Why Study Ancient Languages? An Interview with Dr Edward Jeremiah and Dr Andrew Turner

We are excited to announce the appointment of Dr Edward Jeremiah and Dr Andrew Turner as Teaching Specialists in ancient languages. Andrew and Edward play key roles in introducing our students to Latin and Ancient Greek, and guiding them through their journey as they learn to read classical texts in the original language. In addition to being highly experienced and committed educators, Andrew and Edward are both also accomplished scholars with deep expertise in their respective fields, and valued colleagues in the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies. To celebrate their appointments, we are featuring their teaching and research in this interview, conducted by PhD candidate in Classics Ash Finn, who sat down with Andrew and Edward to discuss how classical languages are taught at Melbourne, and why classical languages continue to be relevant in our modern world.

Transcript

Ash

Hello, and welcome! I’m here with Edward Jeremiah and Andrew Turner, two of our Teaching Specialists in the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies. They both specialise in ancient languages, Greek and Latin. And we’re going to find out a little bit more about what they do, and what teaching they do here in the School.

You’re both teaching here. Could you tell me a little bit about what you’re teaching, and some of the elements that you’ve chosen for your subjects, and why you’ve chosen them?

Ed

So, Ash, I’m taking the beginner subjects for Greek and Latin. So I’m teaching, currently, Latin 1 (CLAS 10006) and Latin 2 (CLAS 10007), which are taken by people who’ve had no exposure to the language. And if you do Latin 1, and then Latin 2, that will take you a year of study, so two units each.

We really cover the basics of Latin grammar, and prepare you for the subjects that Andrew has been teaching for the last few years, which is to engage with your first Latin text. Because it takes a while to just build up all the grammatical toolkit and the linguistic toolkit to be able to read a full text. And that’s what my two subjects in Latin are building, educating the student to be able to do.

And similarly with Greek – I’m also teaching the beginners’ level subjects there at the moment. So yeah, Greek 1 (CLAS 10004) – that’s for your students who’ve had no previous exposure. We start right at the beginning with learning the alphabet on the first day.

And then if you take Greek 1 and Greek 2 (CLAS 10005) – a regular plan would be a year’s worth of study – that builds you up to be able to be engaged and read a Greek text in your second year of study.

I’m using textbooks for both of those. Because Greek and Latin have been taught for so long, there’s a bit of politics around which textbooks are the best. I’ve taught with different textbooks and they all have their pros and cons. I use the textbooks as a grounding, but then I introduce a lot of my own material around that. Textbooks can get a bit boring after a while, so I try to bring in other materials to supplement that.

Ash

Thanks for that, Ed. And for you, Andrew?

Andrew

Some of my courses actually build on Ed’s courses, and we get a lot of great students coming out of them.

This semester I’ve been teaching Latin 3 (CLAS 10012), which is really the point where you first encounter a major Latin text. It’s usually Cicero’s Pro Caelio, which is a very vivid speech, in defence of a rather dubious character. It’s got some brilliant pieces of Latin in there but it is really hard.

What we do at that level is we amalgamate the students who’ve come in from Ed’s teaching, which is the students who’ve done either beginners or intensive Latin courses with Ed at the university. And also we’ve got the students coming in as first year students from VCE. So we’ve got a mixture of second and first year students.

One of the aims of that particular level is to make the students homogenous because they’re coming from using different methods. Each school seems to have its own method of teaching and so on. Ed uses a great standard text which teaches them so much grammar, but at the same time, students’ knowledge is all over the place. So one of my aims in terms of the teaching, the pedagogy, is to make the students homogenous in how they tackle grammar and so on.

The way that we do that is we use a grammar course, which is a grammar book of new Latin syntax by E.C. Woodcock, it’s called New Latin Syntax – it comes from 1959 but it’s still relatively new with regard to a lot of Latin. And so side by side we have the grammar lessons and also the textual lessons and Cicero. That’s the Latin 3 course.

And then it goes on to Latin 4 (CLAS 10014) – Tim Parkin’s taking it, this year, but I’ll still continue doing the grammar classes from Woodcock.

