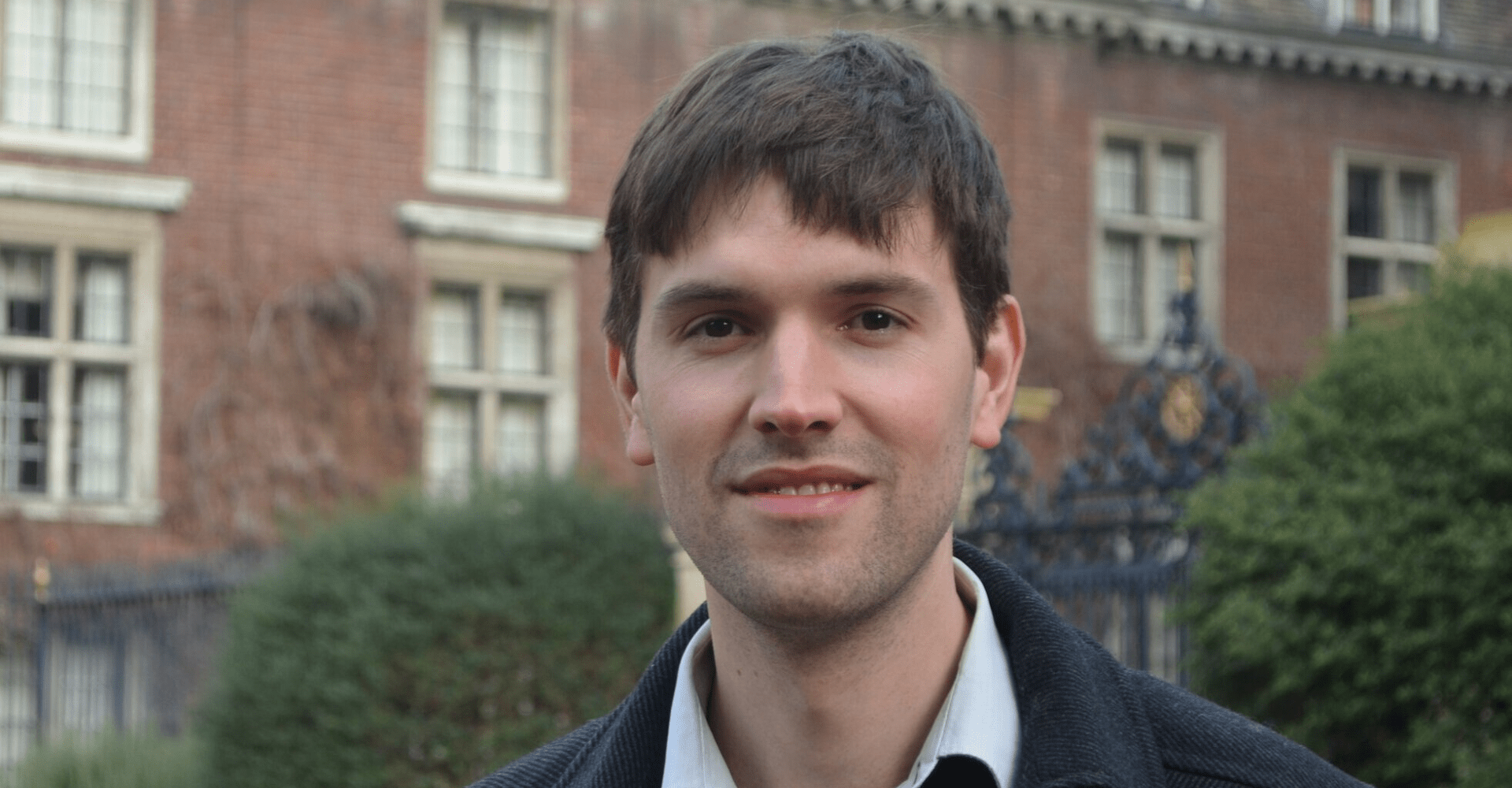

Introducing Dr Matthew Champion

Dr Matthew Champion, appointed to a Senior Lectureship in History in 2022, is a historian of medieval and early modern Europe, with a particular focus on the experience of time and temporality during periods of intense change. In this interview for the SHAPS Forum podcast, Dr Henry Reese talks with Matthew about his research, including his latest project, The Sounds of Time.

