Secrets and Signatures

Rebekah J. Harris – PhD Candidate in History at the University of Melbourne School of Culture and Communications

The most alluring aspect of an archival family collection is its honesty – its documentation of a family’s success and failures. Unless someone has deliberately removed something, personal papers hide very little. In this respect, the Bright Family Collection, recently catalogued by the University of Melbourne Archives, is particularly revealing. The collection is a rare record of 18th century British trade in the Caribbean, and it follows the Bright family’s business as plantation owners in Jamaica, the West Indies, for roughly four hundred years (1511-1974). As documents recording the disturbing history of slavery, they give crucial insight into the British Empire at its height. However, as a family collection, it holds thousands of letters, of commercial and private consequence.

Scholars of all periods regard letters as crucial to the historical understanding of cultures and people, but there is nothing more exposing than a familial letter. Having read only a fraction of these letters, it was clear to me that the Brights were not only know for their immense wealth, but were a widely respected and admirable bunch. In fact, many of their letters concerning the slaves on West Indian plantations were radically compassionate.[1]

But like all families, they had their issues. Through the papers of the Bright Collection, we can piece together the individuals, and indeed, individual tastes, of each family member. Take Allen Bright Snr., for instance, he was a pewterer for his Uncle, Henry Bright, in Jamaica. Notably, the name A. Bright appears alongside a notable increase in receipts for rum and ‘grapes,’ and other slightly decadent debts to tailors and builders. Although considering his profession, drinking was a suitable pastime to use his pewter utensils. What is far more telling about Allen, however, are the openly expressed opinions of his family. Take, for example, the frustrated letter from Bristol, East Sussex in 1750. Simultaneously charming and scathing, his younger sister informs him that his mother is deeply disappointed in him for not bringing his young wife home to see her, and: ‘…she takes it very uncind of you…She did not think that she should have ever lived to have askt anything of you that you wold have denied her…’

In the section of the letter below (figure 1), the handwriting brings her sentiments alive– as a staggered, chaotic and amazingly expressive letter from a frustrated girl. To be honest, holding the material letter made me terrified of the wrath of Allen’s mother and sister. The uneven lines, the scribbled out words and splodges heighten the emotion behind the letter. Evidently, Allen’s ‘loving sister’ was on an important errand in writing this hasty reprimand, before she sprinted back to the side of a mother whose nerves were wrecked, having: ‘not comedoun stairs yet, but have no other complaint but her cof which is much better my compliments…’

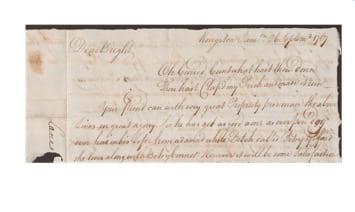

Yet, family misdeamers did not end here. And Allen Snr’s mistakes are not to be compared to his son’s, Allen Jnr. On September 26th, 1767, the younger Allen received a far more serious letter from a friend, known as ‘Lane.’ The letter’s beautiful handwriting; confident, cursive and suave, is a surprisingly accurate description of his personality, as understood from this shocking letter. The letter is triumphant, beginning with the lines: ‘Oh Cursed C*#!t what has’t thou done.’

Lane’s letter pronounces his successful seduction of a young Betsy Griffiths, the daughter of Capt. Griffiths from Boston. He writes of how they met and how the affair began… because, as he happily admits: ‘it will be some satisfaction to me to propagate it among a few Particulars…’

Not only does Lane reveal himself to be far more suave and conniving than his perfectly tidy hand, he also leaves us questioning the propriety of his friend, Allen. Of another young lady, he writes, ‘they tell me vows and protests that you never gave her anything… what must a person think of such an Eternall Createure.’ And he signs off, with a suitably contrived and flourished signature.

However morally repugnant, the father and son’s letters bring us in touch with the experiences, associations and social conventions of the mid-eighteenth century – their gossip, their illicit secrets, and their responsibilities. Although the Bright Family Collection yields incredible insight into the business and formal correspondence of prominent landowners of the 18th and 19th century, the familial and social relations are equally as enlightening for the historian. Allen Snr. And Allen Jnr. Bright’s papers are just a scratch on the surface of the vast amount of intimate affairs to be discovered amid the Bright Family’s correspondence across the Atlantic.

Rebekah Harris is a PhD Candidate in History at the University of Melbourne School of Culture and Communications. Her thesis investigates the private and public communication methods of social reform for Victorian feminists, and in particular, the Kensington Society (1865-68).

Note: The handwriting of the original archives can be difficult to read, and my translation, while attempting to replicate the spelling, is not necessarily accurate.

[1] Kenneth Morgan, ‘The Bright Family Papers,’ Periodicals Archive Online, Vol. 22, Iss. 97, (1997), 126.

Leave a Reply