And then this semester I’ve been teaching Latin 5 (CLAS 30013) and I’ve done Petronius’s Cena Trimlachionis, which is part of his Satyrica which is one of the funniest and bawdiest Latin novels that’s in existence – one of the two in existence, actually. So that’s a little hyperbole there! But in any case, it’s an extremely amusing text.

Ed

Can I just jump in there? I was showing my students the Wikipedia page of the plot outline – to give them a taste of how ridiculous and fantastical the whole thing was, and they loved that.

Andrew

Yeah, it is a terrific text to teach. All the students said to me afterwards that that was such a fun course.

And I do Horace’s Odes in Latin 6 (CLAS 30009), which will be next semester. So it’s a broad range of literary texts.

When you get to this to this level, to the 5 and 6 level, you don’t do any more direct interface with grammar, but you have to have recourse to grammars and you have to have recourse to dictionaries. So what I’m trying to do at that level is teach students how to do things for themselves, how to use online resources. I’m trying to build in at this stage using online dictionaries and online search databases in order that they can expand their particular knowledge and usage of Latin at the same time.

And hopefully, these sort of things, at this level, a lot of our students – what would you say, Ed, maybe 50% of them – would be doing both Latin and Greek consecutively or concurrently. So a lot of the teaching sort of leaches over from one course into another. We’re quite happy with that cross-fertilisation.

Ash

Thanks, Andrew! You talked a little bit there about using the internet and online resources, and I’m wondering, during the past year, how both of you coped with online distance learning? And what do you both think the future is for online distance learning in the study of ancient languages?

Ed

The real point where I think the benefit of direct face-to-face teaching takes over is in the sense of human community. And that’s really hard to replicate, especially among students, that sense of kind of collegiality, you know, often because of the courses …

One of the good things about ancient languages is that they tend to be quite small classes, which means that you can have more of a personal relationship with your students – they’re not just one in a number. Some of these big courses have hundreds and hundreds of students so you can get kind of lost in the crowd, so to speak. So I can have more of a direct relationship with the students and the students themselves get to know one another. And often they just naturally form a kind of study community in their own time, and they go out for drinks, and they socialise outside of class, and they share their passion for ancient languages. And that kind of energises, you know, you get this mutual energisation, where they’re each encouraging one another. And that’s great to see. And that was certainly lacking, I think, when we were teaching everything purely online.

And with the shift back to face-to-face teaching – so both my classes, my Latin and Greek class, I taught in person fully in-person this semester. And yeah, I could just see from the students, and especially forming those social bonds that they were happy to be back and they loved it.

Andrew

I also noticed in my own class, that the students this year, in particular, coming back from the lockdown, tend to be far more sociable, that they were making groups within class. It was quite obvious, which I haven’t really noticed in the past before, but this year, it was really marked.

Ed

Yeah, well, I couldn’t believe it, my students had set up, like, you know, they had a whole Facebook Messenger group going, and it’s basically the whole class was in it. You know, after every class, they were going off to get coffees or have lunch or whatever. And they performed really well too, in their study, which is telling me that, you know, it’s a virtuous circle – if they’re talking about Greek and Latin in their social time, and memeing about it and joking about it, it can only be good for their studies.

Ash

You’re both working in teaching, but you both also carry out your own research projects.

Could you tell me a little bit about those research projects and how they relate to the teaching you do here?

Ed

Yeah, thanks, Ash. So my main research that I’m doing at the moment is on helping to translate a text by a gentleman called Cyril of Alexandria. It’s a text from the fifth century AD. It falls within the genre of what’s sometimes called Christian apologetics, which is where Christians are defending the rationality of their faith and the rationality of theology against attacks from pagan intellectuals.

This particular text that I’m translating is called Against Julian. And it’s a text that was written against the apostate Emperor, Julian, who was a neo-Platonist. And he wrote a kind of polemical tract called Against the Galileans. ‘Galileans’ is basically his term for Christians. And of course, after him writing that text, tearing apart Christianity, arguing how silly it was, how irrational it was, how inferior it was to pagan philosophy – that motivated all the Christian philosophers to come out and defend Christianity.

So, I’ve been working with some colleagues at ACU and overseas on translating that text – it hasn’t been translated into English before. So yeah, that’s been taking up a lot of my research time.

