A Rare Example: Diana Scultori (Mantovana) 16th-Century Female Engraver

[The following post was written by Amelia Saward, student intern, Print Collection]

In sixteenth century Italy most women were confined to the social sphere. A female’s contribution to their family was generally through marriage and producing successions to the family line. For upper class women it also included paying house calls to other respectable women in order to maintain societal connections. Diana Scultori, on the other hand, was concerned with establishing her printmaking career, assisting her family’s income and maintaining prominent connections within the Mantuan court and in Rome and Volterra once marrying. An entrepreneur, she made efforts to secure her family’s income by using her works to gain commissions for her husband Francesco Capriani’s architectural career.[1] She belongs to a select group of female artists of the Italian Renaissance, even fewer of whom were printmakers or who had reasonable success in their own lifetime. She was the first woman to have signed her own name on her prints.[2]

Born to a Mantuan printmaker, Diana learnt her skill from her father, along with her brother Adamo. This was one of the only ways women were able to gain such an artistic education and the majority of female artists during the period had been taught by their fathers. In Diana’s case, however, he had not taught her drawing and so she relied on the drawings of others for her engravings. In her early career in Mantua she primarily based her works upon drawings by Giulio Romano and later on works from connections gained through her husband, whom she married in 1575, and the papal workshops. Even when the first drawing academy begun in Rome she was not allowed to attend.[3]

Although often referred to as Diana Scultori, she never used the name, as her brother did. Instead she referred to herself as Diana Mantovana and later included Volterra, in reference to her husband and his city of origin.

Diana was an anomaly in Giorgio Vasari’s Lives, mentioned in his second edition published in 1568. She met and impressed Vasari at only nineteen, when he came across her whilst at the Gonzaga court seeking material for the edition. He wrote ‘To Giovanbattista Mantovano, an engraver of prints and excellent sculptor, whom we have spoken of, in the Vita of Giulio Romano and that of Marcantonio Bolognese, two sons were born, who engrave prints on copper divinely; and what is more wondrous, a daughter named Diana who also engraves very well, which is a wondrous thing; and I who saw her, a very kind and gracious young girl, and her works which are very beautiful, was astounded’.[4] Vasari noted two sons. Diana, however, only had one brother Adamo. The other is likely to have been Giorgio Ghisi who was possibly a student.[5] Though he was incorrect in this detail, it is clear Vasari was much taken by the young Diana, evidently impressed enough to include her as one of the few women featured in the text.

As an entrepreneur, Diana requested and was granted a papal privilege in 1575, after she moved to Rome with Francesco. This gave her intellectual property rights and made it a crime for someone to reproduce, copy or sell her works without permission. Thus, she was able to control their distribution and establish a prestige to attract courtly buyers, which also assisted her husband to get architectural commissions.[6]

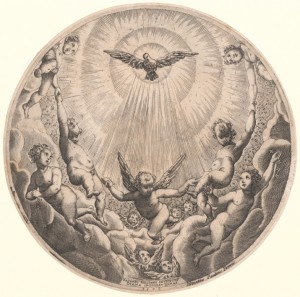

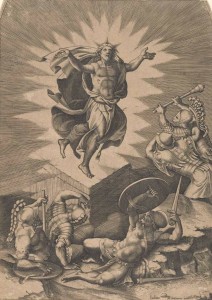

Her engravings depict a mixture of religious and secular subject matter, and examples of both are held in the university’s collection. Latona Giving Birth to Apollo and Diana on the Island of Delos, is an example of her secular works. The engraving is based on a preparatory drawing by Giulio Romano (Louvre, Paris) for a painting on the same subject (Hampton Court, London).[7] The scene from classical mythology, taken form Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a text of great inspiration for sixteenth-century artists, shows Latona, a protector of the nymphs and Jupiter’s lover, after she has given birth to twins Apollo and Diana. She has escaped to the island of Delos in fear of Juno’s jealousy. Scultori’s signature can be seen on the bottom left hand corner, which she included to emphasize the legal status of her work, along with a further inscription on the bottom right.

[1] Evelyn Lincoln, ‘Making a Good Impression: Diana Mantuana’s Printmaking Career’, Renaissance Quarterly, 50, no. 4 (1997), 1102.

[2] Lincoln, 1102.

[3] Lincoln, 1106, 1111.

[4] Quoted in Lincoln, 1105.

[5] Italian Women Artists: from Renaissance to Baroque, 16 March–15 July, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington D.C. (Italy: Skira Editore S.p.A, 2007), p. 126.

[6] Lincoln, 1118.

[7] Italian Women Artists, 132.

Categories

- Uncategorised

- Prints

Leave a Reply