Priestley’s Penguins

Andrew Fuhrmann

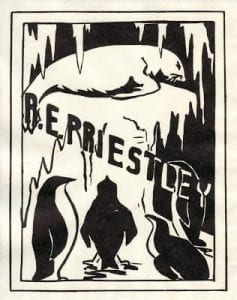

There’s no doubt that Raymond Priestly (1886-1974) had a fondness for penguins. Open any of the fourteen volumes of his Australian diaries (1935-1938) and there they are on the inside cover. The personal bookplate of the eminent geologist and Antarctic explorer depicts an icy scene in bold black and white with a fur seal surrounded by four rather stout penguins.

In fact, his diaries are populous with penguins. During his time in Australia as Vice Chancellor he gave many public talks about penguins and went on a number of penguin-watching expeditions. Priestley even made a point of recording his conversations about penguins, including this one with Sir James Barrett (1862–1945), his predecessor as Vice-Chancellor (1931-1934):

“Sir James told me of penguins at Gabo Island that climbed steep rocky slopes 300 feet to make their rookeries, and I was of course able to cap the tale with 500 feet to spare from my Cape Adare experience, and also clinch the matter by explaining how we had found seals on the Ferrar Glacier 40 miles from the sea and 4000 feet above sea level. The penguins here are called Faery penguins and they and the Mutton Birds are among the recognized sights of the island.” (Entry for Wednesday 23 February 1935 in volume 1.)

He would later describe the large and rather shambling Sir James as having the aspect of an Emperor penguin. (See entry for Thursday 11 July 1935 in volume 3.) Sir James was appointed Chancellor in 1935 and was embroiled in a protracted struggle with Priestley for executive control of the University, a conflict that contributed to Priestley’s decision to resign in 1938.

In some ways it’s remarkable that Priestley could still stand the sight of these all-but-featherless friends. On both his early voyages to Antarctica, on Shackleton’s ‘Nimrod’ Expedition (1907-1909) and Robert Scott’s ill-fated ‘Terra Nova’ Expedition (1910-1913), penguins were regarded as a food source as well an object of scientific interest. Indeed, on Scott’s expedition, Priestley was one of a six-man group forced to shelter for seven months in an ice cave at Terra Nova Bay, during which time they lived almost exclusively on seal and penguin meat.

Mike Bullock, author of Priestley’s Progress: The Life of Sir Raymond Priestley, suggests that seals were probably the group’s staple diet while penguins would have been something of a luxury. Perhaps that’s why the fur seal in the icy cave illustrated in Priestley’s bookplate looks so sourly saturnine!

Priestley’s encounters with penguins were a great highlight of the public lectures on polar exploration he gave in Melbourne and throughout regional Victoria. (In the entry for Tuesday 18 June 1935 he worries that an audience at the Brighton Town Hall will find his lecture dull because he has “eliminated the penguins entirely”.) These lectures were illustrated with Priestley’s extensive collection of magic lantern slides – an early kind of glass-plate slide that creates a 3D effect when projected onto a screen. The Department of Geology Collection in the University of Melbourne Archives has a set of 1339 glass-plate negatives used by Priestley in these Australian lectures. And of course there are plenty of penguins.

The bookplate itself is striking but unsigned, unusual for an ex-libris woodcut. Could it have been designed and executed by Priestley himself? He was a fair draftsman with a scientist’s eye for detail. Although the penguins are stylised, they are clearly identifiable as Adélie penguins: sturdy birds with stubby beaks and no crest. At the very end of his Australian diaries, however, the true artist is revealed. The entry for 2 September 1938 reads:

“In the afternoon I wrote to Bert and then Tudor and I walked in to town where I left my films to be developed, collected a very nice bookplate indeed, which Jocelyn has made for me as a birthday present”. (See volume 12 of the diaries.)

Jocelyn Fleming née Priestley was his eldest daughter. Born in 1916, she married an Australian engineer and settled in Melbourne after her parents returned to England in 1938. She studied art and, according to an article in the social pages of The Bulletin in 1941, her woodcuts were “well known and commended”.

This is just one of a number of bookplates that can be found in the University of Melbourne Archives. There’s one by Australian artist and noted bookplate designer Adrian Feint for the late Malcolm Fraser. Fraser’s bookplate can be viewed in the Archive’s digitised collection. Bookplates or ex-libris do more than indicate ownership; they also reflect on the character or interests of the book’s owner. Fraser’s bookplate, for example, is crowded with significant items, including references to his love of sport and his upbringing on a sheep station.

What might Raymond Priestley’s bookplate tell us about the first salaried Vice-Chancellor of the University of Melbourne? Well, he was in his early twenties when he embarked on his first Antarctic expedition and no doubt penguins were a reminder of this formative experience. But could they also have signified courage or determination or some other quality he discovered within himself on those difficult polar journeys? Could they have acquired totemic importance?

Or was he simply charmed by these characterful creatures who seem so much at home in the most hostile environments?

Andrew Fuhrmann is a PhD candidate in the School of Cultural and Communications and a Research Assistant for AusStage LIEF17, in the Digital Studio. His research interests include digital collections for the performing arts, poetics and contemporary dance and performance analysis. He has a master’s degree in theatre studies from the University of Melbourne and teaches research methodologies and critical thinking at the Faculty of Fine Arts and Music, also at the University of Melbourne.

Leave a Reply