Listen on the player below or on your favourite podcast platform. Read the transcript below and scroll through for images.

Transcript

Today, we’ll be getting to know Dr Matthew Champion and his work and taking a journey back several hundreds of years to explore the sounds, material culture, and technologies of time in the medieval world. You can expect a vivid world of singing clocks, sacred hymns and handbills, where the question of who gets to mark the passing of time is hotly contested and tied up with questions of power and agency.

So let’s dive right in. Dr Matthew Champion – welcome to the SHAPS Forum Podcast.

It’s lovely to be here.

Firstly, can you tell us a little bit about your research journey? How did you get to where you are now?

I started off as an undergraduate historian at Melbourne back in the early 2000s. And, there, I was really inspired by some wonderful Melbourne historians, Charles Zika in particular, and a wonderful Honours seminar on history and ritual, which was part of the reason that I started to get interested in the history of time and temporality.

The other reason was that I was concurrently doing a Music degree. This was back in the good old days when you could do combined degrees and have a genuinely transdisciplinary and deep training.

And, there, I did some work on Augustine and a book by him called De Musica (On Music) [late fourth century CE], which had some very unusual thinking about time, numbers, rhythm, and ratios.

So, having this kind of double exposure to different ways of thinking about time made me think that maybe I should do a little bit of work on time as I moved on in my historical study. One thing led to another, and I ended up thinking about time in some demonological treatises, because I wanted to have Charles as my supervisor.

And I then went on to my doctoral studies in London, working on time and temporality in the fifteenth century, working with a fabulous historian – Miri Rubin – a real inspiration. I suppose, accidentally, I ended up with a happy career, moving from my PhD in London to a postdoc in Cambridge, and then back to a tenured lectureship in London. We made a decision then to return to Australia in 2020 to take up ARC fellowships in Melbourne. And I was very delighted then to be able to join the University of Melbourne in 2022, to bring my projects and work on the history of time and temporality to the department which nurtured and fostered me as an undergraduate.

Oh, there’s a lovely sort of circularity to that, isn’t it? Thanks for giving us a sense of your journey so far. I think it’s always fascinating to hear about the trajectory that different scholars take. I feel like it always makes a little more sense looking backwards.

Well, you never really know what is going to trigger historical imagination. I remember Charles saying at the start of one of the Honours seminars – we were reading Miri Rubin’s Corpus Christi, her astonishing study of the role of the Eucharist in medieval life – and Charles always began the seminars by giving a little introduction to the historians. He said: “Miri Rubin – when she comes into the room, it’s like a whirlwind.” And I was sitting there and I thought, “Oh, that sounds like an interesting person!” So, then, when I was Googling my possible supervisors and Miri’s name came up, I had something that I knew about her – that she was a whirlwind – and that sounded cool. So it was really nice then to email her and get such a positive response. It was because of that little observation in an Honours seminar. So there’s always a possibility for something very small to make a big difference in life.

Oh, that’s amazing.

I often say that to my students that there is a transition from being an undergrad and thinking about works that you’re given or things that you find in your own research, to actually thinking about the people who are doing the research, and starting to understand yourself as part of a community of real people doing the interesting research you might have heard about for so long. And, so, yeah, that rings true for me as well.

Something that I think maybe some non-specialists may not be as fully across, or may be a bit more surprised about, is that time and temporality are quite different things; they might be related, but there’s different intellectual work going on in thinking about the history of temporalities. You’ve made some really important contributions in this field. What’s it about and why is it important?

Well, I try to explain this a little bit by way of an analogy with the history of materiality. So our -alities are added to normal nouns like ‘time’ or ‘matter’, to help us show that there might be some more complicated, (to use a word of the moment) entangled, or folded histories that relate to things which might seem simple to us.

For some historians, you might say, time is a kind of neutral ground on which events and historical processes occur, whereas the historian of temporality says: “well, time is bound up and entangled with the very ways in which things can unfold and occur and shapes the way that they do.” So, if you want to think about, say, our pandemic experience – a lot of people immediately started commenting on the way that their experience of time in the pandemic was really different. They felt lost in time, they weren’t following their new normal rhythms. And we know that rhythm and habituation is a really important part of how we experience and perceive time. So you could say there was a different kind of temporality which emerged during the pandemic.

