Narrating Photography

Alice Helme

A picture says a thousand words. We all know that ubiquitous and often overused phrase. It is the cornerstone of art analysis and an art historical approach to dissecting pictorial representations. An image presents a visual narrative, conveying a story or meaning through the silent channels of sight. These narratives are fabled to tell a truth, an unaltered vision of the artists’ projected thoughts, or convey a reality of time and place. Photographs have always been revered as a mode of truth telling, as opposed to paintings and other figurative art forms that are imagined from the mind of the artist. Their image captures a moment, and in that scene of suspended time the photographer presents exactly what they saw. We are presented with the perspective of the photographer, or their directed framing of a scene. The image speaks for itself, to use another popular idiom. But what happens when alongside the photograph or series of photographs there are captions and a specific order, all of which were placed and curated by the photographer themselves? Does the meaning alter? And if so, does it reveal a kind of commentary by the photographer? Is this added information then lost in the processes of digitisation and online viewing?

In Una Porter’s photographic albums, not only do the photographs themselves tell a story of her journey and activities, but the curated sequence of images and the handwritten labels showcase a meditated process of selection and descriptive observation.

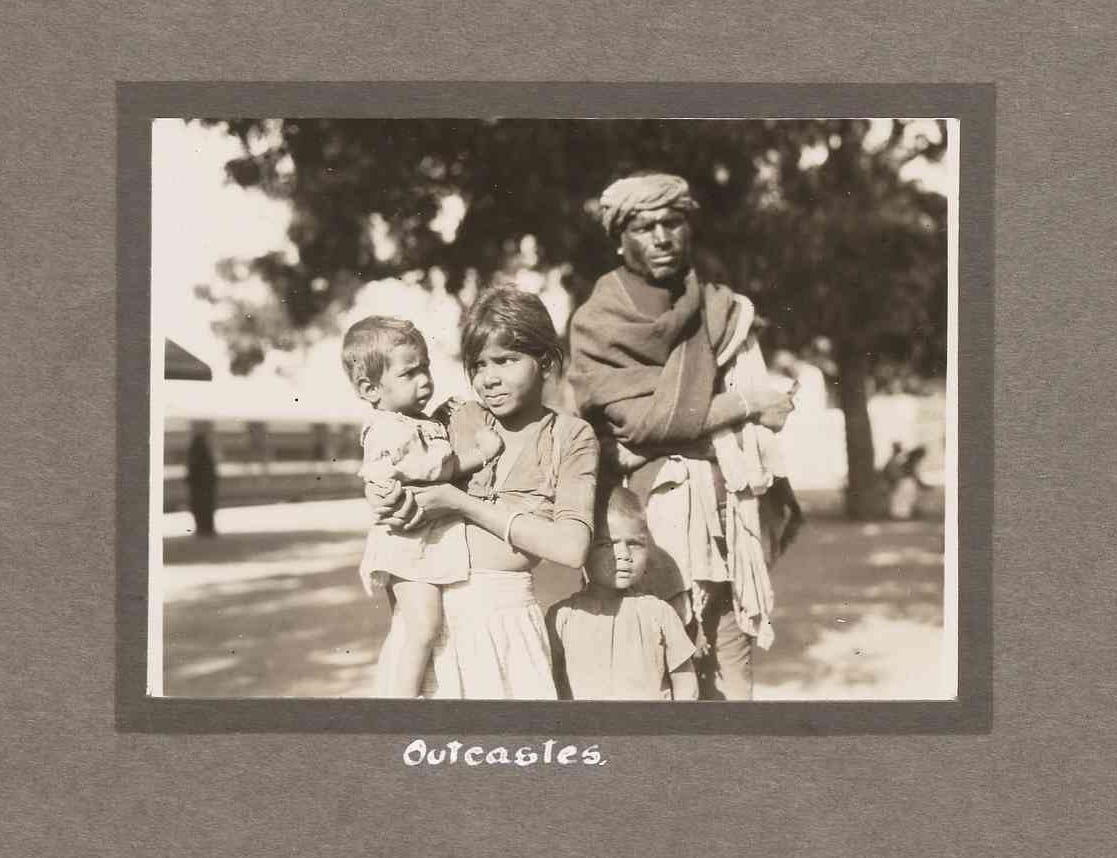

Under each framed image is handwritten text, describing or labelling the photograph. In one of Porter’s albums there are two photographs which exemplify the importance of labels and the commentary that they imply. Separately and unlabelled these photographs show an interest of the photographer in in aspects of life in India; however, in combination with the juxtaposed placement in relation to one another and their captions, these photographs reveal an interesting social commentary.

The first presents a family, assumed to be local to the area, of a father with his three children. The adult male figure stands behind the children with arms crossed and swathed in fabric shawls and a cloth headdress. The children are clothed in noticeably shabby or old garments. One assumes that this is a family belonging to a lower socio-economic group; however, the caption below reads ‘Outcastes’. This word confirms the assumption of a lower status individual, but it also reveals Porter’s encounter with members of a low ‘caste’, which in the Indian tradition refers to a social hierarchy that is ethno-categorised. This label is not entirely ground-breaking in revealing information; however, as we view the photo placed diagonally to the upper right of the page the captions and photos hint at a commentary created by Porter.

The second image presents a very different scene, albeit within the same geographical region. Located on a street lined with vendors, two holy figures sit with knees drawn to the chest on boards of nails demonstrating their tolerance and prowess over earthly pain. Both are male, while one is an adult with long hair and full beard, the other appears to be a child or youth. They are dressed in modesty cloths only, but openly acknowledge their surroundings with the adult raising his hand in answer to an unseen person out of camera-shot and the youth looking directly into the lens. The caption Una Porter chose to write below was ‘Ascetics’. The term implies a self-humbling of an individual’s physical body to a life of poverty to discover the higher powers of the mind and religion. The term once again informs us of an acknowledgement on Porter’s part of a way of life in India.

When placed alongside each other these terms form part of the photographer’s narrative in the album, and create a commentary on social structures from the perspective of a Western female missionary. Porter highlights the dichotomy of societally enforced ostracism and self-imposed asceticism. Her images create a study of two ‘types’ of social condition, and apply a Westernised typological narrative to the pictures. In this way, the meaning of the photographs alters from decontextualized visions of the past to, with the aid of captions and sequence, a clear statement of the photographer’s intentions and thought process. These details are, however, not materially a part of the photographs. They are additions contained within the structural assemblage for displaying the images. This presents an issue in the digitisation process, as creating a digital facsimile of the photograph alone removes these important details. We are then presented with how do you digitise such items for academics to access and use to their full potential. In the current world of limited digital storage and reduced archival personnel, digitising the entire album is inefficient and labour intensive. The question remains, how do items such as Una Porter’s albums make the transition to the digital world without removing such important and unique details?

Alice Helme is a PhD student in the School of Culture and Communication, researching the display and communication of devotional art in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence.

Leave a Reply