I actually brought in a section of the text, in probably the first week of my Greek class, just so we could practise reading some things aloud. Of course, they had no idea what it meant – we’d learned the alphabet. So you know, here’s something that I’ve been doing recently. And, you know, even though we’ve only had a few classes together, we can kind of still engage with some of it, we can start getting our mouths around some of these Greek foreign sounds.

And whenever I’ve got a difficult passage that I’m working on translating, if they’re up to it, sometimes I bring that in and talk about some of the difficulties I’ve been having. Because I think students enjoy getting a taste of what it is that we actually do, you know, in our research, like: what is it that you do when you’re not teaching us? I think that students are often quite curious about that. So yeah, that’s my main kind of research project at the moment.

Ash

Thanks, Ed. And yourself, Andrew?

Andrew

I work mostly on Latin texts all the time. And it’s basically on the reception of classical Latin literature in the Middle Ages. I’ve worked on Classical Studies, classical texts in the Low Countries. I had a project where I was in Belgium for a while. And I’ve also worked extensively on Terence with my colleague Giulia at UNE.

At the moment, I’m working with our colleague K.O. Chong-Gossard and Professor Bernard Muir on a project on the reception of Seneca. In the early 1300s, an English monk called Nicholas Trivet wrote a commentary on the plays of Seneca. It’s the first full commentary that was in existence and it hasn’t been translated, and only been poorly published. And so we’re actually working on the text of that, and trying to work out how people read classical texts at a later period.