But, then, time itself was playing out; for example, in the way that people were responding to lockdown rules. So, the longer lockdowns went on, different kinds of affective approaches to lockdown rules emerged, different communities could be formed around different kinds of political allegiances. Time itself was playing a role there.

So, I would say that an older history of time might have talked about, as it were, an objective history of time measurement. The history of precision instruments is a technological history of time. That is, of course, incredibly important and not to be effaced as you write the history of temporalities. But the new history of temporalities, as we’re trying to articulate it, is about affective dispositions, political commitments, the ways that time is both being given to us and being made by us as we participate in processes of historical change.

What are some of the key questions and debates in this field? What’s hot at the moment?

One enduring presence in the history of temporalities, as in fact in many forms of historical practice, is the question of whether or not there is a kind of temporal modernity. Is there some kind of radical shift from the pre-modern to the modern? That’s a legacy bequeathed to us from some very longstanding commitments to time among moderns, among modern historians, where we wish to make ourselves, or purify ourselves from what might seem a timeless, static, unchanging religious past, to enter a kind of precise secularising, technological modernity.

Important figures in this story include early German scholars of the late nineteenth century like Gustav Bilfinger or, famously, Reinhart Koselleck’s work Vergangene Zukunft (Futures Past), where different points in time are made sort-of-ruptures between this old world which we’ve lost and the new world which we inhabit. Different people have different aesthetic and affective and political commitments that attach to those divisions. So some people will mourn the loss of that world, other people will endorse acceleration.

Some of the more inventive and interesting theorists to me sit slightly more on the mourning side: Paul Virilio, on dromology and speed; Hartmut Rosa, the German sociologist (in many ways a follower of Koselleck), sees the increasing social acceleration of modernity as a process of alienation, which is tied up with affective dispositions in relation to anxiety and depression.

That’s one enduring debate which I and others, Stefan Hanß, for example, in Manchester, Alexandra Walsham in Cambridge, are trying to push against – that is to say, there have always been complex, plural and changing times. There are different configurations. So without denying that there’s change and that there may be different forms of modernity, wanting to trouble this idea of a kind of static, timeless, medieval (or sometimes early modern) other – that’s one big debate.

I’d say that there are then two other areas which are particularly hot and they match interests again in other historiographical fields. One is the history of time and globalisation, racialisation, and colonial practices. What happens when different times encounter each other? How do people react to processes of temporal control, to bring us to the theme of the podcast? How do people manage to live sometimes in multiple temporalities in these new environments, and how does that change both the colonised and the coloniser? Really important theoretical interventions have addressed this in the past: Dipesh Chakrabarty’s Provincializing Europe or Johannes Fabian’s Time and the Other. But there’s increasingly really nuanced studies, particularly of non-Western temporal systems, and of moments of encounter and exchange. Some of my own work is heading in that direction; in the sixteenth century, looking at the way that different kinds of communities responded to, interacted with, European time when they first encountered it.

And then I suppose the last thing I’d say is what the Germans would call Medialität – mediality. Time is inflected differently in different media regimes. We’re really conscious of that, of course, because of things like Twitter: can anyone concentrate when you have this constant barrage of very small little bitsy bits of information? But that applies, too, to questions such as: how did print change temporality? What happens when news cycles come on board in the seventeenth century, in particular ways, and so on? What happens when you think about the time of an altarpiece as opposed to the time of a letter? This kind of comparative work where you really bring media into focus is, I think, a really important part of where history of temporalities is heading. And it relates to interest, of course, in embodiment, in sensory perception, and so on, because media draws our attention, too, to embodied sensory reality. There are three things I think are interesting. There’s a lot more going on, but they are three that are great!

Oh, absolutely. They sound like three of some of the most important dilemmas or questions that we could ask as historians. I think that’s wonderful. So, what are some of the common misconceptions that you deal with when you talk about your research?

I think a lot of people think that all I think about is clocks and calendars! And, in some ways, you know, I do play into that a little bit. In my work I’ve increasingly become interested in clocks and calendars, because they do have really important implications for how time is experienced, how time is controlled, for others, and normalized. But the history of temporalities is much more than that.

