Early Female Printers in the Goold Collection

Huw Sandaver

Technical Services Librarian, Mannix Library

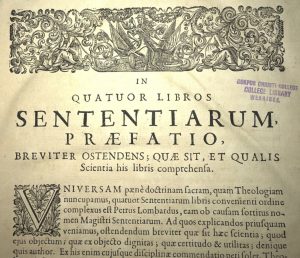

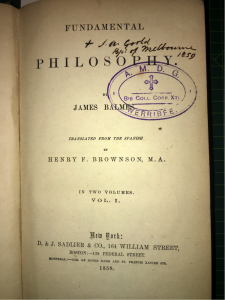

During the course of the creation of the Goold Collection in 2017, I came across three previously uncatalogued items of unusual aesthetic. All three are hand pressed items, published in Paris, ranging from the mid 16th to the late 17th century. I imagine that the items had landed in the “too hard basket” for so long because of the unique nature of the publications meant a giant headache for those tasked with the formal identification and description of the items.

The three publications were in some way concealing the true identity of the printers and, as it turns out, the three items represent emergent feminism in the publishing industry, a particular phenomenon in France, as the guild system in place there allowed women to take over and run businesses after their husband’s death.

The mystery of Saint Ambrose

The main challenge with the Goold collection lies mostly in the verification of provenance and linkage to Goold himself. The first item, Saint Ambrose’s Opera quatenus in hunc usque diem ubi ubi extare noscuntur omnia & eadem ad collationem exemplarium antiquitatis recognita, etc., although unrepresented on the handwritten inventory, was unquestionably Goold’s with his signature and “Archbishop’s Library Melbourne” scrawled over the title page.

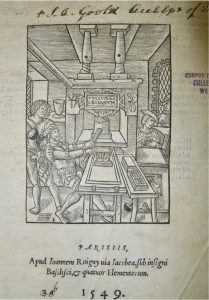

The first striking thing about the book is the unusual woodcut depicting a printer in his workshop, framed in the centre of the title page, which undoubtedly would have had some appeal to Goold as a book collector.

All is not as it seems, however, as the printers’ device is the mark of the printer Josse Bade, who was already dead by the time the work was printed in 1549. The title page states that the printer is in fact Jean de Roigny. The first theory I had about this strange discrepancy was that de Roigny had simply appropriated Bade’s mark in order to increase the prestige of his own print shop by association with a famous printer. In order to verify the theory, I consulted Jean de la Caille’s early catalogue entitled Histoire de l’imprimerie et de la librairie : où l’on voit son origine & son progrés, jusqu’en 1689 / Divise’e en deux livres , which revealed that Roigny had married Jeanne Bade, Josse Bade’s daughter, and rather than create his own mark, was printing in association with his wife’s name rather than his own. Women involved in printing either as printers’ wives or daughters tended to become highly educated and would have been involved in the business of printing, even if unacknowledged.

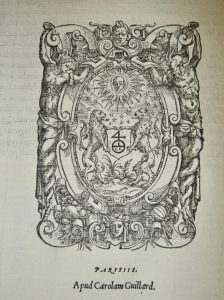

This was not the end of the mystery, however, as part way through the work, before volume two begins, another large printers’ device appears, taking up the entire page of the work, with elaborately italicised text stating “Printed by Charlotte Guillard”.

