‘Dear Householder’

Anton Donohoe-Marques

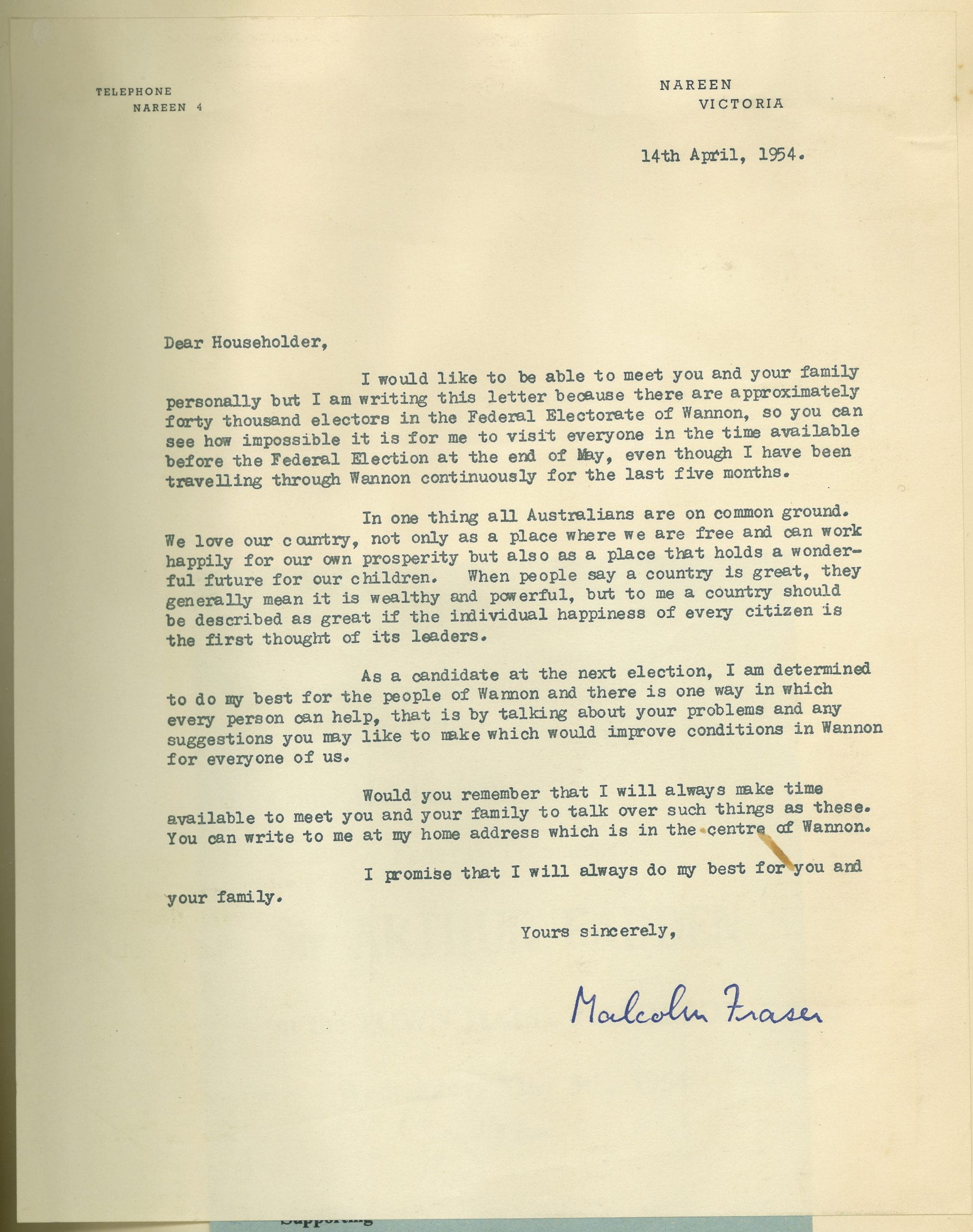

‘Dear Householder,’ begins this intriguing letter from former Liberal Party Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser’s first political campaign for the electorate of Wannon, in 1954. The signature, indelibly marked in blue pen at bottom of the letter, evokes an image of a young and passionate Fraser sitting at his desk, hand aching, signing letters repeatedly to be delivered around the electorate of Wannon. This personalised style of political engagement is a far cry from present-day political leaflet drops, printed by the thousands and deposited in letterboxes by crews of political canvassers. The bespoke nature of the letter is also emphasised by the typed text, sometimes wonky and yet carefully formatted, which hints at the typist, perhaps Fraser himself or a friend or a relative, working tirelessly over a typewriter to produce copy after copy for the campaign.

The document itself comes from one of Una’s carefully compiled scrapbooks. In the latter years of her life Una attended lectures at Melbourne University, taking a strong interest in history and art history. Given her love of the historical landscape then, it is unsurprising that she understood the value of archived documents for future generations of historians and history students (as well as any other potentially interested parties). In this context, the letter, along with the other ephemera contained within these scrapbooks, are imbued with a duality that straddles the line between private and public. They illustrate a mother’s pride and care for her son’s achievements, as well as an understanding of the historical value of archival artefacts.

Historically, I was intrigued by this particular letter which embodies the idealism that drove Fraser in his early political life. Notorious for his role as caretaker prime minister following the Whitlam dismissal, at this period Fraser was an unknown quantity in the Australian political sphere. This letter to the ‘Householder’ begins however to demonstrate Fraser’s passion for the political philosophy of liberalism, fostered during his time at Oxford University, from where he had graduated two years earlier.1

The issues Fraser identifies bear a distinctly individualist and egalitarian tone. He implores his readers that “a country should be described as great if the individual happiness of every citizen is the first thought of its leaders.”2 He further advises the importance of this notion for the future of the country in his statement that Australians love their nation “not only a place where we are free and can work happily for our own prosperity but also as a place that holds a wonderful future for our children.”3 Fraser’s emphasis on egalitarianism and self-determination is consistent both with his own rural upbringing and with the ‘bushman ethos’ identified by Russell Ward as a foundational part of the Australian national character. This ‘bushman ethos’ describes a distinctly Australian national character marked by irreverence, egalitarianism and a rugged style of masculine individualism.4 In the context of Fraser’s eventual rise to the highest office in Australian politics, this early example of engagement with his voting bloc is a modest illustration of the values and rhetoric that would come to define his political career.

Anton’s thesis examines the changing shape of remembrance practices that centre upon the Second World War in Australia. It examines how these practices have shifted in response to political and cultural changes in Australian society over a number of contexts.

1 Philip Ayres, Malcolm Fraser: a biography (William Heinemann Australia, 1987), 53.

2 Malcolm Fraser, “Letter to Wannon Constituents,” Letter, April 14, 1954, Una Fraser collection, University of Melbourne Archives, 2008.0058 unit 2.

3 Ibid.

4 Russel Ward, The Australian Legend (Oxford University Press, 1965), 2.

Leave a Reply