I think one of the people who was really influential for me early on was Paul Ricoeur in his work on time and narrative. Just simply seeing the way that every text unfolds as a way of emplotting time; every performance or action involves a kind of temporal shift; every cycle of your feelings, your emotions, is something that unfolds in time. So in fact, every single object that you look at as a historian, every source that presents itself to you, you can ask a question: what is this doing with time? How is it experienced in time? How is it making time and so on?

So, I would say I try sometimes to drag people away from clocks and calendars and say, well, whatever source you’re working with, what is time doing here? Just like you could say, what is gender doing in every source, what is space doing in every source, and so on. So that time becomes its own category of analysis, and then we can develop distinctive methods for its analysis.

I suppose the other thing which is a very common misconception is that, because I work on the Middle Ages and into the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, that somehow I must be dealing with a really radically changeless environment. People think that peasants just sat around doing nothing all day, not really knowing what the time was. And if they did know the time it was because they’d been bludgeoned into it by some awful priests from a kind of over-controlling parody of religion, be that Islam, be that Catholicism, or so on. And so I often have to do some work to show the nuance and the interest in religious temporal systems and the ways in which control was resisted – that control was plural and variegated across institutions, and that there was conflict and variety present in that pre-modern world. So that’s another common misconception that I try to do a little bit of work to unpack and to trouble.

Let’s zoom in a bit closer now on your DECRA project, which is entitled The Sounds of Time, which is a fantastic title, and one that certainly makes me as a historian of sound very excited as well. Can you summarise what you’ll be focusing on as part of this project?

So, I wrote the proposal as a kind of history of musical clocks. I thought, there’ve been so many histories of just clocks – but what about the music that was played on them? And I came upon this by working in a small archive in a Belgian monastery where they have a clock that played a particular Latin ecclesiastical chant in honour of the Virgin Mary. And I delved deeply into the history of that institution, and that melody, to see the ways in which it was connected to that particular order’s interest in connections with the papacy, particular debates over the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary, and the hegemony of the Dukes of Burgundy. And I thought: ooh, this one object is extremely interesting!

In my early work, I’d been really synchronic. I wrote a history of temporality in the fifteenth-century Low Countries [The Fullness of Time]. It’s about three towns, and it’s very specific. But I wanted to do a history that was diachronic now and dealt with change, but which remained anchored in the practices of microhistory, which is, I think, such an important method for us to be using, you know, à la Ginzburg or Natalie Zemon Davis, and so on.

And I also wanted to start thinking a little bit more about global history. And I thought, well, to do that you have to do that sort of micro-global history of the kind that John-Paul Ghobrial is advocating for, and others, of course. So a musical clock, if I can find it in enough places over a few centuries, might be a little window into a world of what mattered, at least to the people who were purchasing and installing those clocks.

And then a kind of history which I’ve talked about elsewhere is a history of possibilities: how might these objects have been perceived? How might people have received these melodies? Were there contradictory possible responses? What evidence might we gather about reception? That’s incredibly hard; so, you have to be wildly speculative. That’s not something that troubles me too much. It troubles some historians, but I like speculation – I think it’s fruitful to say: ‘perhaps’, ‘maybe’, ‘this could be’, using the kind of frameworks of course that you historicise very carefully from the source record. But, nonetheless, you can take a bit of a walk on the wild side!

That project emerged from that little archival encounter. But I’ve always been interested in sound – I have a Music degree, like I said before. Sound is something which evaporates, so it’s very temporal. But it’s also involved in our memories – we recall sounds, and sound also draws our attention to those questions of mediality that I mentioned earlier, and the senses – it de-centres us from our common logocentric and ocular-centric ways of thinking and perceiving. So it provides a kind of useful triangulation point with time, a different window for coming in at the question of how time might be perceived or experienced. I think that’s why I turned to sound.

The other thing which I’ve always been interested about in sound studies, which is a hugely transdisciplinary field, is that sound studies has often been very modern in its focus. So there’s a lot of work like Veit Erlmann’s and others’ (), and where scholars consider recording technology. In that case, there’s sort of sometimes a way of even accessing something like the sounds, but how do you historicise that? I wanted to be a medievalist and early modernist who was engaging with that new scholarship – I’d had wonderful conversations with a brilliant musicologist in London, Emma Dillon, who wrote a really important book called The Sense of Sound, which showed to me some of the ways that sound could be a productive analytic. So, I wanted to do sound studies before modernity.

And I also wanted to ask a question of sound studies, which is: what does sound studies do with music? There are a lot of sound studies scholars who are not trained in musicology. But musicologists, of course, have been talking about sound for generations, and they’ve developed really interesting and wonderful techniques for dealing with sound. I’ve written on this, actually – there’s an article for Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, which I wrote with Miranda Stanyon about how historians have often been very wary of music because you need to do a lot of intense training to read it. And also because it’s able to position it as a kind of elitist question. So, you know, why would you be interested in opera, if you can study the cries of the street seller?

Now, I’ve always thought you can study both, and you don’t need to exclude one, you don’t need to perform an exclusionary manoeuvre – a bit like, you know, in history of temporalities, you don’t need to perform an exclusionary manoeuvre against the history of time as it’s been previously practised. You can develop a conversation, a dialogue that integrates further and moves towards a fuller understanding of what methods we might be able to deploy and exploit. So there’s a sort of methodological question there about how the music of the clock related to the sound of the clock.

And, then, I’m also really interested in the way sound relates to noise, sound relates to silence, sound relates to political and ethical commitments. There are always interesting analogies you can draw between musical cultures and wider cultural processes and social practices. They’re always tenuous links – they’re always little analogies – but I think they can be quite productive in helping us to come at the question of how societies are ordered, controlled and so on.

I’m always struck in reading about histories of sound about how heavily shaped the field is by particular microhistorical approaches. And a lot of historians who write about the history of sound in a particular place or a particular time, tend to emerge out of a very close, almost communion with the archives, sometimes over a whole career. And what is often missing is a sort of broader connective, or global or connecting approach, I think, and it’s so exciting to me that that’s one of the things that you’re aiming at with this work. It helps maybe connect some of the really interesting theoretical islands that we have within this exciting field into some territory that is a little more expansive.

You know, I remember being asked a question at a job interview, actually for the job I got at Birkbeck in London, by Filippo de Vivo, who’s a wonderful practitioner and theoretician about the way we do microhistory. And he said something like: “how do you relate the scale of microhistory to the broader question of generalisation?” And I gave a truly terrible answer! But, in a way, I think that there is no really good answer to that question. I mean, I don’t know exactly what Filippo would say about it, but I think he would probably agree that there’s always a kind of leap of faith, from the fact that your small might illuminate the large. To me, you know, there has to be a commitment to the small, and you’re right to say that historians of sound have to listen carefully. You can’t listen at a distance – you have to be present with your object. You can’t do like Franco Moretti, distant reading, I don’t think. I mean, I don’t think you can meaningfully do that to the history of sound. You have to be attentive and careful.

Absolutely! I can’t wait to see what you come up with that over the few years of your DECRA.

Something that I couldn’t help but notice on the beautifully put together project website for your work on the Sounds of Time is a tantalizingly brief section that outlines or maybe even teases a proposed new musical ensemble called Cantus Temporum. Can you tell us a little bit more about this? Or is this something that’s still maybe a little under wraps?

Well, it was going to happen, and then the pandemic hit! I have a background in choral music – before I left for London I sang quite a lot, worked a couple of opera contracts, directed the college choir at Queen’s College, and I’d always been looking for a way back into doing a little bit more musical work when I came back to Australia – and with these ARC grants, you always have to have all bells and whistles. One of the things which I wanted to do was to bring some of the polyphony of the fifteenth century to audiences, and non-standard audiences. So I pitched the idea that I’d form a little ensemble and we’d bring a performance event with some singing of polyphony, some singing of the chants that would be played on these clocks, and then some interpretive material around it to scaffold, so that people knew what they were listening to and why it might have mattered and why people might have been interested in it in the past.

The aim is that in the coming year or so there’ll be a small little six-voice polyphony ensemble bringing to you the sounds of time from the fifteenth and sixteenth century – the songs that were played on the clocks of Strasbourg, that were playing in the Devotio Moderna houses of the Low Countries in the fifteenth century. It will also be as it were a return from retirement for me to direct some music and to have some fabulous Melbourne musicians bringing that music to different parts of the country.

