The Many Hands of a Treatment: The Conservation of The Railway Hotel Pimpama

By Rachel Davis

There is perhaps a stereotypical image of a conservator that many might have in their heads. That image might consist of a lone person, tucked away in a hidden lab, methodically swabbing away at a painting. But that has been far from the case in the treatment of one particular painting; The Railway Hotel Pimpama, by an unknown artist.

In fact, many have had a hand in the conservation of this painting. Railway Hotel was selected to be treated as a group project. But our group (consisting of paintings conservation students Jordan Aarsen, Sasha Kozyrevich, Paddy Mitchell, and myself), were not the first conservators to undertake treatment of the painting while it has been in the care of the Grimwade Centre. Additionally, our treatment also showed the benefits of working with a large team of conservators and what can be done with the support of many hands.

Previous Treatments

The Railway Hotel has been dated to around 1875. Now part of the State Library of Queensland’s collection, the painting is an important example of early colonial era painting in Queensland. This importance was explored further in Michael Houston’s Minor Thesis (2014), which was an in-depth study on the materials and techniques of the Railway Hotel.

The aim for our treatment was to complete the next stage in the treatment process, which had first been started at the Grimwade in 2014, by Houston and others. The condition of the painting at this time was not the best.

The varnish layer significantly discoloured the painting, and there were large tears through the canvas. Previous repairs of the tears were also no longer offering any support. The first round of treatment in 2014 focused on some initial tests, cleaning, and taking those first steps in addressing the issues with the primary support. Nearly every year since, treatment has continued. Various methods of removing the discoloured varnish layer with solvents and gels continued, and the tears were addressed largely using the Trecker system (for a useful summary, see Laura Hartman’s (2011) article: ‘A Useful Tool for the Repair of Gaping Tears: The RH Trecker’). By 2021, the painting was nearly ready to be lined.

Lining Treatment

Many of the previous treatment reports had suggested that the Railway Hotel be lined, and in an updated assessment of the painting, this is what our group decided to focus on.

Lining is a technique used in conservation to reinforce a weak or damaged original primary support. While a great amount of work had been put into the Railway Hotel to address the structural issues, it was decided that it still needed the extra support and protection that a lining could provide, as well as to reinforce the tear repairs that had already been completed. The primary support consists of a very thin cotton canvas, which is still susceptible to tearing and damage. As seen in above images, it also had staining from previous adhesives and cleaning.

First, the painting had to be prepped for the lining process. This involved some final mechanical cleaning, to further remove some of the stains and remaining varnish, which could potentially cause issues if heat, which we would be doing as part of the lining process.

We also faced some of the more fragile areas of the media. Facing involved pasting down strips of Japanese tissue paper over the tears and the edges of the painting, with a glucose based starch paste.

Then came our lining day. This meant a little field trip to the Grimwade Commercial Services (GCS) facility based at the Public Records Office of Victoria, where Principal Conservator, Paintings, Caroline Fry, and Graduate Conservator, Jessica Walsh, assisted our group, which also included supervisor Nicole Tse and John Hook, Executive in Residence at the Grimwade, in further prepping the painting.

To line the painting, BEVA 371 film adhesive and synthetic sailcloth were used. BEVA 371 was created for dedicated use in the conservation field, and its properties have been shown to provide long-term stability when used in lining treatments as was being undertaken in this instance (Bianco et al. 2015; Ploeger et al. 2014). The use of sailcloth was also chosen due to its stability, but also isotropic, a desirable quality to reduce areas of stress in the painting (Hedley & Villers 1982, p. 155). This was important for this painting, due to the number of tears that had weakened the support.

The BEVA 371 film and sailcloth were cut to size. Moving to the hot suction table, a layer of silicone release was placed down, then the sailcloth, BEVA, then the canvas, with a final layer of Mylar. The suction was turned on, keeping everything in place, and then the table heated to around 70 degrees celsius – enough to melt the BEVA film, and activate its adhesive properties. While suction was on, we had to be careful to make sure no ridges were developing, especially near areas of tension at the tear repairs, but also be delicate enough to ensure we were not possibly adding any further cracks to the media. After a few minutes under the heat and pressure, the painting was left to cool and set for a few days, before being returned to the lab at the Grimwade Centre. The lining had been successful, and now had to be re-stretched onto the strainer.