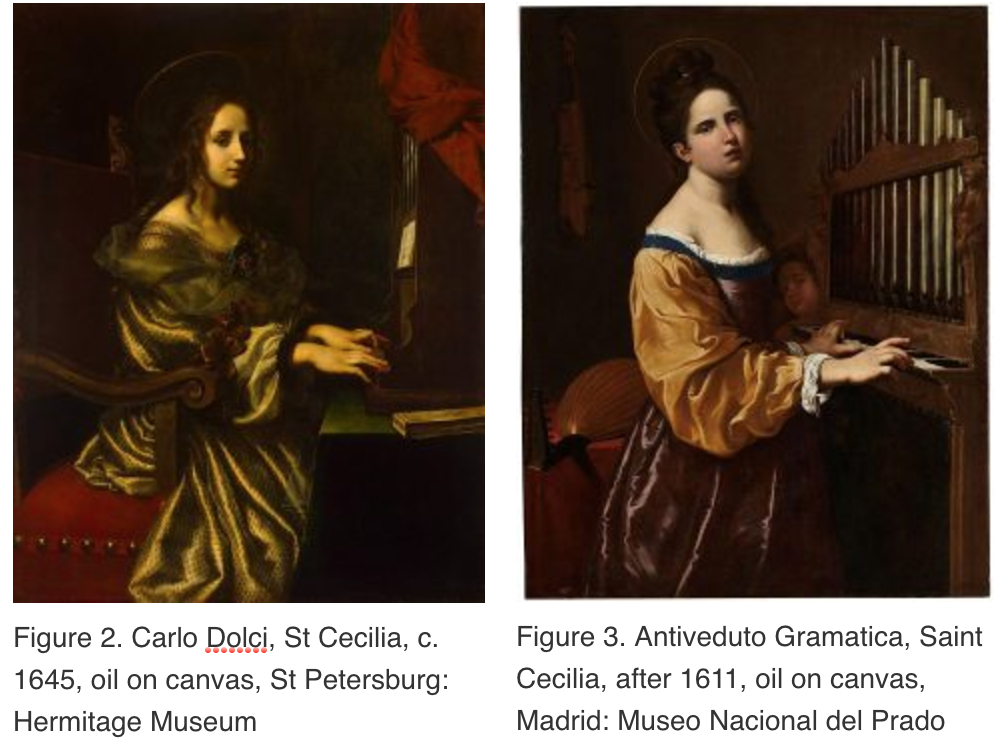

Charlotte Guillard (1485?-1557) was one of the most well-known of the French female printers, and one of the few who actually printed under her own name. While not much is known about Guillard’s early life, she wasn’t born into the printing industry. Her first husband was the printer Berthold Rembolt, whose device involved two lions holding a shield under a resplendent sun.

Rembolt must have held his wife in high esteem because Guillard is one of the only female printers of the hand press era to have had a portrait engraved (on the lower right of the woodcut below).

Interestingly, Guillard appears taller and more powerful than her frail looking husband, even though she kneels behind him, peering over his head.

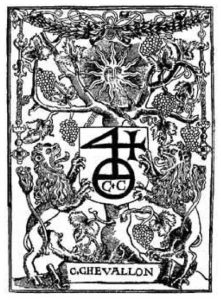

When Rembolt died in 1518, Guillard took over his business and operated under her own name for a period of time before marrying the bookseller Claude Chevallon. Chevallon basically appropriated the lion/sun motif that he had acquired through marriage (although there are two alternate versions featuring horses rather than lions).

After 1537, when Chevallon died, Guillard began printing again under her own name, finally merging her two husbands’ devices into something completely new, and much more pictorially ambitious. The two male devices, while interesting images, are extremely flat looking. Guillard’s amalgamation, as seen in Goold’s Saint Ambrose work, is a much more sophisticated image with a kind of proto-baroque trompe l’oeil effect of looking through a window. Guillard’s device frames her two past husband’s devices with something completely new and three dimensional

Goold (or anyone who owned the book) may not have even noticed the woodcuts, given the relative fine condition of the paper that Guillard’s devices appear, comparative to the title page, which have been much more exposed to the elements. Guillard, in fact, went to court with another other female printer, Yolande Bonhomme, to attempt to improve the quality of the paper supply in Paris. They argued that the paper quality was better controlled if they were able to buy it directly from the paper mill, rather than the (apparently unreliable) papermakers in Paris. They lost the case, and this most likely explains why the work in Goold’s collection is in relatively poor condition compared to other works in his hand pressed collection.

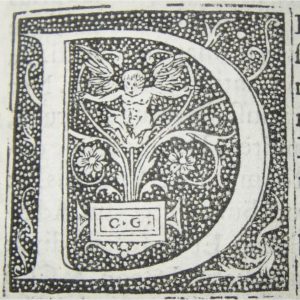

Guillard was a well-known and prestigious printer, why would she hide her device inside the work? Furthermore, the work is edited by Erasmus who had used Josse Bade as a preferred publisher, but after a dispute chose Claude Chevallon. This may be why Guillard’s device retains the initials C C as seen in the centre of the image. Guillard was known to have worked with other female printers (Yolande Bonhomme, in particular), so perhaps Guillard was working with Jeanne Bade, even though de Roigny’s name appears as the printer. Whatever Jean de Roigny’s or Jeanne Bade’s involvement, it appears to have been very limited or non-existent, as Guillard’s beautiful, signed floriated initials woodcuts appear all the way through the text, not just after the leaf where her device appears.