I love projects like this that do bring a different way historical context to life in a way or that encourage us to think across registers or across genres about a particular historical time.

I still think back to when I was a PhD student hearing Una McIlvenna singing some of her texts in a presentation – there’s something powerful going on in situations like this. And it makes me think: I mean, I feel as though the ARC Centre for Excellence in the History of Emotions has got a really good track record and has modelled so many of these kinds of projects on reviving and reawakening past historical contexts and performances and arts practices,

I suppose you could say on the Centre that one of its great achievements has been bringing pre-modern history to really diverse communities across the country. And those partnerships with cultural institutions, with festivals, the educational outreach has been a really powerful way of reminding the country, I hope, in various small ways, and some big ways, that pre-modern history is still shaping us and is still able to shape us, is still a resource for us to learn from and to think about possibilities for the future. So I’ve loved the work that the Centre’s done. And I think it’s been really important for Australia and for the world.

I think that one of the things which has marked the Centre’s impact has been a genuinely transdisciplinary approach – that is, it was never just historians; it also involves musicologists, literary critics, art historians. People felt they could participate because of that really lovely – and I think this is a genuine hallmark of Australian pre-modern studies – that genuinely inclusive, generous, kind approach, which is caring, and wants to look out for ways in which we can help each other and help the field flourish.

I think, too, as someone who doesn’t do medieval, early modern history as someone whose research is limited to those centuries that we would conventionally think of as the modern, the methodological openness and creativity of historians of the pre-modern world, especially those associated with the Center for Excellence in the History of Emotions, but not limited to that group, that has been such a source of inspiration and excitement, the fact that this group offers an opportunity for experimentation methodologically, or theoretically, is something that has an enormous value, I think, to the wider Australian historical community.

I think there’s a long legacy there of really powerful and interesting scholars, many of them women, in Australia. Patricia Crawford famously, and then the first head of the Centre, Philippa Madden – she was a historian who was very, very influential for me – actually, I knew her as a child. Her generous vision for the Centre was shared with other people, Stephanie Trigg, Charles Zika, Andrew Lynch, and many others. These are people who never shut down a conversation, they’re always looking for a new and exciting idea to be generated. And that’s partly because to be an early modernist or a medievalist in Australia, you always have to have a hugely broad outlook, because probably you’re quite by yourself in your department – you might have one or two colleagues, but not many. And so you always have to be looking out to others to enrich you.

And, you know, partly, it’s also the luck of the personalities that they’re also just extremely generous people who are prepared to listen carefully to others. And I always feel, and this is a pitch for the medieval and early modernists, that we always have to be across what’s happening in modern history, too, because that’s the theoretical environment which is inflecting our practice. Modernists can ignore us a lot more, right? Whereas we have to be in genuine dialogue. This is my slight moment of pride in the area that I study. I’m genuinely, constantly amazed by the intellectual curiosity and vivacity of my colleagues who are reading in anthropology and sociology. They’re talking to colleagues in Indigenous Studies, they’re thinking with their modern historian colleagues, and so on.

Because I do think that there’s probably a shared commitment to the sense that all histories are histories of the present in some way. That’s not to say that the past and the pastness of the past is not important. But if history isn’t speaking into present conversations and isn’t in dialogue with pressing political or ethical or cultural commitments of the present, critiquing them, sometimes providing support for different standpoints, then, you know, there’s not much point in doing history. So there has to be a kind of commitment to how the past is being shaped by the modern, and how we are also, through our sources, doing work that relates to questions of the present.

In thinking about the sort of collaborations that have been so central and are so central to your field, it’s a great opportunity for us to think a little bit about another project that you’re working on at the moment. So alongside your teaching, and your work on the Sounds of Time, you’re also one of the chief investigators on a new ARC Discovery Project called ‘Albrecht Dürer’s Material World’ (https://www.duerersmaterialworld.org/), alongside an all-star international team, including Melbourne’s own Jenny Spinks and Charles Zika. Can you tell us a little bit about this project as well?