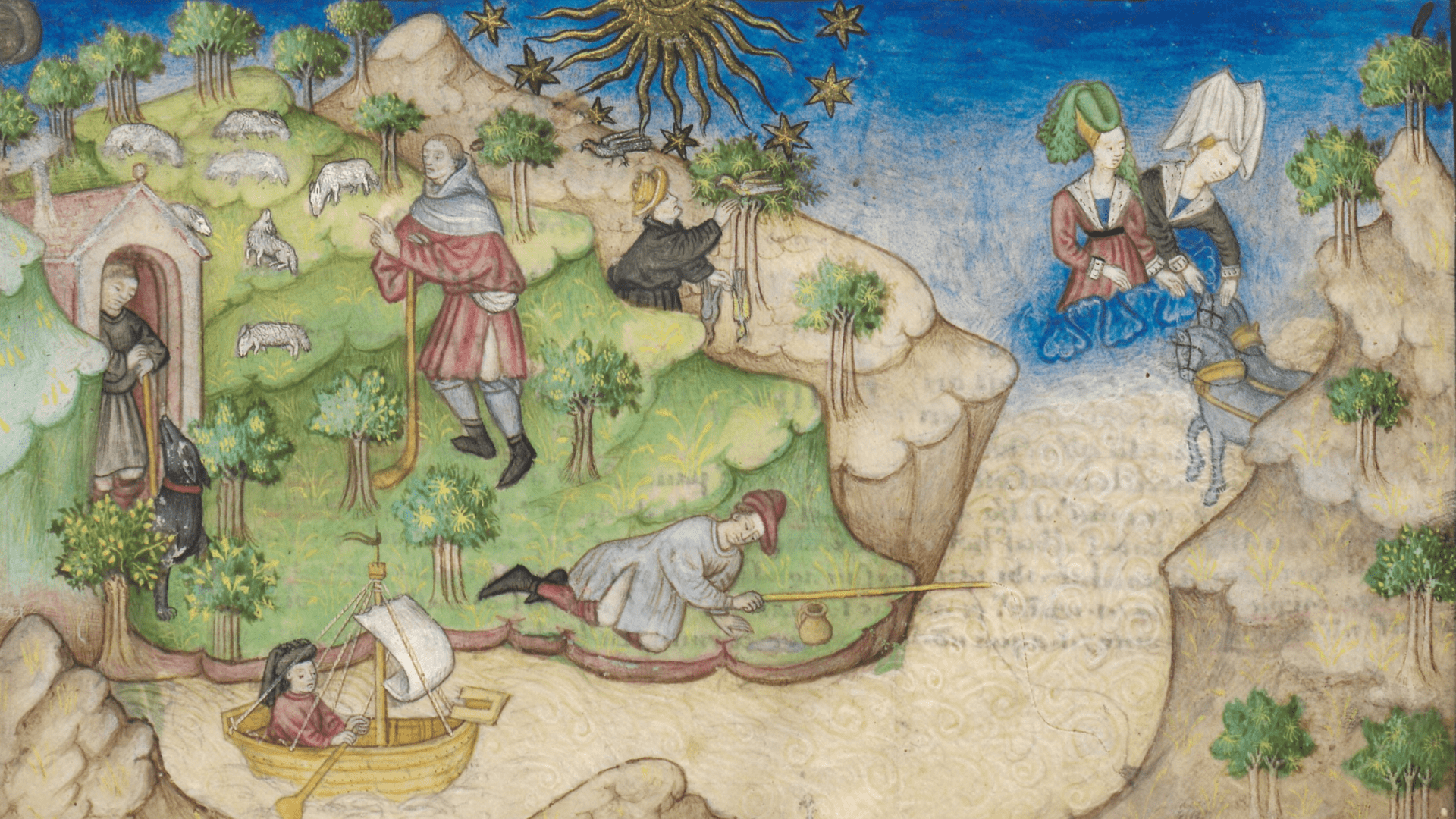

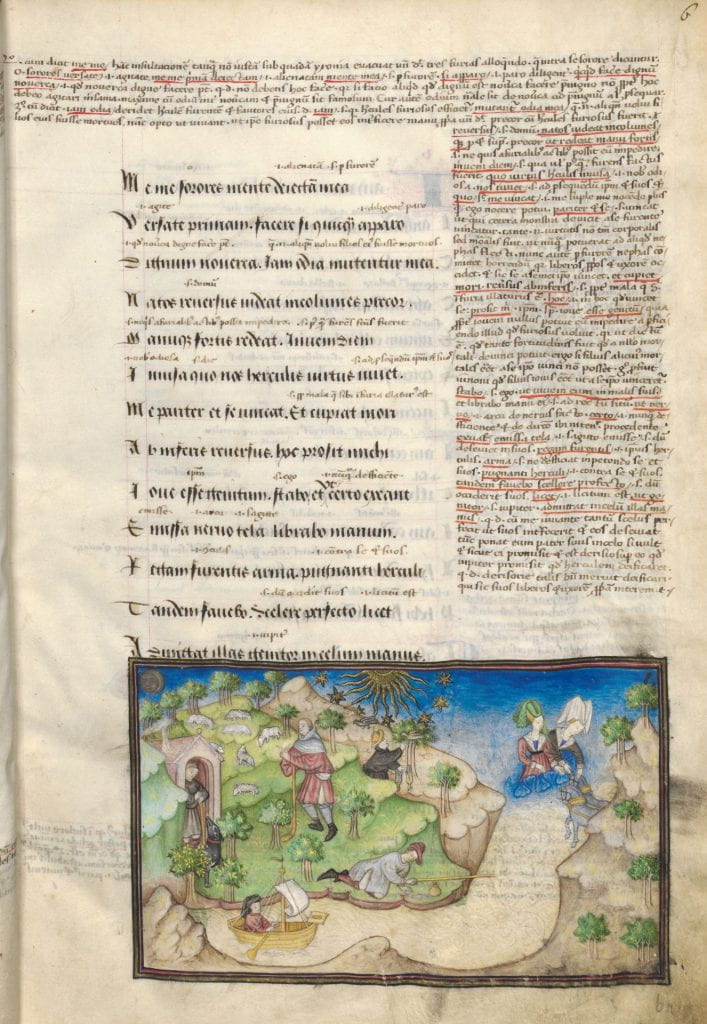

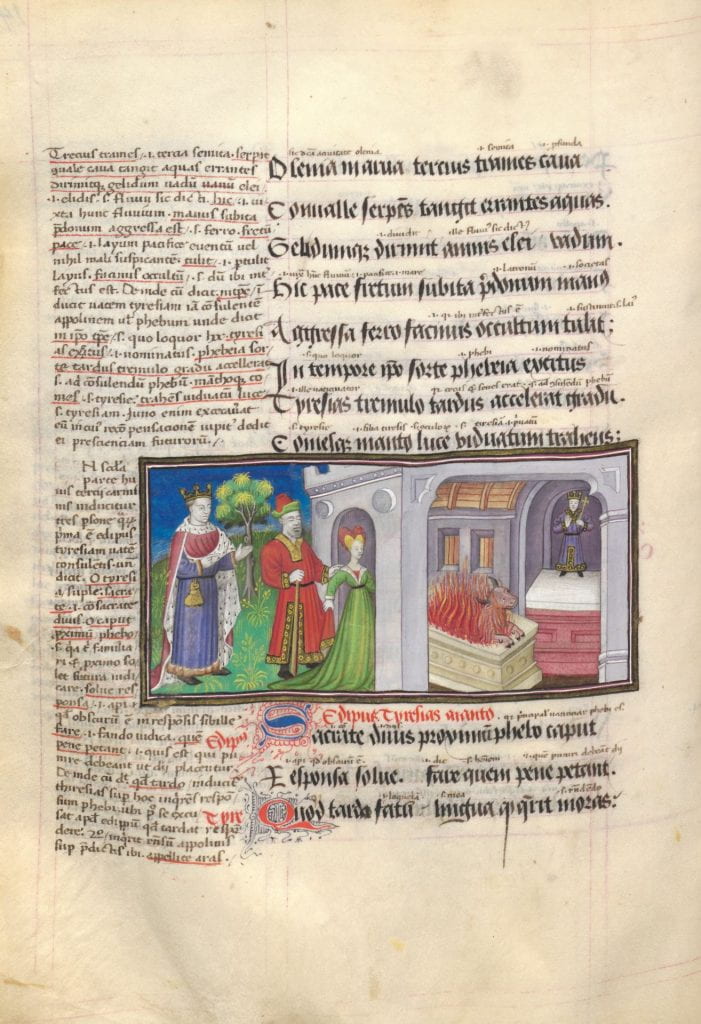

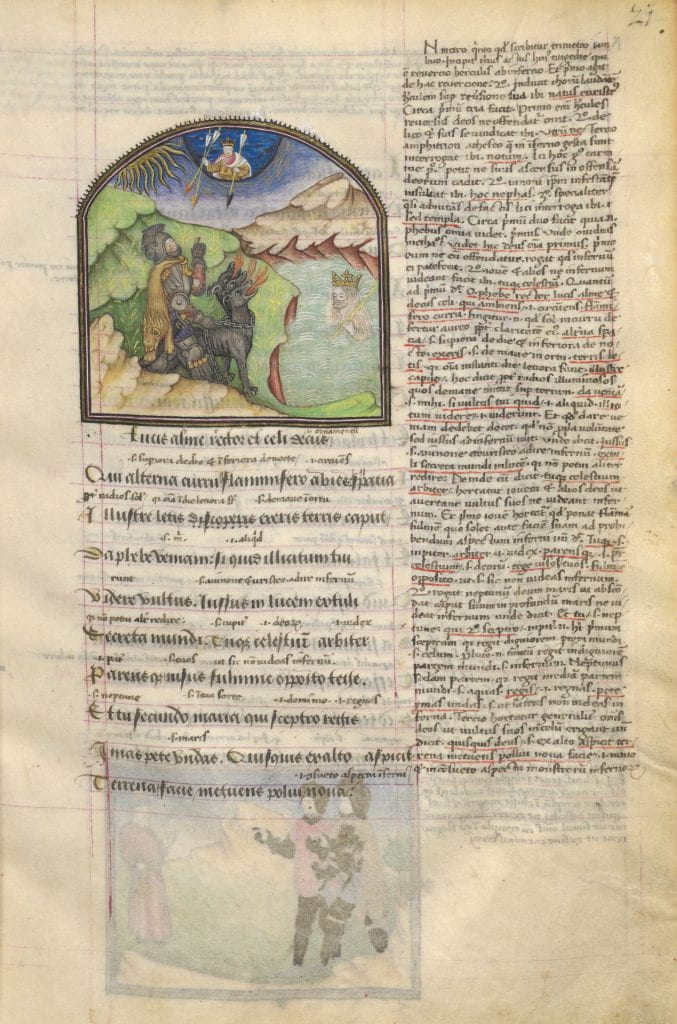

And so it’s really rewarding. I deal very extensively with manuscripts and early printed editions – I’m just going to bring up a screenshot of the sort of stuff that I deal with quite a bit …