Furthermore, the colophon and print register which appears in volume one, at the end of the preliminary gatherings states yet again that Charlotte Guillard is the printer, this time dating the printing as 1550, while the title page states 1549.

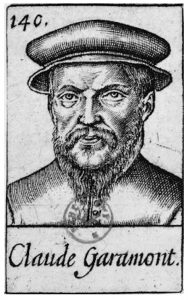

In examining the typography we can see that Roigny’s title page and Guillard’s colophon are printed with exactly the same type. One explanation for this is the typographer Claude Garamont, who had worked with Claude Chevallon and Charlotte Guillard in their workshop known as the Soleil d’Or in the 1530’s. After becoming a printer in his own right in 1545 Garamont invented a type (now known as Garamond) that Roigny had invested in and clearly had the rights to use. The examples show however, that Garamont’s type and the type ultimately used in the Goold St Ambrose work is subtly different to the type that Roigny actually invested in:

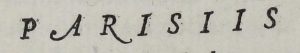

Garamont (1545)

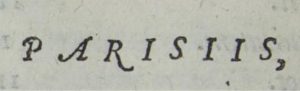

Roigny? (1549?)

So Roigny (or Jeanne Bade) and Guillard certainly had a strong association and quite possibly a business relationship but all of the type work in the Goold St Ambrose text appears to be entirely Guillard’s.

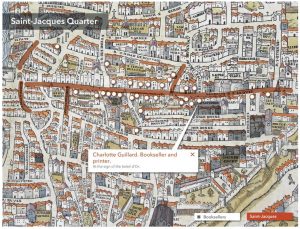

The possibly false title page, then, appears to be an academic joke, and given that the location of Guillard’s shop was next to the University of Paris (Shown as the Sorbonne on the map below), the joke probably would have been understood by her clientele, which were mainly academics, students and monks.

In fact, it wasn’t the first time de Roigny’s name appears on an Erasmian text printed by Guillard. A Greek New Testament published in 1543 also bares Roigny’s name and his shop was located very close to Guillard’s, then perhaps Guillard tended to work with Jeanne Bade, as an associate on some texts.

Guillard made a significant contribution to the Renaissance tradition of translating Greek texts into Latin, which were scarce after the fall of the Roman empire. Working with the translator Godefroi Tilmann, a Carthusian monk, Guillard published the first editions in France of the writings of Justin Martyr and Proclus of Constantinople.

Guillard’s Greek type is seen throughout the Goold St Ambrose text, and her work was known for its accuracy.

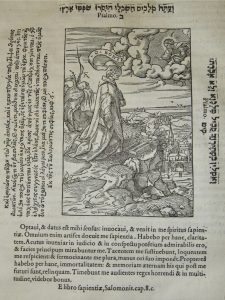

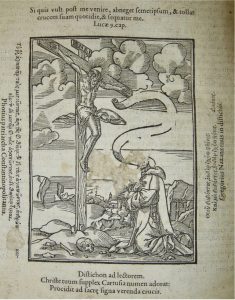

The work in Goold’s collection contains two woodcuts (one now slightly damaged woodcut on the final page) featuring the work of Tilmann, depicting a Carthusian monk in prayer framed by quotations in Greek and Latin.

In both woodcuts, out of the monks mouth appears to be a swirling writing scroll, presumably a symbol of words being directly delivered from God in the first woodcut

andChristonthecrossinthesecond.Thisis aninterestingmetaphorforthewriting and book production process, which is something that may well have appealed to Goold as a bibliophile. Whatever the meaning of the final woodcut, Guillard was certainly an ambitious woman, with a degree of sophistication that surpassed her two husbands and a reputation for fine printing that persists to this day.