This is a wonderful project that I feel incredibly honoured to be part of. It’s led by Jenny Spinks, who’s a really stunning scholar of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century German speaking lands and northern Europe more generally. She’s always had this brilliant capacity to join together the study of the material world and print culture. A number of the scholars in fact linked to the project are really wonderful people – Ed Wouk, Sasha Handley, Stefan Hanß in Manchester, Dagmar Eichberger in Heidelberg. They all have this interest in how materiality shapes the way that we might re-approach the past.

We’ve taken an iconic figure, Albrecht Dürer. There’s a fabulous Dürer collection in Melbourne at the NGV, and also a wonderful collection in the Baillieu here, so there’s an Australian collections angle. But he was also deeply enmeshed in the world of craft production, the material culture and life of Renaissance Nuremberg. The idea is to take objects and manufacturing processes and materials from that period, and place them alongside Dürer’s output – prints, drawings, and so on – to see what we might learn that’s new about these incredibly famous, iconic images of the sixteenth century, when we put them in the material frame.

Already there’s been some remarkable work – Charles Zika’s doing really interesting stuff on candlesticks, Jenny’s doing very interesting work on the kinds of goblets and cups which are held by various figures. In my own work, I was given this project by Jenny; she said, ‘why don’t you work on the sandglass in Dürer’s Melancholia?’ And I kind of freaked out, because, you know, Dürer’s Melancholia is one of the most studied things in the history of the universe!

It got me into some people I’m really interested in: the Warburgian tradition following Aby Warburg. You know, the famous book on Saturn and Melancholy, which really engages with Dürer on this point.

But now I’m looking at the production of sandglasses. What’s inside the sandglass is a really interesting question – how might it relate to what’s happening in the print? I’m looking at sundials, another product which Nuremberg was very famous for, produced using ivory traded up from North Africa; and the mathematics involved there, it’s extremely interesting – Dürer gets quite into that too, he writes about it.

And then, of course, there are the other objects in the image: scales, measurement devices, bells, again, for ringing the hours, signalling time. These objects, when they’re vivified in the prints, give us an insight into the particular social-material-cultural world that generated Dürer, and which Dürer was helping to reshape through different kinds of sensitivities to the material. He’s famously the son of a goldsmith, trains as a goldsmith, so it’s a very intimate interaction with materials and the processes of embodied knowledge, which have been so much at the forefront of scholarship in early modern studies in recent years.

The project gives us a chance to engage with that scholarship, too – the work of people like Pamela Smith on the Making and Knowing project. So it’s an incredibly dynamic space. There’s going to be a big exhibition in Manchester, the catalogue’s [Albrecht Dürer’s Material World] already been finished for that. And we’re looking forward to what will happen in Melbourne when we bring out the big international crew of Dürer scholars, and we make this a kind of real moment for engaging again with this figure who’s really important for the way we image the world.

You know, there’s a lot of Dürer that remains present for us. And there’s a kind of way in which Dürer remains a figure that people just keep returning to, to re-vivify and alter the way that they are seeing the world and interacting with the world. So paying attention to Dürer’s feathers, paying attention to Dürer’s tortoise shells, paying attention to the work, materials, fabrics of a bedsheet – all of this is totally new work, which is going to, I think, change the way that we approach Dürer and also the materiality of the early modern world.

So one final question: you’ve been so generous in your answers. You’ve given us such a great sense of where your work fits, what’s important about it, and importantly, who has informed that as well and what the wider sort of world that it belongs to, the wider community.

Related to this, I always love to ask guests on this show about the formative ideas and thinkers and texts that they’ve come across that have shaped them as scholars, I think you’ve already given us a really good sense of that through your discussions of the several exciting angles that you’re working on, that you’re researching at the moment.

But if you had to nominate any other sort of top books or works or ideas that have been essential ingredients in your research life, what would they be? I suppose in a sense I always love hearing musicians talk about their favourite albums, or artists talk about their favourite novels and why. And I’m hoping that with this question, we can give a sense of the excitement and the joy of doing history through influential works in the same way.

It’s such a difficult question, because there are thousands of books which are really important. I mean, I’ve been thinking again about Miri Rubin’s great work on narrative and the way in which narrative is used to make forces of violence work – that famous book, Gentile Tales, on accusations of desecration of the eucharist, but given I’ve already mentioned Corpus Christi, I probably shouldn’t talk more about that.

I would love to talk maybe a little bit about Jacques Le Goff, and his essays on time and work in the Middle Ages, the time of the church, the time of the merchant. His work is constantly full of little insights, fantastic generalisations, things which you may wish to totally disagree with, but which will be completely productive for the way you think about the way you do history. His emphasis on the city as a site of innovation, of cultural exchange, but also of exclusion, of course; his fantastic essay on the symbolic ritual of vassalage in that collected work, Time, Work and Culture in the Middle Ages; two or three pages on the medieval exemplum tradition, in his book, The Medieval Imagination.

There are some thinkers who, because of their deep immersion in the sources from a period, are able then to zoom out to see further than others – I think of Jacques Le Goff as one of those people. And every time I re-read an essay by him, I get something new – I may return to my work and then disagree with myself in different ways. So I think Le Goff, you know, of the classic historians of the Annales (and you could choose any one of them to talk about), he’s the person who I think I would turn to, to think with most.

And then there is Natalie Zemon Davis, and then life is transformed into the most beautifully ethically committed, rigorous, generous scholarship that you could imagine, and written with such clarity and such ease. I think we do need to pay attention to history as an art – in Melbourne, of course, you have to mention Donna Merwick when you think about history as an art and, of course Greg Dening, too. But it was from Donna Merwick that I first heard that sentence: “history is an art”. And I think paying attention to prose style – Natalie Zemon Davis is an example, Greg Dening, Donna Merwick – with their experimentation, their willingness to move outside the bounds of what might seem normal historical prose, has also been hugely, hugely inspirational. I haven’t had the chance to do it much yet myself, because medievalists perhaps have a little bit more of an allergy to it than other historians.

That sense of history as an art has always been a huge inspiration. I remember at a friend’s place in Berlin once picking Dening’s Islands and Beaches off the shelf and reading a couple of paragraphs and not being able to put it down. And there are very few books like that which you come across, which you remember where you were when you read them: Augustine’s Confessions – that’s another book. You remember where you were when you read that book, and you hear someone wrestling with what it means to be in time.

This is going to sound terribly old-fashioned, but I still think it’s really interesting: Clifford Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures and the essay on the Balinese Cockfight. Now, if you read that, and aren’t inspired to go out and read in cultural history, to attempt that style of analysis, to see if it works – it might not, but to see if it does – I think some part of you as a historian might be dead if you can’t respond to that!

We can critique it – there’s always a billion ways to critique Geertz – you can critique anyone. But there’s something wonderful about the way that that’s written, in its literary style, in its desire to make big connections from small things. And its desire to spend time reflecting on the ways that we make meaning with each other.

Now, you can say there’s too much emphasis on making meaning, there’s not enough on dissonance, about failure, about process and change – and all of that is true, but nonetheless, I think that essay, like Natalie Zemon Davis’s work from the ’70s on processions in Lyon, like Dening’s ‘Writing, Re-writing the Beach‘ – or whatever it is, like Le Goff’s famous essays – they’re works which will provoke, they’ll annoy you. They will then inspire you and you’ll be able to keep – this is very classical, this sounds very medieval – you’ll be able to keep drinking at the wells of their antiquity. Because it will keep nourishing – at least for me – it keeps nourishing the thought that being a historian matters. And that the way that we present our history matters as new ways of experiencing the world. You can always be told you’re living in the past with history. But I think history is always a really interesting way of re-encountering the world as we live it.

Wonderful answer. Thank you so much for that. I love asking this question. I love hearing historians’ answers to this because it always fills me with a renewed passion and enthusiasm and excitement for my discipline as well. And you know, I can remember where I was when I first read Clifford Geertz on the Balinese cockfight and it sort of brings me back to the place of being someone first getting excited by the openness and the possibility and the craft and joy of history as well.

I love that each one of these texts you mentioned sounds like the perfect jumping-off point to a lifetime really of thinking and re-thinking some of the most important questions we can be asking as historians really.

Thank you so much, Dr Matthew Champion, for talking through at such generous length, your work, where it sits and where your broader field is. It’s fantastic to be able to welcome you to the SHAPS community at the University of Melbourne. Thank you so much, Dr Matthew Champion.

It’s been a real pleasure – thank you so much.

To learn more about Matthew’s project Sounds of Time and to listen to some of the music included in the project, see the project website and exhibition.