So this shows a manuscript, it’s from around the year 1420 – an illustrated manuscript of the plays of Seneca. And you’ll see that there’s a couple of elements in there – apart from the illustrations, which are gorgeous in this particular manuscript – but you can see there’s a main text there, but on the side, there’s what’s called scholia, which is commentary. And that’s actually what we’re dealing with, the scholia in the commentary – it’s also written between the lines in the manuscript.

It can be boring, I mean, in terms of the contents of the commentary, because it’s just simply trying to explain to an audience, to contemporary readers, what Seneca meant in the period. Also, it’s got a lot of anachronisms in there. He’s talking from the point of view of the 14th century, so sometimes he doesn’t know stuff, and so he has to make it up and give an explanation of what a particular passage means. And some of them are quite funny mistakes.

But in any case, it’s really intensive work – Bernard and I spend many hours together sort of poring over stuff like this. This is actually the nicest manuscript that we work with, so it’s giving you probably a false idea of that.

But I find too, as Ed was saying, that when you talk to students about these sorts of things, and engage with them, and suddenly show them that there’s a world outside of the text that they’re dealing with, and the printed edition that they think is gospel, and in the fact the printed edition comes from somewhere else. It doesn’t actually come from, you know, it’s not the words of Seneca that they’re reading, they’re just reading someone’s interpretation.

Ed

Yeah, I love showing them like an apparatus criticus of a text that I’m dealing with, which shows the whole manuscript tradition behind a chosen reading, that an editor has decided this is the most likely the correct version of the text at this point. And yeah, they often find that fascinating that there’s been this whole editorial processes that’s been gone through to arrive at the text that we just take for granted.

You pick up your Plato in English translation, and you’re like, that’s Plato, that’s what he said! But if you dig a bit deeper, you find that there’s these long and complicated manuscript traditions that are quite rich, and that there have been choices that people have made along the way to arrive at the particular text that we have. … Because it’s all about interpretation, then – that opens up a lot of doors, and thinking about texts as these open-ended things. It’s a great thing to do.

Ash

This brings us on to our next question: in a more modern and global world than perhaps it was 50 or 60 years ago, what role do you think the study of Latin and Greek has, or should have, in the modern world?

Andrew

Well, I mean, we’ve got a vested interest, understandably, because we need students and we have to say, you know, this is why it is! But I think there are some really genuine advances that people haven’t really caught up with. One of them from my point of view is digitisation. The images I showed you – although that particular manuscript isn’t available on the web, you can already get some of the most important manuscripts available just by clicking a few links, if you know where to go, to the Vatican Library website or the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, and Greek and Latin texts, they’ll be available there.

This wasn’t the case previously. You’d have to come to Oxford or Stanford or somewhere like that, to be able to consult manuscripts in situ. But now, suddenly, there’s this sort of wave of material that’s out there that hasn’t fully been accessed and from my own point of view, I think we really need to teach people linguistic skills in order to deal with this and also paleographical skills – that’s a step further – in order to make sense of this digital information, because it is out there. I mean, it is exponential, the rise in the past ten years of the information that’s freely available from these major libraries, the British Library, as I said, the Vatican library is sensational for some of the stuff that it’s got.

From my own point of view, that’s one of the greatest things that we can do is train people to deal with these sorts of texts. If the information’s out there, people are going to say: Well, what does this mean? You know, how do you read it? Why is this different from the text of Homer I’ve got in front of me? Why is it saying this? And so, in order to deal with those sorts of things, you really need to have that linguistic training. So that’s my main idea on that particular topic.

Ash

That’s brilliant – thank you, Andrew. What about you, Ed?

Ed

Okay, let me be a bit philosophical. So there’s this word, cosmopolitan, that’s come into English. And it literally means to be a citizen of the cosmos, of the world. And it really captures the spirit of globalisation. This is a word that was used first – apparently, if we believe the tradition – by a Cynic philosopher, and was later taken over by Stoicism, which was an early school of ancient philosophy, started by the Greeks. And it expresses the idea that one’s first attachment, or one’s primary identification should be with the world or the globe, not with a particular city state, which was a kind of radical idea at the time, because most people, you know, most agents saw their primary affiliations with a particular city state, and with structures underneath that, like one’s family, or one’s clan.