Re-stretching

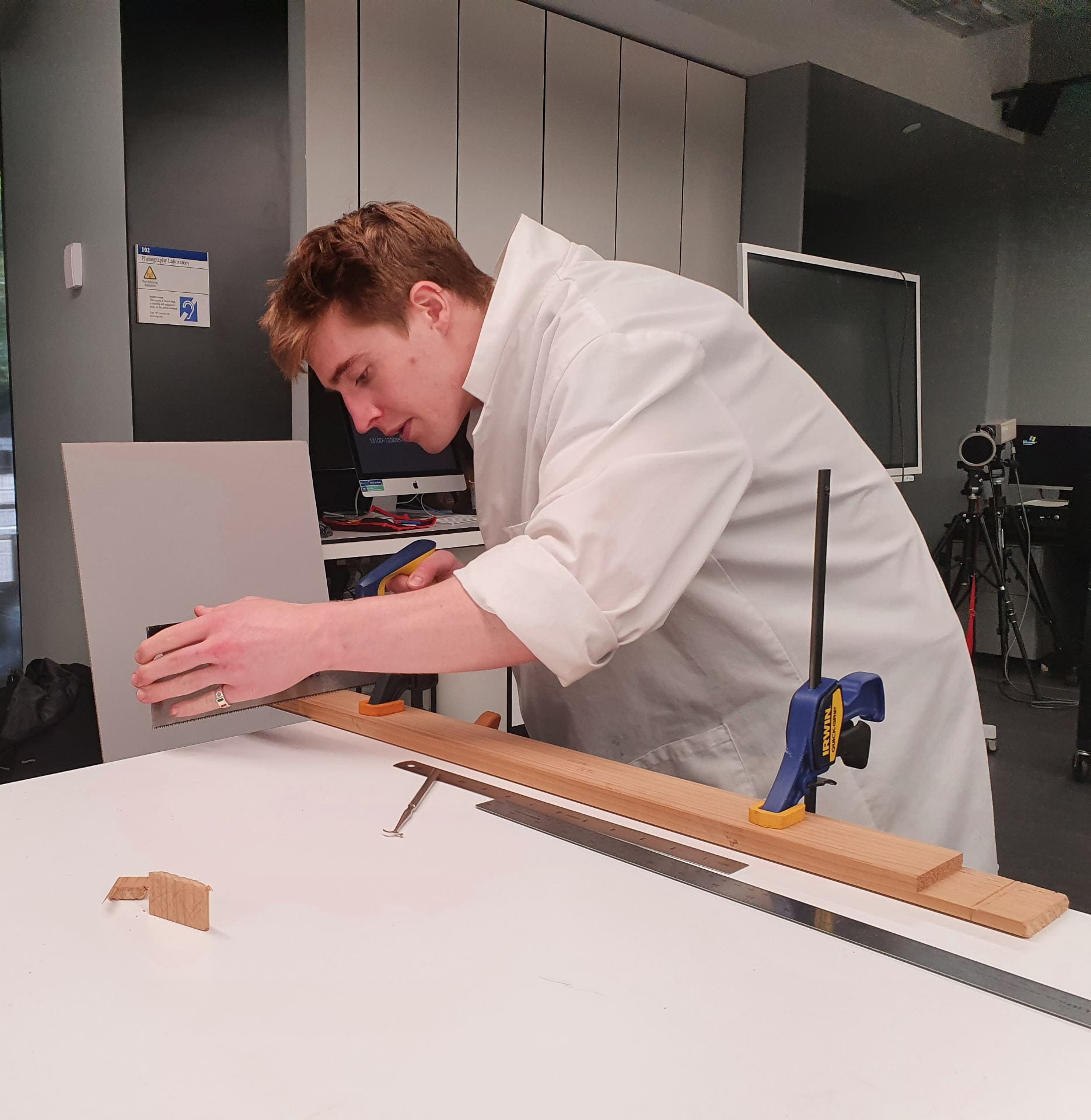

It was decided to reuse the original strainer, with some adjustments. Namely, beveling the inner edges, to reduce the damage which can be caused by the harsh vertices against the support canvas. A cross bar was also added to reduce damage from possible deformation of the wooden support and to increase its tensile strength.

After these adjustments, the canvas temporarily re-stretched back onto the strainer. To do this, the edges – now nicely straightened and stiff from our lining treatment – had to be gently bent so they could be pinned around the strainer. This was done with our hands mostly, and also light use of a hair dryer, the small amount of heat helping to slowly create the folds. After the folds had been created, the canvas was pulled in opposing directions and temporarily tacked down, then left to rest into its new position for about a week.

Finally, the canvas was then stapled down and the temporary tacks removed. The lining process and our turn at treating Railway Hotel completed.

Future Treatments

Many hands went into this treatment, and there will likely be many hands in the future to finish what needs to be done. Future students can possibly undertake infilling and inpainting around the tear repair areas, for example. I am sure you may see more blog posts in the future about the continuation of treatment on The Railway Hotel Pimpama.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to supervisor Dr. Nicole Tse, and to John Hook, Executive in Residence, for their help feedback and assistance.

Thank you also to the Grimwade Commercial Services team and in particular Caroline Fry, Jessica Walsh, and Jordi Casasayas, for their assistance during the lining day and use of the vacuum hot-table, and for feedback in regards to the strainer.

Thank you also to the State Library of Queensland, for giving students the opportunity to learn a lot from this painting.

Finally, thanks of course to my paintings group team members: Jordan Aarsen, Sasha Kozyrevich, and Paddy Mitchell.

References

Bianco, L, Avalle, M, Scattina, A, Croveri, P, Pagliero, C & Chiantore, O 2015, ‘A Study on Reversibility of BEVA®371 in the Lining of Paintings’, Journal of Cultural Heritage, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 479-485.

Hartman L 2011, ‘A Useful Tool for the Repair of Gaping Tears: The RH Trecker’, WAAC Newsletter, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 14-15.

Hedley G & Villers C 1982, ‘Polyester sailcoth fabric: a high stiffness lining support’, Studies in Conservation, vol. 27, Issue Supplement 1: Preprints of the Contributions to the Washington Congress, 3-9 September 1982 Science and Technology in the Service of Conservation, pp. 154-158.

Houston, M R 2014, ‘The Materials and Techniques of The Railway Hotel (c. 1875): A Reflection of Nineteenth Century Colonial Australian Painting Practice’, CCMC minor thesis, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne.

Ploeger, R, René de la Rie, E, McGlinchey, C W, Palmer, M, Maines, C A & Chiantore, O 2014, ‘The Long-Term Stability of a Popular Heat-Seal Adhesive for the Conservation of Painted Cultural Objects’, Polymer Degradation and Stability, vol. 107, pp. 307-313.

Tay, D 2014, ‘Major Treatment Condition Report’, treatment and condition report, Grimwade Centre for Cultural Materials Conservation, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne.