William Kennedy Laurie Dickson- A Legacy of the Moving Image

Emma Hyde

William Kennedy Laurie Dickson was born in 1860 to Scottish parents and began his career in America as an assistant to the inventor and businessman Thomas Edison. Both were key figures in the experimentation of the first commercially successful moving image apparatus: the Kinetoscope (a viewer) and the Kinetograph (a camera). First known as the Edison format, Dickson’s lasting contribution to cinema history is undoubtably the 35mm film gauge[1]. Devised in 1891 and used for cinema projection throughout the 20th Century it is still in use today. UMA holds three early 35mm film samples which highlight the important role Dickson played in the evolution of moving image technology. Their rediscovery amongst family papers illustrate his desire for both professional and personal recognition, and reveal the methods he employed to safeguard his legacy with both film historians and his relatives in Australia.

W.K. Laurie Dickson had a half brother, Raynes Waite Dickson, a lawyer who migrated to Australia and settled in Melbourne. Raynes Waite had a son, Raynes Waite Stanley Dickson who was the recipient of a number of letters written by W.K. Laurie Dickson. A couple of these letters reside at University of Melbourne Archives, the contents of which discuss family matters and financial hardships suffered by W.K. Laurie Dickson in his later years. However, one of the letters written by W.K. Laurie Dickson in March 1932 reveals a number of interesting contents. Composed on writing paper ‘From the Laboratory of W Kennedy Laurie Dickson: with Edison 1881-1897’ the letter contains three 35mm film samples and a PostScript by Dickson inscribed around the sides and bottom of the letter stating:

‘I see in many papers and journals I am, since the deaths of Edison and Eastman- given credit for my pioneer work at Edison’s – in producing the 1st film/present day cinema film- as per souvenir samples for your albums’.

Dickson sent similar samples to a number of people, including journalists and historians, but the UMA finds are a rare example of Dickson sending samples to a relative. Dickson’s letter to Raynes Waite Stanley was written several months after the death of Edison (1931) and this event, along with financial insecurities facing Dickson at the time, must have impacted on his general outlook on life. The fact he was writing on old laboratory paper to a relative and referencing film samples as an afterthought, indicates Dickson may well have been cementing his own legacy in his final years.

