? And are you just never going to find the answers for some things? In the last ten years or so, a few historians have really started to pick apart those Caribbean stories from Captain Charles Johnson, an eighteenth-century British author who’s a major source on Caribbean piracy. And they’ve basically come to the conclusion that you really can’t read his stories without verifying the information. It’s just not that reliable. But, it inspired Treasure Island, it inspired Peter Pan, it’s inspired the Pirates of the Caribbean film franchise. All of this can be traced back to this Captain Johnson. There’s a dichotomy between the way the public perceives pirates and how they’re presented in popular culture, on the one hand, and the historical and contemporary reality of pirates and piracy, on the other. I think at this point, you just have to accept that that’s just the way it is.

So I love that idea – that dealing with the history of something so iconic means that you’ve got these parallel streams: working out the history of piracy itself, but also the history of people being enchanted by the idea of piracy for hundreds of years. It’s fascinating how these streams intersect so clearly in the historiography as well, as you seem to suggest.

Thank you so much for sharing so many ideas about the long span of the history of piracy and its continuation in the present.

Great, thank you so much for having me. I’ve really enjoyed it.

Sarah Craze’s forthcoming book Atlantic Piracy in the Early 19th Century: The Attack on the Morning Star is due out later in 2021. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahCraze and via her blog, History of Somali Piracy.

Recommended Reading on Piracy:

- Earle, Peter, The Pirate Wars (Methuen Publishing, 2003).

- Gibbs, Joseph, On the Account: Piracy and the Americas, 1766–1835 (Sussex Academic Press, 2012).

- Head, David, Privateers of the Americas: Spanish American Privateering from the United States in the Early Republic (University of Georgia Press, 2015).

- Little, Benerson, Pirate Hunting: The Fight against Pirates, Privateers and Sea Raiders from Antiquity to the Present (Potomac Books, Inc, 2010).

- Murray, Dian H, Pirates of the South China Coast (Stanford University Press, 1987).

- Pennell, Richard, Bandits at Sea: A Pirates Reader (New York University Press, 2001).

- Van Ginkel, Bibi and van der Putten, Frans-Paul, The International Response to Somali Piracy (Brill, 2010),

- Young, Adam J., Contemporary Maritime Piracy in Southeast Asia: History, Causes and Remedies (ISEAS Publishing, 2007)

Journal articles

- Bialuschewski, Arne, ‘Pirates, Markets and Imperial Authority: Economic Aspects of Maritime Depredations in the Atlantic World, 1716-1726., Global Crime 9, no. 1-2 (2008): 52–65.

- Craze, Sarah, and Richard Pennell, ‘The Pirates of the Defensor De Pedro (1828-30) and the Sanitisation of a Pirate Legend,’ International Journal of Maritime History 32, no. 4 (2020): 823–47.

- Durrill, Wayne K., ‘Atrocious Misery: The African Origins of Famine in Northern Somalia, 1839-1884.’ American Historical Review 91, no. 2 (1986): 287–307 (on shipwreck raiding in Somalia).

Online resources

- Davies, Dave, Surviving A Somali Pirate Attack On The High Seas. NPR, 6 April 2010 (interview with Captain Richard Phillips of the Maersk Alabama).

- Palotta, Tommy, and Femke Wolting, Last Hijack Interactive, Submarine Channel (2014) (online documentary providing multiple perspectives on Somali piracy).

- Vallar, Cindy. Pirates and Privateers (excellent historical investigations into pirates and pirate book reviews).