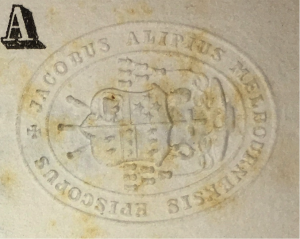

The Sign of Saint Peter

The second challenging item was also unquestionably Goold’s (and also bares John Fitzpatrick’s signature. Fitzpatrick was a close colleague of Goold’s who shared a taste in Baroque art and antiquarian books. The title page of R.P. Cornelii Cornelii a Lapide, è Soc. Iesu, in Academia Louaniensi Sacrae Scripturae professoris, In Pentateuchum Mosis commentaria, printed red and black states that the work was “printed by the widow of Pierre Chevalier”. La Caille fails to mention her at all in his Histoire but he does talk glowingly of Chevalier himself, stating that his edition of Florimond de Raemond’s Histoire generale du progrez et decadence de l’heresie moderne. was an extremely fine work. La Caille also tells us that Chevalier’s printer’s device is that of a knight rushing through a fire to save a city.

and that André Chevalier (the second named printer in Goold’s work) was Pierre’s son. The book itself is revealed to have been printed by a mother-son partnership, but I was no closer to finding out the identity of Chevalier’s widow.

The second point of call for discovering just who Chevalier’s widow was is Augustin Martin Lottin’s Catalogue chronologique des libraires et des libraires-imprimeurs de Paris who merely tells us that Chevalier was active around 1607. Finally, after consulting Philippe Renouard’s Imprimeurs parisiens, libraires, fondeurs de caractères et correcteurs d’imprimerie it is revealed that Chevalier’s second wife was called Élisabeth Macé who was the daughter

of the printer Charles Macé. Growing up as the daughter of a printer must have meant that Élisabeth was herself highly educated. There was also a precedent in the family. Charles Macé’s wife, Isabeau Morel succeeded him and became a printer herself, which is confirmed in Lottin’s work. Having seen her own mother become a printer naturally Élisabeth took over Chevalier’s business when he died in 1628. While she didn’t print under her own name, she made a radical change to Chevalier’s old printer’s device of the knight leaping through flames.

Unusually for a printer’s device, it is signed by the engraver Leonard Gaultier, known for his heavily symbolic and almost ridiculously detailed and dense engravings which attempted to visually depict Aristotlelian philosophy

Gaultier’s new printer’s device engraved for Macé is dated 1629, a year after Chevalier’s death. While still depicting the same motif, the device has a much more baroque sense of movement and drama. Poor Pierre’s initials have been shifted to a broken column, a common graveyard motif, and the background is peppered with buildings that look rather deliberately like phallic symbols. Even the gallant knight’s horse is anatomically correct! This is no old flat, medieval looking printer’s device. Even if Macé was unwilling to use her own name as a printer, the new device has a definite impact, which is almost cartoonishly baroque in nature. Given Goold’s penchant for baroque imagery, and architecture this must have piqued his interest.

Macé must have been an astute businesswoman, who, unlike many printers actually very precisely locates her shop in the colophon of the book, stating “Sumptibus viduae Petri Cheualier, via Iacobaea sub signo Diui Petri propre Maturinensis” or very roughly “at the expense of the widow of Pierre Chevalier, Rue Saint-Jaques under the sign of Saint Peter, next to the Maturins”. Luckily there is a near contemporary map that can be consulted, Benedit de Vassallieu’s Portrait de la Ville from 1609.

From the map it’s clear that anyone walking past Notre Dame to go to the University would have passed by Macé’s shop, which was also located directly next to the Trinitarian monastery, the monks being likely customers. Furthermore, the work itself seems to have been published to capitalise on the recent death of the author. Cornelius Cornelii a Lapide died in 1637, the same year that that the book was published. Macé obviously had a strong business acumen and was incredibly well educated. Macé herself quite possibly engraved a woodcut seen early in the work.

