Virtuality and Materiality: Decision Making in the Treatment of Margel Hinder’s Construction With Perspex Corners (Flight of Birds)

Paul Coleman

Shifting Forms: Temporal Developments in a Material World

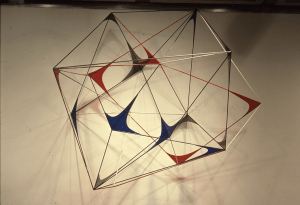

Margel Hinder’s Construction with Perspex Corners (Flight of Birds) is a modern abstract assemblage of welded steel bars and Perspex triangles. It is characterised, like much of her work, by strong angular lines and an abstract geometry. The shapes formed by the interrelation of the bars shift and flow as the work rotates (like the flight of birds[1]) around its central hanging fixture and with the changing perspective of the viewer. The ideal rationalist concept of a static, fixed identity is thrown out the window. The work refuses capture. There is no front-facing side, no singular point of return. It is in constant flux. It casts virtual planes that constantly actualise, fluid forms becoming and evolving for interpretation within the eye of the observer. Understanding this temporal, conceptual relation between sculpture>world>observer was essential to appropriate decision making.

This ungrounded, refusal of identity to be subjugated back onto itself is further driven home by the historical fact the work is a reproduction. Originally built in 1955, it was rebuilt in 1979 likely due to its destruction in transit – as was the fate of many of Hinder’s sculptures[2]. Thus forever problematising the authentic aura – contra Benjamin – of the work and diminishing the holy, untouchable ‘original’ materiality. However, in light of Hinder’s apparent involvement in the (re)creation, and the – soon to be discussed – emphasis on temporality and linkage between object <—> observer, this problematised materiality is beside the point. What is of interest, is the moving away from the Same. An original against which identity is determined. That is a movement towards the simulacra. Or perhaps it is simply Construction with Perspex Corners 2.0 – new and improved (now with sturdier Perspex!). Regardless of where one lies in the identity continuum between fixed and fluid, it must be conceded to speak of Construction with Perspex Corners is to speak of at least two distinct material constructions of a singular concept/work – a work that has temporal movement as an essential aspect of the construction.

Additionally, the work depends on the transmission of light, through the Perspex, against the metal bars and to cast shadows on a nearby wall. This effect, again, moves beyond a static, fixed identity and becomes part of an assemblage of interconnected relations.

The interplay between light>object>observer is to be considered an essential element of the completed piece alongside the temporal, and the material considerations. Again the appropriate preservation of the work depended upon an understanding of the concepts built into the structure and their interaction and movement into the wider environment.

This open-ended flux is conditioned upon the interpretation of these virtual planes by the observer, and are developed through their free movement through space and time. The shapes created by the negative space between intersecting metal bars fluidly ebb and flow, constantly in motion. Temporality is one of the major components of this work and preserving this ability to move, to create shapes and the ever shifting virtual planes was integral.

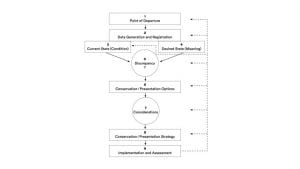

Treating the Material Treating the Immaterial

Of concern during the conservation treatment was a bent metal bar on the lower face that caused two problems. 1) It disallowed the reattachment of a Perspex corner which in turn disallowed the transmission of light through the Perspex to project its coloured shadow on nearby surfaces, and 2) The distortion of the bar altered the sharp geometrically shaped forms created the movement of the metal bars. The resulting forms were curved and far from the initial construction of the work. Underpinning these concerns was the temporality of the work. Movement is a necessary condition. Being able to safely suspend the work to allow this movement would be, of course, essential. We used the Cologne Institute of Conservation Sciences Decision-Making Model for Contemporary Art Conservation and Presentation to guide our treatment. We identified a major -5) Discrepancy between – 3) Current State (condition): bent metal bar; detached Perspex; unsure if suspension is possible and – 4) Desired State (meaning): the free movement of suspended work allowing the build up of shapes and spaces that ‘develop and disappear develop and disappear’[3]. But importantly, these shapes should, from reading the rest of the piece, hold sharp, bold lines. The bend in the bar diminishes the sharp geometric lines and angles. Instead, always creating a curved plane that contrasts and disrupts the rest of the piece. The curvature of the bend draws the eye and is inconsistent with the remainder of the sculpture.

We used the Cologne Institute of Conservation Sciences Decision-Making Model for Contemporary Art Conservation and Presentation to guide our treatment. We identified a major -5) Discrepancy between – 3) Current State (condition): bent metal bar; detached Perspex; unsure if suspension is possible and – 4) Desired State (meaning): the free movement of suspended work allowing the build up of shapes and spaces that ‘develop and disappear develop and disappear’[3]. But importantly, these shapes should, from reading the rest of the piece, hold sharp, bold lines. The bend in the bar diminishes the sharp geometric lines and angles. Instead, always creating a curved plane that contrasts and disrupts the rest of the piece. The curvature of the bend draws the eye and is inconsistent with the remainder of the sculpture.

A plan was mounted to straighten the bent bar, allowing us to reinstall the detached Perspex which in turn would allow for an approximation of the originally intended spacial relation between the intersecting metal bars, formed shadows, and their impression onto the observer. With the bar straightened, the work was hung to test its structural integrity and to revive and restore its free floating movement – to allow for a proper viewing of its virtual planes actualising into existence. The decision making model is, itself, open-ended and dynamic. It allows looping back to reinterpret, rework problems that arise. This requirement occurred during our implementation steps. Where straightening the bar started to feel unsafe and likely to cause more issues than solved if we proceeded. So, the implementation plan looped back and we re-assessed our strategy – deciding to lightly shave a millimetre or two off of the Perspex to allow for a flush fit. With the Perspex reattached, and the bar straightened, Construction with Perspex Corners (Flight of Birds) was able to traverse through space and time to be properly interpreted by the observer.

Our treatment followed a traditional path of (attempting to) return material conditions to a semblance of origin point-zero – i.e. as close to original manufacture as ethically permittable – but at all times the guiding principle that led down that path was based upon the consideration of the temporally initiated development of forms and the open-ended shifting virtual planes. Reattaching a detached Perspex triangle to its corner restored more than the physical condition of the work, it reinstated the necessary components of the light>object >observer relation. Straightening the metal bar went beyond simply reinstating the original conditions of the object, it reinstated a more accurate ability for the work to develop its interior forms. Overall, the decision-making and treatment steps moved towards aligning the material state of the object with this open-ended flux. The work’s tendency to evade capture, its refusal to be pinned down to a static identity, its projected impression onto the observer, held as much importance to Hinder’s conception as the material construction.

[1] Freé, R 1980, Frank and Margel Hinder: 1930-1980, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, p. 58.

[2] Cornford, I 2013, The Sculpture of Margel Hinder, Phillip Mathews Books, Willoughby.

[3] Margel Hinder interview with Esther Corrsellis qtd. in Cornford, 2013, p. 100.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Bathurst Regional Art Gallery Director Sarah Gurich and Bathurst Regional Council Collection Manager Tim Pike, who are a long term partners of the Grimwade Centre and have provided object based and work integrated learning opportunities for graduates. The treatment was undertaken as part of Conservation Assessment and Treatment 2 with follow students Isabelle Legg, Emma Morrison and Georgina Duckett.