It’s really with the Greeks and Romans that we see humans struggling to form an idea of human community that does go beyond these political boundaries. So if you want to understand globalisation, you really have to understand where these discourses came from.

And another thing on the philosophical roots of globalisation: if you look at the main thinkers of modernity, especially in the West, and you look at who they were reading, and who are they writing their theses on; if you look at, you know, who the founders of the American Republic were reading, when they were drafting their various codes, it generally comes back to the Greeks and the Romans.

And again, there’s another strong argument that, you know, you look at, say, Imperial Rome, that a lot of the forces, there were kind of mini forces of globalisation in effect there, too. And they were also facing similar problems that we have today, like, how do you settle claims of justice between, you know, warring nations or claims of justice between warring empires?

It’s again in that period, that you see embryonic notions of things like human rights – again, a lot of it’s backed by the philosophical school of Stoicism. If there’s a kind of a universal brotherhood of humanity, are there certain rights and obligations that come with that? And do those rights and obligations kind of trump or are they more important than local norms, local rules, local laws, etc.?

So, you know, the Greco-Roman world, and the wider ancient world more generally, was quite globalised already. There were quite vast trading routes. Empires rose and fell. And they went through periods, more open liberal periods where there was more trading, more interaction. And then they would have anti-global movements too, where there was a kind of retraction, and we’re seeing these same forces in play today.

So, yeah, I’m a real believer in the idea that if you want to understand populism, study the late days of the Roman Republic! There are so many lessons to be learned from that for understanding populism in our own period. If you want to understand conflicts between rival powers, you know, there’s a lot made these days of conflicts between, say, China and America – well, there are similar kinds of conflicts between great powers in the ancient world too. They can provide a kind of model or mode of understanding what’s going on today. A lot of this stuff we’ve seen before.

So, basically, to sum up this philosophical point of view: if you want to understand the modern world, I think you really do need to understand the classics. A lot of what seems to be new is not so new. And even when it is new … the other thing is that there’s weird thing that’s happened too in human history, where looking back to the past is often associated with periods of great renewal and rejuvenation. If you look at the effect of the Renaissance, for instance – and there’s been lots of renaissances in human history. And it’s this weird thing where human creativity can stagnate for a while, and bizarrely, by looking back and re-engaging with the past, and reading the past, again, deeply, it just leads to a flowering of new ideas. So yeah, I mean, I think we need another Renaissance, to be frank! That’s not going to happen unless we start reading the classics deeply again.

Ash

If you were talking to a young school student today, who was thinking about studying ancient languages, what would you say to them?

Ed

I would say: if you want to broaden your understanding of human history and the human story; if you want to read interesting ideas and engage with interesting literature, in a foreign culture, across vast stretches of space and time, in their own language, so entering into their own heads, there’s no better way of doing it, than studying a classical language. And at bottom, that’s really the heart of the humanistic condition – interest in humanism is just understanding what humans were up to, and what they do, and the sorts of thoughts and ideas that they were having, in different cultures, in different times. And it’s just a great way of getting people out of the bubble of the present, and connecting to something that’s broader than themselves. And giving them a totally new perspective on things too.

One of the things that I think students of classical languages get, is they get this renewed appreciation for their own language and for language in general. Because it really, especially when you get onto the high levels, like what Andrew is teaching in Latin – engaging with the text really means engaging with each sentence, you know, what exactly does this word mean in this particular context? So it really gives you a detailed appreciation, and sensitivity to what language is doing at the deepest level. And they can take that approach then to the way they write their essays.

Basically what I’m saying is, they’ll never look at a text the same way again. Once you’ve read an ancient text deeply, you’ll read newspapers in the same way, with a real deep concern for interpretation and how language does what it does.

Also you’re going to always get a bit of old vocab., too. Let’s be honest, if you study a lot of classical languages, your English vocab. will balloon. And you can certainly show off in your essays with all sorts of new Latin and Greek technical terms that you’ve learnt.

Ash

Thank you, Ed; and for yourself, Andrew?

Andrew

Yeah, I’d echo a lot of those sentiments. You have to be realistic about this and say to them, Well, look, initially it’s going to be hard. It’s going to stay hard all the time that you’re learning it. And I know most schools – I think there’s only about two schools in Victoria that actually teach Ancient Greek and maybe about 20 or so that teach Latin – but at the same time, it’s a hardness which is really rewarded with what you’re doing. It’s not pointless.

There is a concision in Latin and Greek which is not in our modern-day languages. We tend to talk about, like, I see all the time articles about hyperbole, a Greek term which means throwing over or throwing beyond, which is just saying that everything’s ‘awesome’ or ‘amazing’, or whatever, in language. And that sort of seeps into everyday speech – because someone says it on TV, people keep on repeating those sorts of ideas. But the great thing about classical languages is that they’re really pared down – you can say something in six words, which takes 20 words in English, and has more depth and meaning to it.

Once you learn those hard bits – and there’s a lot of memorisation – but at the same time, you start to get so much more out of that compact information, then you will out of streams and streams of information coming from, you know, a video or from, you know, some social media or something like that. And it’s a real skill.

So I would advise any students who have the opportunity at schools – and I know a lot of schools don’t teach it, so you have to make a special effort, special schools or whatever – but Victorian College of Languages, I think… But in any case, it really, really does repay you. So if you do get the opportunity in school, I would say go ahead and do it, because you don’t know exactly where it’s going to lead you, but it’s going to lead you to a much more advanced level in a far quicker time than you realise.

Ash

Thank you for that, guys! And one final question I want to add on there: if you were stuck on a desert island, and could only take one ancient text with you, which one would you take?

Ed

You sprung this on us! I don’t think you included this in the questions that you sent us.

Andrew

I’m just thinking, would I take Petronius? Or would I take Virgil? I think I’d take Virgil.

Ed

Well, my heart is divided between poetry and philosophy. And it’s really hard … This is a question that’s forcing me to choose one or the other. So it would be, you know, on the day that the poet in me is ruling the day, it’d be Homer. But on the day of the philosopher, I don’t think you could go past the Platonic Dialogues and especially the Republic. I mean, that’s a kind of cliché, but it really does contain multitudes. And yeah, I couldn’t go past either one of those. So I’d try to smuggle the second one on there as well.

Ash

Great! Thank you for your time, gentlemen! And thank you for your very interesting answers to the questions.

Andrew Turner has decades of experience teaching intermediate- and advanced-level Latin at the University of Melbourne, and has taught hundreds of students the joys of reading Cicero, Ovid, Petronius, Horace, and Propertius in the original language. He is also an expert on the medieval manuscript tradition of Latin literature. Over the past 15 years he has been involved in four ARC Discovery Projects at the University of Melbourne that have looked at Roman texts, including one on a late-15th-century illustrated printed edition of the plays of Terence, for which he was a Chief Investigator. Andrew has edited 3 books that are the outcomes of these ARC-DP projects (in 2010, 2015, and 2020). Andrew is also the former Treasurer of the Classical Association of Victoria, and is an Honorary Fellow of SHAPS. Andrew completed his PhD in Classics at the University of Melbourne in 2000.

Edward Jeremiah is an alumn of the University of Melbourne and Ormond College. He also completed his PhD at UniMelb (Classics) in 2010, and published his thesis as a monograph in 2012 as The Emergence of Reflexivity in Greek Language and Thought. He has years of experience teaching both Latin and ancient Greek at the University of Melbourne, including the summer Intensive Beginners Latin. His research interests include Greek philosophy, and he was a research assistant for many years to Professor David Runia (former Master of Queen’s College at the University of Melbourne) on a project about the Greek philosopher and ‘doxographer’ Aetius (2nd century CE). Ed is currently working with Matthew Crawford at ACU and Aaron Johnson at Lee University to translate Cyril of Alexandria’sAgainst Julian into English for the first time. Ten books and some additional fragments of the original 5th-century CE Greek text survive. The complete translation with commentary will be published by Oxford University Press.