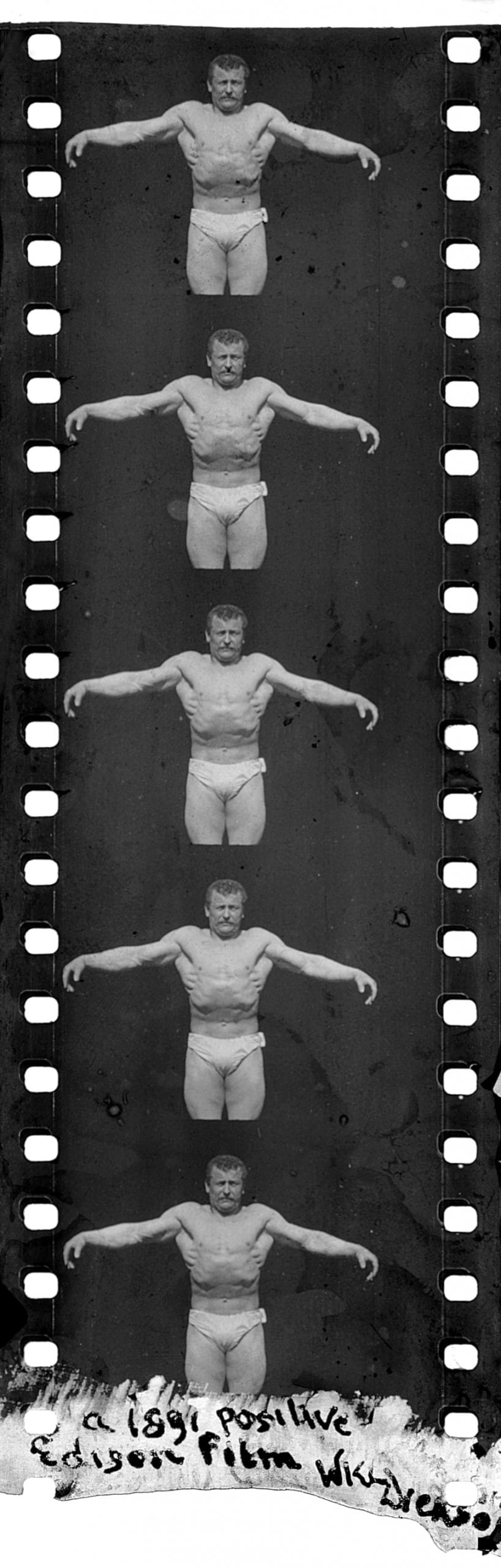

The first of these samples is a five frame sprocketed film strip featuring Eugen Sandow, known as the ‘father of modern bodybuilding’ flexing his muscles. Sandow (Freidrich Muller) was filmed by Dickson for Edison in the Black Maria Studio[2] on 6th March 1894. The bodybuilder was a feature of the first exhibition of Edison’s peep show Kinetoscope and the filming of Sandow can be regarded as the first commercial motion picture production’.[3] Dickson has included a notable inscription at the bottom of the strip claiming ‘a 1891 positive Edison film. WKL Dickson’. This strip is known as [Sandow No.1] and was in fact produced in 1894 and not 1891. Dickson deliberately pre-dated the film strip and it appears such a practice was a regular occurrence for him.

Dickson tried to move the dates in the mistaken hope this would establish Edison (and himself) as the first to make movies. Film Historian Paul Spehr mentions Dickson frequently pre-dated his work and was doing this so frequently he may have come to believe his own misdating was in fact accurate.[4] Dickson was not unique in this practice and USA copyright law may have been a major factor in deliberately pre-dating work, as it required that an application be reviewed by a patent specialist, which could be challenging in terms of establishing when prior work/art was created.[5]

The second set of samples found in the letter are two copies of positive film (three frames) showing a blacksmith scene. The two samples are known as ‘Horse Shoeing’ and this film was a significant test for Dickson of the ability to make films.[6] This scene was one of the first films to be made in the Black Maria Studio. One copy is inscribed as ‘Hand on Horse, May 1889. Edison’s Lab. First Successful Edison Film’. Dickson has noted on the reverse: ‘2 scraps of original films of 1889 (May)…unfortunately the perforations were trimmed’. On the reverse of the second sample Dickson writes: ‘Ditto- 2nd scrap- these scraps being all there is in existence since the Edison film fire many years ago- makes this sample/s most valuable. W.K. Laurie Dickson’

Dickson also sent a very similar sample to Eastman’s Oscar Solbert[7] in 1932, around the same time he sent these samples to Raynes Waite Stanley. Both samples give misleading dates of 1889. In fact the film was shot in either early April or early May of 1893 and is another example of Dickson exaggerating the truth. Even though his misrepresentations of chronology have perplexed many film historians over the years, these two film fragments are almost certainly the earliest known examples of 35mm film to exist in Australia. While they are not unique or shot in Australia, they are valuable artefacts in UMA’s audiovisual collection. This rediscovery illustrates the fascinating personality of W.K.L Dickson, who made many claims to secure his place in film history. Not only was he a significant inventor, but was also an anonymous performer in the Horse Shoeing film (although he does not feature in these film samples) and can therefore be credited as the first movie director to be appear in his own film.[8]

Emma Hyde is the Audiovisual Archivist at the University of Melbourne Archives.

Many thanks to Paul Spehr for his invaluable knowledge and advice.

[1] Spehr, PC 2008, The man who made movies : W.K.L. Dickson, John Libbey, Eastleigh, p.239/386

[2] Thomas Edison‘s movie production studio in West Orange, New Jersey. Known as America’s first film studio

[3] Ibid., p.327

[4] Paul Spehr email correspondence

[5] Paul Spehr email correspondence

[6] Paul Spehr email correspondence

[7] Solbert was the first Director of George Eastman House. The World’s first museum and archive dedicated to photography and the motion picture

[8] Ibid., p.330

Fine article, Emma Hyde!

I have Raynes Waite Stanley Dickson’s admission certificate for his admission to the Victorian Bar. If a family member is out there, It’s looking for a home.

Please contact Tanis Dickson daughter of Raynes Dickson