Although the head-piece uses the monogram P C, the work was printed nine years after Pierre Chevalier’s death. Macé went to the trouble of commissioning a distinctly new device, it seems likely that she also had all new woodcut decorations created. While she was not willing to put her own name to the printings, signing it as P C probably means that it is the work of Macé. Engraved vignettes are not usually signed, so clearly the monogram’s presence was a kind of statement in itself. Again the imagery looks strangely sexualised, as is a further decorative cul-de-lampe, signed with the cipher IL (probably Leonard Gaultier again, who was known to use many different letter combinations as ciphers, although this isn’t a listed one).

Although the head-piece uses the monogram P C, the work was printed nine years after Pierre Chevalier’s death. Macé went to the trouble of commissioning a distinctly new device, it seems likely that she also had all new woodcut decorations created. While she was not willing to put her own name to the printings, signing it as P C probably means that it is the work of Macé. Engraved vignettes are not usually signed, so clearly the monogram’s presence was a kind of statement in itself. Again the imagery looks strangely sexualised, as is a further decorative cul-de-lampe, signed with the cipher IL (probably Leonard Gaultier again, who was known to use many different letter combinations as ciphers, although this isn’t a listed one).

The ancient roman pagan looking imagery, being a baroque motif must have appealed to Goold on some level, and in this case is quite mannered in style, making the work one of the most intensely baroque looking of the Goold book collection now housed in Mannix Library.

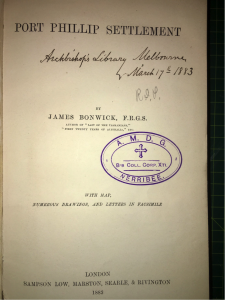

The Widow’s Syndicate

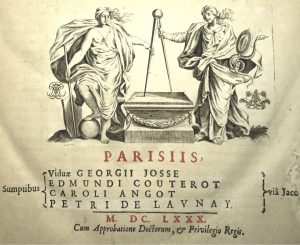

The third challenging item Dn. Guillelmi Estij S. Theologiæ Doctoris et Professoris Primarij, et Academiæ Duacensis Cancellarij, In quatuor libros Sententiarum commentaria… was again published by a widow. This time the “widow of Georges Josse” sits at the head of a larger collective group of publishers, one being Jean de la Caille himself, although mysteriously, in volume one of the text, la Caille’s name has been pasted over with the name of Pierre de Launay. De Launay was actually a bookbinder at the time of publication, although he appears to have been self-taught, and then forced to become a bookseller in 1686, after a separate bookbinder’s guild was created.

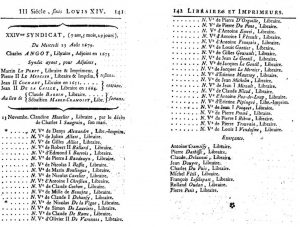

Since la Caille himself was involved in the production of the book, he has elucidated quite a bit of information about the people involved in the production of the book, although only really a passing reference to “veuve de Georges Josse”. At the end of la Caille’s book we start to see listings of Syndicates, which became important in France after the monarchy passed laws regulating the print trade starting in the early 17th century. La Caille tells us that Georges Josse’s wife was Denise de Heuqueville and that his daughter Marguerite married Charles Angot.

The work, then is a round-a-bout mother/daughter partnership in producing the text.

The printer’s device seen on the title page, featuring two mythological figures holding a compass immediately takes on new meaning.

On the left of the device we see the monogram of Georges Josse and on the right we see the monogram of Charles Angot. Having the monograms flanked by two mythological women, seems a rather pointed reference to the main producers of the item, since de Launay was probably the binder. Not much is known about Edme Couterot, except that his mother, Marie le Clerc was a printer printing under the name of “Veuve de Denis Moreau”.

Unfortunately la Caille doesn’t include any details on Denise de Heuqueville herself, but she seems to have exerted a heavy influence on her son-in-law. A year before the publication of Goold’s text, in 1679, we see Charles Angot at the head of a syndicate almost entirely made up of widows.

No less than thirty-eight widows were members of the syndicate in 1679. It seems, then that Angot’s syndicate acted like an early trade union and was set up to protect the widows from the harsh regulation of the French monarchy, which could have easily shut down small shops, claiming that no “master” printer was producing the works.

The appeal to Goold may well have been in the woodcuts that depict exploration, probably of the “new world” of South America, which he probably felt an affinity with having come to Australia.

Recent Comments