Editing the Adams Family Papers: An Interview with Sara Martin

After completing her PhD in History at the University of Melbourne, Sara Martin went on to pursue a career in Public History and is currently Editor in Chief of the Adams Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston. In a conversation with History PhD candidate Jonathan Tehusijarana, Sara shared her reflections on the importance of Public History, and her advice for History graduates looking to enter the field.

Sara, you completed your Masters in Arizona before moving to do your PhD in Melbourne. What prompted you to make this decision? And are there any major differences between studying in Australia and the United States?

I had an advisor at Arizona State University who was well-connected with the public history communities in Australia and New Zealand. She heard about the central Victorian goldfields project that Alan Mayne and Charles Fahey were working on and brought it to my attention. It touched on so many of my research interests that it was really enticing. I remember writing to Charles to ask if they would even consider a foreign applicant. Fortunately, the answer was yes!

The length of the Australian program also appealed to me – three to four years versus the average six to eight in the United States. That difference results from the requisite with most US programs for coursework and reading comprehensive exams, which take at least two to three years in addition to your research and a book-length thesis. There are many benefits to the system, namely that it produces historians with deep knowledge in multiple subject fields. For most, it also comes with a significant financial commitment or other challenges. I felt that my master’s program provided the foundation I needed to embrace the more self-directed approach in Australia. I was able to continue to tap into my US network for advice and counsel and I had great Australian advisors in Charles Fahey, David Goodman and Alan Mayne to help guide my reading and research.

For your PhD in Melbourne, you examined the lives of families in the Victorian goldfields. Why did this topic pique your interest? Was it related to your Master’s thesis?

Family migration was the focus of my Master’s thesis. There, I specifically looked at emigrants [to California] along the Overland Trails. I edited the diaries of a sister- and brother-in-law who emigrated as part of a large family group, not to the western US goldfields but to agricultural lands in Northern California in the 1860s. The goldfields, however, are deeply engrained in that story. So, the focus for my PhD built on shared histories, albeit with a new geographic focus. The ways individuals and families situate themselves in larger historical narratives is fascinating to me, and I was able to continue that work in Melbourne.

You went on to become Editor in Chief of the Adams Papers in Boston – a major publishing project centred on the papers of the family and descendants of John Adams (1735–1826), the second President of the United States. His eldest son, John Quincy Adams (1767–1848), was the sixth President and also served as Secretary of State under President James Monroe, helping to author the Monroe Doctrine, a foreign policy doctrine that still influences the United States’ relations with its North and South American neighbours.

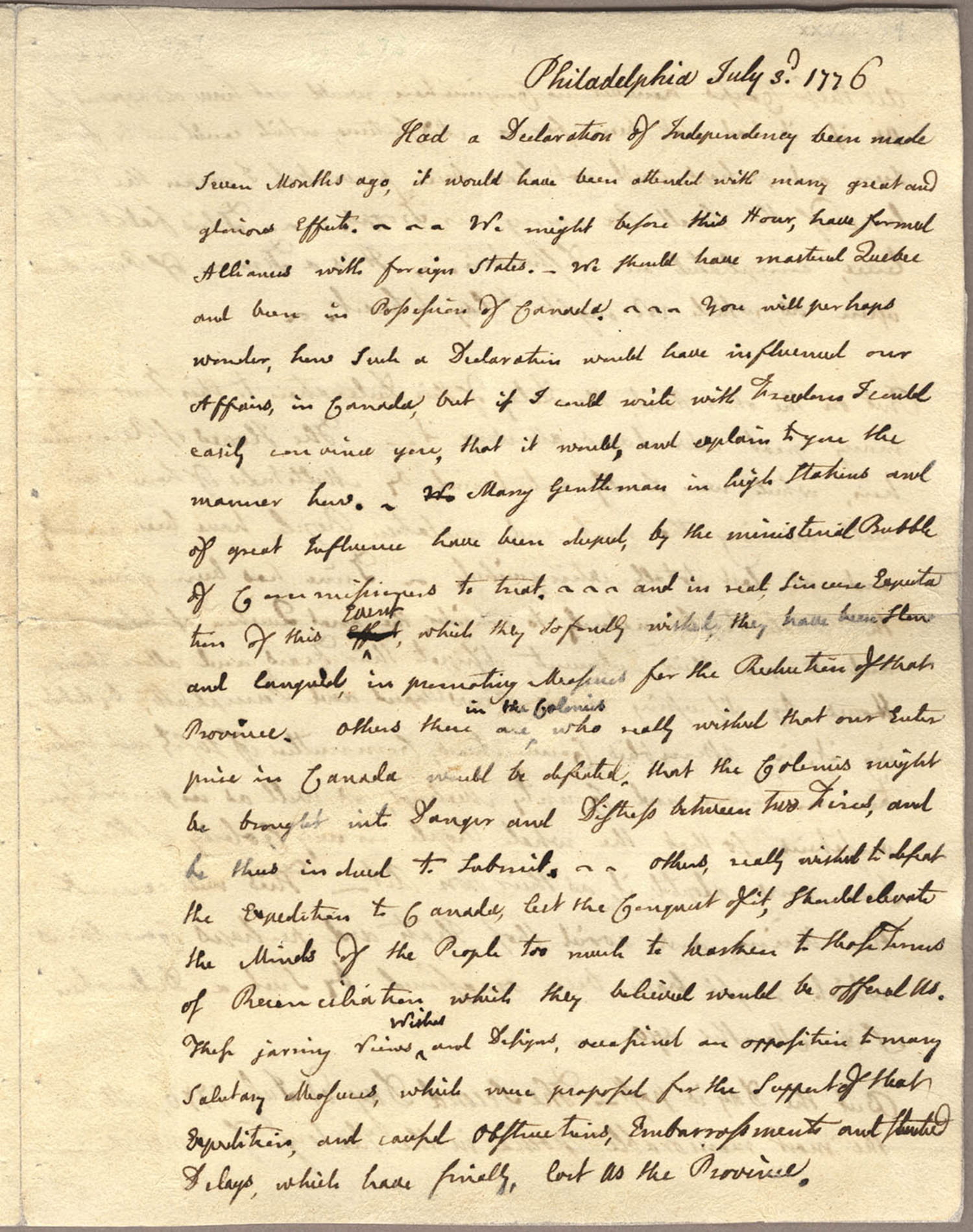

The collected writings of the Adams family include a large amount of personal correspondence, diaries and other manuscripts produced by three generations of the family. These documents provide unprecedented insight into American life throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The Adams Family Editorial Project began in 1954 after the Adams family donated its papers to the Massachusetts Historical Society. That collection – the Adams Family Papers – forms the project’s core, although the project also considers for publication Adams documents held by other institutions and individuals. The Adams Papers Digital Edition provides online access to digitised versions of previously printed volumes of the papers, and the project is currently working on their first born-digital edition, the John Quincy Adams Digital Diary.

How did you end up working on the Adams Papers project?

Historical documentary editing – the accurate transcription, contextualisation, and publication of historical writings – was the focus of my master’s thesis. In truth, I arrived in Victoria with hopes of finding a similar group of documents from which to explore Anglo-European goldfields settlement as part of my doctoral work. The sources did not play out that way. Instead, I relied on a selection of material traces to tell that story.

When I returned to the United States, I knew I wanted to continue my work in the public history sector. The position with the Adams Papers allowed me to return to the historical editing I’d previously enjoyed.

Could you briefly describe the kind of work you do at the Adams Papers?

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston publishes a comprehensive edition of the collected writings of John and Abigail Adams and their descendants. The family’s papers span more than 150 years and provide the family’s view of public events and domestic life from the mid-eighteenth century through to the end of the nineteenth century. They are a key resource for the study of American history, society, and culture.

As the editor in chief of the Adams Papers, I oversee the publication of two letterpress and two digital editions. I remain engaged in the work of an editor and historian and lead a team of editors in the selection and contextualisation of documents for publication and production of print or electronic volumes. I am also an administrator, a grant writer and fundraiser, and an advocate for history in the community through a host of public engagement activities that range from in-house exhibits to multi-institution collaborations. Every day is a little bit different and I love that challenge. It is truly rewarding to be immersed in the amazing body of writings produced by the Adams family, to make those writings more accessible to the public and to advance historical understanding.

One of my fellow postgraduate researchers Luke Yin reflected in a recent article that historians were especially well-placed to provide the kind of long-term thinking demanded by the COVID-19 pandemic and other global challenges that we currently face. He argued that historical thinking and historical knowledge can help humanity cope with change, including the catastrophic and profound changes that pandemics bring. Public history is one way of disseminating and popularising scholarship about the past and highlighting the public value of historical research. Your studies and your work with the Adams Papers have all dealt with public history in one way or another. Why do you think that this field is particularly important today?

Events over the last year have shown how deeply engrained our past is with the present. The practice of history is vital to identifying and critically examining those connections. Public history helps do that for broad audiences. It builds collaborative spaces where the intersections between the past and lived experiences today can be analysed. The best public history evolves with the changing times and amplifies community voices in telling their stories. For a project like the Adams Papers, the depth and breadth of content invites scrutiny beyond the traditional narratives of the founding era. The wealth of detail informs social and cultural history and can be mined by researchers in a host of disciplines.

Academia has long been accused of being self-interested and catering too much to a specialist audience. Do you agree with this charge? How do you think postgrads and early career researchers could make their work more relevant and engaging to the general public?

I would love to see more history and humanities departments include professional skills training as part of their postgraduate programs. There is a need for this training even within the academy but it is increasingly useful as graduates find employment outside of it.

Different approaches and outcomes are necessary for different kinds of history production. The writing you engage in for a thesis or scholarly monograph is quite different than that needed to produce a blog, or op-ed, or to draft a cultural heritage report (or even a department memo). Presenting a conference paper is different to introducing a general audience to a historical topic. All build from the strong foundation in research and analysis that you develop in postgraduate programs, but learning to be nimble in the delivery of historical information is not always something that is emphasised in programs. It can challenge graduates or early career professionals who are entrenched in one model of production. These skillsets should be fostered and taught at the institutional level, but they take time and practice to perfect.

The phrase ‘alternative academia’ has been widely used to encourage postgrads to look for jobs outside of traditional academy. Working in an ‘alt-ac’ position yourself, do you have any thoughts on this? What advice would you give postgrads considering a career path like your own?

People earning PhDs have worked incredibly hard to achieve their level of expertise. The state of the academy means that more postgrads are finishing their doctorates than the academy can support. That is a frustrating reality. Unfortunately, the fact that you’ve completed a postgraduate degree with a focus on scholarship and teaching may not necessarily open doors into fields that have their own methodologies and training requirements.

If you seek a position outside the academy, you need to do your research. Figure out where and how your skills transfer, where your deficiencies are and ways you can bridge those gaps. Do the legwork, find a mentor, engage with a relevant professional organisation and, most importantly, recognise that alt-ac work shouldn’t be seen (or at least presented) as a fallback. It may not be the path you originally envisioned but it can be equally as rewarding and lead to vitally important contributions to the field and society as a whole.

With luck, more postgraduate programs will offer professional training beyond teaching. In the meantime, students may best be served by approaching their postgraduate experience with a bigger picture in mind.